Posted in

Magazine, Arab Publishing

Posted in

Magazine, Arab Publishing

Maya Moumne in conversation: design, authorship, and Al Hayya

Text Marie Saadeh

Graphic design is often sidelined to a supporting role, but Maya Moumne insists on its place in the driver’s seat as an agent of discourse. Her body of work attests to this; the Lebanese graphic designer and publisher has been shaping the Arab design scene since she co-founded the Beirut and Montreal-based Studio Safar in 2012 alongside Hatem Imam. Noting the lack of critical works on Arab visual culture, the duo co-created Journal Safar to gather exchange in an annual print magazine. Several years later, she co-founded Al Hayya Magazine, a platform for exploration on anti-racist, transnational, and queer thought in the region, with photographer Myriam Boulos. Both magazines are distributed globally and printed in Arabic and English, with the languages distinctively intermixed throughout each copy. Especially amid the ongoing genocide against Palestinians and mounting censorship, the pages of every issue are bound by a call to challenge and to resist.

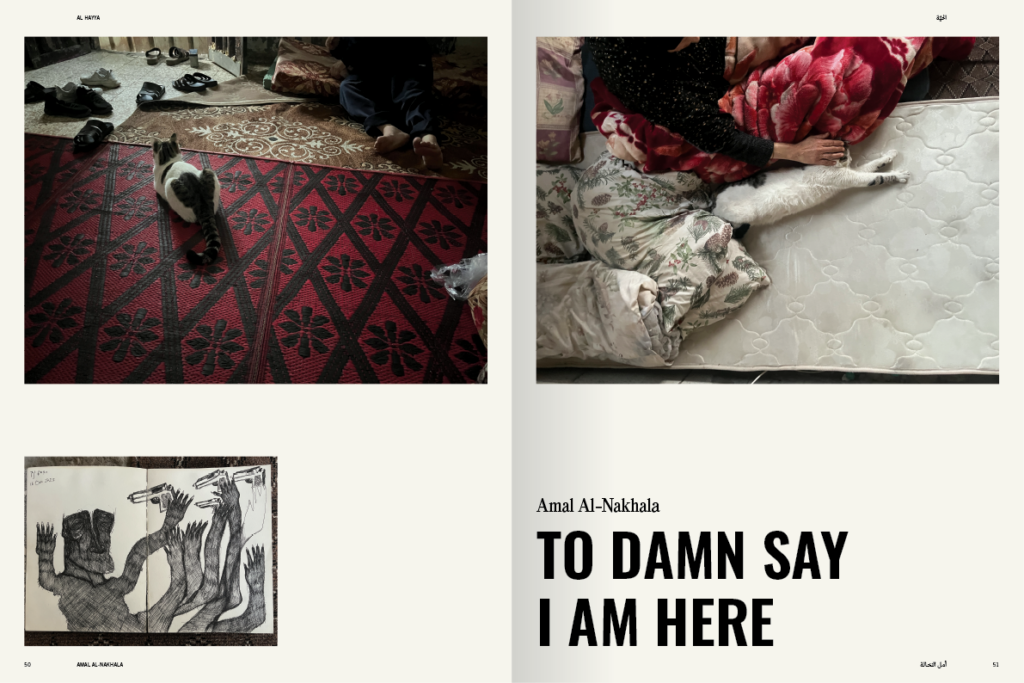

Issue #4 of Al Hayya, titled “Dreams of Liberation” and launched on April 18, includes a rare interview with the Palestinian revolutionary Leila Khaled and invites readers to consider moments of personal and collective resistance. Ahead of the issue’s Montreal launch, Moumne spoke with Dazed MENA on agency, archive building, and publishing about Palestine.

When in your life or career did you realize the potential of the designer as an agent of not just cultural production, but social change?

The design school I attended offered a course called Design in the Community, and another on the history of graphic design, which included a focus on the Arab region. Looking back, I think the trajectory of my career has been a kind of marriage between those two courses, which were, unsurprisingly, my favorites. That’s when I first began to understand the potential of the designer as someone who could contribute to social change.

When I first started design school, I didn’t fully grasp the depth or scope of the industry. But as I discovered what I could do (and just as importantly, what I couldn’t) I found myself trying to push harder toward that intersection of design and impact.

How has your attitude towards resistance through art and visual activism evolved since the escalation of the genocide?

I’m not currently in an optimistic place, personally or professionally, where I fully believe in the idea of resistance through graphic design. What I can speak to is design’s ability to democratize information. Graphic design can make complex or politically charged ideas more accessible to the public, ideas that are often dismissed as too difficult to grasp or too sensitive to engage with. That, in itself, can be a quiet form of resistance.

Journal Safar was created “to remedy the scarcity of critical writings on design in the Global South.” Can you speak a bit on what inspired Al Hayya and the different spheres each magazine occupies?

First, I don’t think Safar is addressing the scarcity alone; it’s part of a broader movement of initiatives reclaiming critical space for design discourse in and from the global majority. What’s significant about this moment is that more designers are recognizing their right to write and publish, just as much as to design. This matters because, within the hierarchy of design disciplines, graphic design is often relegated to the bottom and rarely afforded real agency.

Mohieddine Ellabbad’s Nathar series, published in the 1980s, stands as both an inspiration and a powerful precedent for what’s happening today. Not unlike John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, Nathar opens up critical conversations around visuality, often using popular culture as a point of entry. Ellabbad uses the word “nathar,” likely drawn from Bechara El Khoury’s verse, made famous by Mohammed Abdelwahab’s song “Gafnuhu,” as the title of this remarkable series. That verse proposes a fundamental link between vision and deep desire.

