Posted in

Film & TV,

Posted in

Film & TV,

Airtime is building a global cinema scene for people who actually feel things

Text Maya Kotomori

You wouldn’t steal a car. You wouldn’t steal a handbag. You wouldn’t steal a television. You wouldn’t steal a DVD. Downloading pirated films is stealing. Stealing is against the law. Piracy. It’s a crime.

One could argue that the most successful curators are pirates; look at 90% of museums in the Western world whose work is largely comprised of the spoils of war, colonial missions in countries still affected to this day, and the like. Turkish filmmaker and curator Aslı Baykal is a pirate herself, except she’s one of the good guys. Over the years, Baykal has become a vital figure in New York’s independent film scene, curating programs that foreground overlooked global cinema and subversive film histories. She has directed music videos for the likes of Sampha and Karen O, as well as her own films, one of which, called Darkroom, was featured in the 2023 MoMA Doc Fortnight screenings.

Her project, Airtime—an underground in-person screening series and an online platform—isn’t about exclusivity or ownership. It’s about sparking real human connection through the moving image. From hunting bootleg DVDs in Turkey or streaming movies ripped from Limewire, Baykal seeks to use Airtime as an extension of her childhood discovery of film from her bedroom, today hosting live screenings in synagogues and parks to airing films online that, as the project title suggests, deserve airtime. Since its inception in 2018, Airtime has hosted screenings in collaboration with institutions such as eflux and filmmakers like Bette Gordon and even has a website where viewers can stream films directly. Currently on view at airtime.world is the Nollywood cult classic Blood Money (1997) by Nigerian director Chico Ejiro, as part of Baykal’s longstanding collaboration with Nolly Babes, a fellow screening series dedicated to celebrating Nollywood films.

I asked Baykal how she sourced Blood Money, and she told me that Nolly Babes has its own Nollywood archive that they’re building. To me, people like them and Baykal are the real pirates, young curators seeking agency over the films from their upbringings outside the West. They’re the good guy pirates because they want to expose people to all the films they might be looking past in fear of feeling something.

Dazed MENA sat down with Baykal to talk about childhood obsessions, resisting film school pretension, and what it means to make screenings feel like a community, not content.

What was your upbringing like?

I grew up in Istanbul. I spent my summers at my parents’ hotel in a seaside resort town in southern Turkey. That’s where many of my storytelling sensibilities and observational qualities come from. It was almost like a utopic circus with many characters, family dynamics playing out, and tourists from around the world. And I was a young girl coming of age in the middle of it.

And then, after high school, you made it to Tisch!

I studied undergrad film at NYU with a focus on directing and producing. Sometimes, I feel self-conscious around people who did cinema studies and are more eloquent about a hundred obscure directors because I have more of an emotional relationship to film. I can probably name 100 too, but I’m more like, ‘Let’s try this and see if it works.’

I relate. I studied film theory in grad school, and it felt like everyone knew every detail about Fellini but couldn’t tell you why 8½ made them cry.

Exactly. Film school was full of dudes who talked about how PTA dropped out and thought it was so punk. They were so dismissive of women—it was exhausting. I obviously learned a great deal and am grateful for my experience. Through these people, I was able to understand that real creativity happens when you admit you don’t know everything and chase that curiosity.

Which is exactly how Airtime feels.

Thank you. I grew up an only child, so cinema was a solace and an escape. My dad also felt similarly about films, so it was a connection we had. Sometimes, it feels like I am pursuing this field to honour him and his hidden talents. I’d watch three films a day, either DVDs from the bootleg guy or Limewire downloads that took a week to access. One DVD box might have Kurosawa, Alien, and Iranian cinema all in one. It was chaotic and perfect.

That collection is its own film education.

It made me want to create something where a teenager anywhere could stumble upon work that feels meaningful and impactful. The internet promises everything is one click away, but discovery still needs curation. That’s what Airtime is about. I want people to feel the same way about finding a new film as I did when I was 15, watching movies alone in my bedroom from my laptop. And I get to collaborate with filmmakers and thinkers I admire through a path I’ve created.

When did Airtime officially begin?

I graduated [film school] in 2011, and then my dad got sick. I was directing some music videos and helping friends with their productions, but the idea for Airtime came in 2018. Social media was peaking, and I saw amazing filmmakers being overlooked in favour of brand-friendly types. I wanted to showcase the work that I felt was the most impactful.

And the first screening?

Seward Park, 2018. My mom made Turkish meatballs. The inflatable screen deflated mid-film, and friends literally rushed over to hold it up. It was hot, chaotic, and beautiful. My dad was there. That meant everything. It wasn’t polished, but it was real. The things that didn’t work out didn’t work out for a reason, but they made me see what Airtime actually is. There is no press release and no real promo aside from word of mouth. Just food served family-style, films, and people.

What came next?

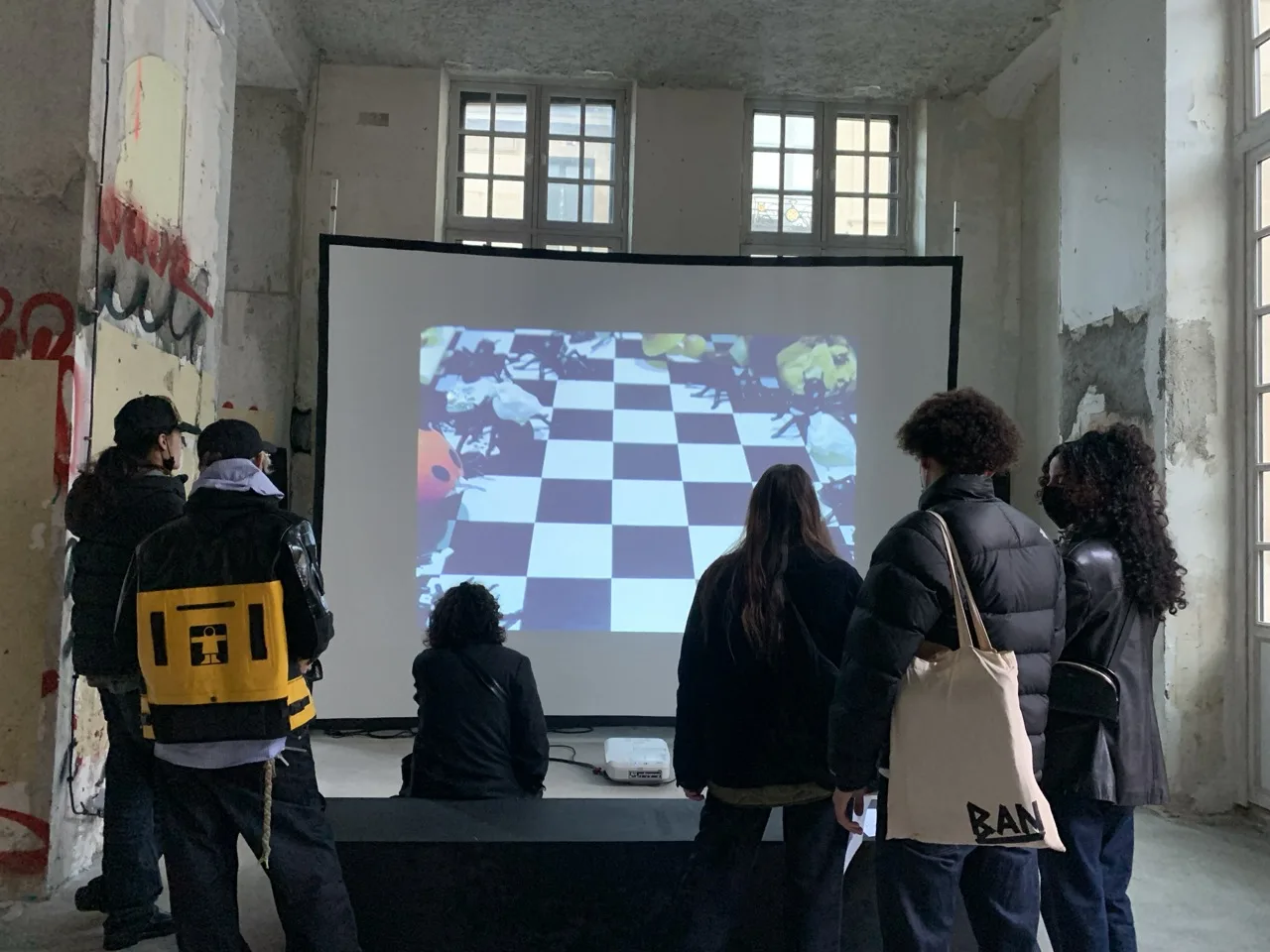

We conducted a second Seward screening, followed by East River Park, in 2021. In 2022, a big one in France co-organised with my close friend Ben Broome at Dover Street Market Paris. By then, I’d built a rhythm. But I didn’t want it to feel like an ‘event series’; I wanted it to feel like an experience. I created the Airtime website in 2023 to continue curation online.