More designers today are documenting the history of Arabic graphic design while also documenting its contemporary practice. This growing body of work is helping reshape how design is valued both culturally and politically.

Part of my work on Journal Safar led me to realize just how much agency I could claim over what I produce, and where it goes. I came to understand that with the right team, I could publish anything. And that as a graphic designer, I could certainly shape how things looked, but more importantly, I could shape how content is received, where it circulates, and who engages with it.

Journal Safar fulfilled a very specific need I had as a designer: “to address the scarcity of critical writing on design from the Global South”. But it wasn’t speaking to another reality I was living. I am a woman, a business owner, [I] was living in Beirut, navigating everyday bias from clients, collaborators, and suppliers, often in male-dominated environments. At the same time, I realized that despite a lifelong obsession with magazines, I didn’t see myself represented in any of them. I knew little about the struggles and the feminist histories of women across the Arab region and its diasporas. That gap became the starting point for Al Hayya.

In many ways, it has everything and nothing to do with my background in graphic design.

Al Hayya just launched its latest issue titled “Dreams of Liberation,” and it explores resistance in its many forms. The covers featuring Leila Khaled are incredible. Can you speak a bit on the significance of this issue and the featured conversation with her?

What I can say is that this is, without question, the most significant piece I have published in my editorial career, and likely the most significant I ever will. It took immense effort to bring into the world. Earning Leila Khaled’s trust, securing the piece’s place in the issue, and arranging the visit to her home were far from simple. Lina Khalid, the gifted and meticulous photographer who captured Leila’s portraits, handled every detail with care and professionalism.

This issue, and Leila’s contribution in particular, sparked intense debate and raised urgent questions amongst ourselves: How do we publish work on Palestine? How is it told? How is knowledge transmitted, and through what frameworks is it received? I’ve come to understand that this kind of work requires much more than navigating censorship or securing resources, and that it sometimes requires contending with a politics of optics. And as a designer, publisher, and collaborator, as someone tasked with building and sustaining the structures that make this work possible, I feel this pressure constantly. The responsibility to fund projects, pay contributors, and keep the ecosystem alive is unrelenting. And sometimes that entails navigating all this within a climate of scrutiny.

And still, I would not choose another path.

With the intensifying censorship of Palestinian and Arab voices in the States, how was it launching this issue in New York?

I won’t lie, I was a little scared. I was worried about crossing borders, and even more so for my business partner, Dorothy Chakra, who came all the way from Beirut. But more than the launch itself (which went beautifully, huge thanks to Nour Sabbagh and Storm Books), what weighed on me was the worry that this issue wouldn’t be picked up by bookstores around the world.

To my surprise, it’s being carried by more bookstores than I ever expected.

As Palestinians ask us to bear witness to their struggle, artists and culture workers have had to consider the effective means of drawing attention to the genocide, and the role that images and testimony shared to fast-paced social media feeds play in mobilization. Has this discourse shaped your work in publishing? How do you view the potential of print media to respond to this moment?

Profoundly. The discourse around bearing witness, and the urgency of how, where, and by whom images and testimony are shared, has come to define the ethics and urgency of our work. It has made us think carefully about the question of effectiveness: what images, what tone, what platforms really mobilize, and which ones risk numbing or fatiguing the audience.

Fast-paced media ecosystems tend to flatten complexity; they reward immediacy over depth, reaction over reflection. In contrast, publishing, particularly in print, can offer a slower, more intentional form of witnessing and creates space for context, for contradiction, and for history.

That’s not to say speed isn’t sometimes necessary. But I’ve grown increasingly wary of the performative aspects of visibility. I’m more interested in building an archive that will last.

How have you seen the Arab publishing and media landscape—and more specifically, your audiences—evolve in recent years?

One thing is for sure: there’s been a visible and encouraging rise in publishing initiatives across the region in recent years, from Isdar Mustaqel in Cairo to Makan in Tangier. The landscape feels more interconnected and intentional than it did even a decade ago.

In parallel, the audiences for Al Hayya and Safar have grown and diversified. With each issue, we’re increasingly aware of who’s reading—not just geographically, but also politically and generationally. That awareness absolutely informs our curation and design. I’m feeling like it’s less about tailoring content to perceived expectations, and more about recognizing the responsibility of holding space for complexity and of making sure the design and tone supports nuance, and that the editorial reflects the evolving tensions and solidarities within and beyond the region.

You recently announced that Studio Safar is forming a publishing department. What inspired this expansion, and why is this the right time?

To be honest, this expansion feels less like a strategic move and more like a long-overdue step. For years, we’ve been thinking through the role of the designer not just as a service provider, but as a cultural producer, someone with the tools and responsibility to shape discourse, to archive, to challenge, and to imagine. Launching a publishing department is a way for us to formalize something that’s already been deeply embedded in our work on Safar magazine, which is the desire to engage critically with design histories, archives, and printed matter on our own terms.

It’s also a response to a need we’ve felt in the region for more collaboration between design studios, and more shared publishing efforts that push against dominant narratives.

Our first publishing venture is a collaboration with Camil Karam of Ya Hala Studio, focused on a body of work we’ve both been obsessed with for years, Palestinian resistance illustrations from the 1940s to the 1980s. We’re developing a series of volumes that function as both visual anthologies and critical readers, looking at these works not just as historical artifacts, but as active, resonant cultural tools. To make space for this new direction, we’ve decided to reduce the number of commissioned design projects we take on each year, and Safar magazine will continue uninterrupted.