I grew up as such a fan of things, and it was so important for me to have access to music, film, and art, so that’s what Airtime Online is. I made the website right after the East River screening, which I put together in four days. I loved the rush and excitement from that experience, but I also realised that I didn’t want to wait for another evening to share films; I wanted them to be able to watch online, not just sharing these films in an NYC bubble but making them accessible anywhere. It gives me the power to be more consistent and also share films I love with people so they can watch them in the same way I would watch a movie in my room as a teen.

It’s funny because people always compliment the site and how easy it’s to navigate; it’s just one page with the film available to watch, and that’s it. There’s only one page because I couldn’t afford to pay a designer to make it more interactive! People always tell me that they love that as an aesthetic choice, and honestly, I like it, too. Simple.

What kind of work do you look for to put online or for a live screening?

Something that pushes form and feels emotionally textured. I’m drawn to films that blur lines, narrative through documentary, or vice versa. That overlap is where the magic is. I find that inspirational for my own work as well. It makes me look at subjects and forms in a different way. I tend to lean towards those films. Archival gems are very important to me, as well. Coming from where I’m from puts me in a special position, a place where you have access to both sides of the world and various cultures in one city. There is an urgency in me to highlight ideas and voices that are impactful in today’s timeline of events.

You’ve mentioned to me before that you didn’t like documentaries in school, but now that’s mostly what you make. What changed?

I almost failed a doc class at Tisch and said, ‘I hate docs; I don’t think I ever want to do one.’ Educating myself through obscure works, I’ve seen in microcinemas in NY and coming across stories I want to document in Turkey. I realised there are no rules to how you can make something. You don’t have to wait for permission. You can feel the shift when you watch someone like [Abbas] Kiarostami. He started making educational videos for kids. Then, his work continued into these humanist, existential films. That balance blows my mind. To question what life is across a range of audiences opens doors in my head.

Also, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, I’m a big fan. For some reason, whenever I think about him, I think about sleep. In his movies, he wants you to have that. In Memoria, I just couldn’t keep my eyes open. It’s like a mixture of sound, visuals, pace, and rhythm. He is in charge; he’s like a magician.

While I see and respect that movie, I think I’m a little bit too American for it in that I like to be entertained by movies more than anything.

Memoria is a whole-body experience. I don’t think it’s a film you can watch over and over again; it’s like memory. I also read an interview by him where he talks about censorship in Thailand, which I also witness within Turkey. He is so poetic about politics and the myths of these places that I really look up to him in creating poetic storytelling.

Do you want to do more physical screenings?

Definitely, but I want each one to feel special. After the Paris screening, I realised I actually enjoy doing this—and I’m kind of good at it. I’ve also collaborated with Union Docs and eflux, and did a screening with a live score by Coby Sey at Young Space in London. I like locations that feel unexpected and push the idea of how a screening should be structured. Community gets thrown around as a buzzword, but I really mean it. My friends bring beer. My mom used to cook. Everyone chips in.

I would love for Airtime to keep growing globally. I want to have more international screenings —especially one in Turkey, for obvious reasons. I imagine one in an ancient amphitheatre by the Mediterranean coast. I also want to create small publications rooted in research, whether focused on specific directors or evolving from conversations.

Basically, my goal is to continue creating unique cinema experiences in unexpected venues—and to keep experimenting with what those experiences can be.

My next screening idea is to host one inside a drained pool. But we’ll see! [Laughs]

There’s this great quote by fashion critic Lynne Yaeger where she says that the best advice for people wanting to get into fashion is to study everything else that isn’t fashion. I’m curious, for film: what would you say are the best things to study outside of film that will help you understand film?

I read a quote by Agnès Varda recently. She said: “Nothing is dull if you film people with empathy and love. Nothing happens, yet something happens inside.” That’s it. You don’t get that from a book. You get it from watching, listening, and feeling. From studying life, not just cinema.

To explore Aslı Baykal’s programming, visit Airtime.World

Follow @airtime.world on Instagram for updates on future screenings.