Farah Pahlavi alongside Salvador Dalí at the inauguration of the House of Iran, Paris, 1967. Image courtesy of Assouline Publishing.

Posted in

Art & Photography, Farah Pahlavi

Farah Pahlavi alongside Salvador Dalí at the inauguration of the House of Iran, Paris, 1967. Image courtesy of Assouline Publishing.

Posted in

Art & Photography, Farah Pahlavi

Tehran has taste: the story of the MENA’s largest collection of modern art

Text Raïs Saleh

We’ve all seen the nostalgic posts on Instagram of Iran before the Islamic Revolution of 1979- featuring women with coiffed beehives and mini-skirts smoking cigarettes and dancing at the city’s nightlife hubs. Tehran in the 1970s was indeed a place of the hip and the glamorous- a cosmopolitan outpost of European university educated sculptors, artists, poets and princes. However, more profound than these flimsy posts attempting to paint a superficial retelling of the old Empire of Iran, is the story of the great collection of artists, art connoisseurs, literati and intelligentsia which made Iranian metropolises amongst the world’s great avant-garde cultural hubs. This group of bohemian creators were dedicated to creating a contemporary Iranian national arts scene, but in spite of the large numbers of Iranian artists at the time, they lacked a significant and central physical locus in which to exhibit their works of the abstract, the minimalist, the pop, or the conceptual- with the only real gallery spaces at the time being dedicated to classical Persian art.

So viscerally felt was the absence of exhibition spaces in Iran at the time that in a 1970 interview given to Ettela’at newspaper, esteemed Iranian artist Bahman Mohasses (fondly nicknamed the “Persian Picasso”) exasperatedly responded to a question about the presence of exhibition spaces in the country with, “That doesn’t exist at all. The gallery here is just a space where the painter is allowed or given permission to hang their works. There hasn’t even been a real gallery, and only two or three real galleries have now emerged. I mean, in the past—during the era of [Jalil] Ziapour [the “father of modern Iranian painting”] and others—there wasn’t even a place to present paintings, and exhibitions would be held in associations, and until recently, exhibitions were held in obscure places (such as the Export Bank).”

At the time, Iran’s oft-photographed empress, Farah Pahlavi, herself a student and lover of art and architecture, was on a political mission to empower the contemporary arts in the country. In so doing, she would embark on a number of extensive projects to put Iran on the international cultural map, including the creation in 1967 of the Shiraz Arts Festival, which was created with the intention of giving a meaningful public platform to emerging Iranian artists as well as internationally established cultural names. “One of my growing concerns in the second half of the sixties was not to forget culture in the march of progress,” writes Pahlavi in her memoirs. “On the one hand, we had to help our artists, improve their standing, and make them better known at home and abroad; on the other, we needed to open our borders to creative men and women from other countries.”

Yet the issue of a central and important permanent exhibition space remained. The dire situation for the country’s artistic establishment had to be remedied swiftly, and it would soon be done so with flamboyance after famed Iranian modern artist Iran Darroudi approached the fashionable empress at an exhibition expressing her wish and those of her artistic peers to have a place to permanently display works of Iranian contemporary artists. The art-conscious empress took kindly to the idea and immediately approached one of the greatest Iranian architects of the day, Kamran Diba, to go about designing a building which would become the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA).

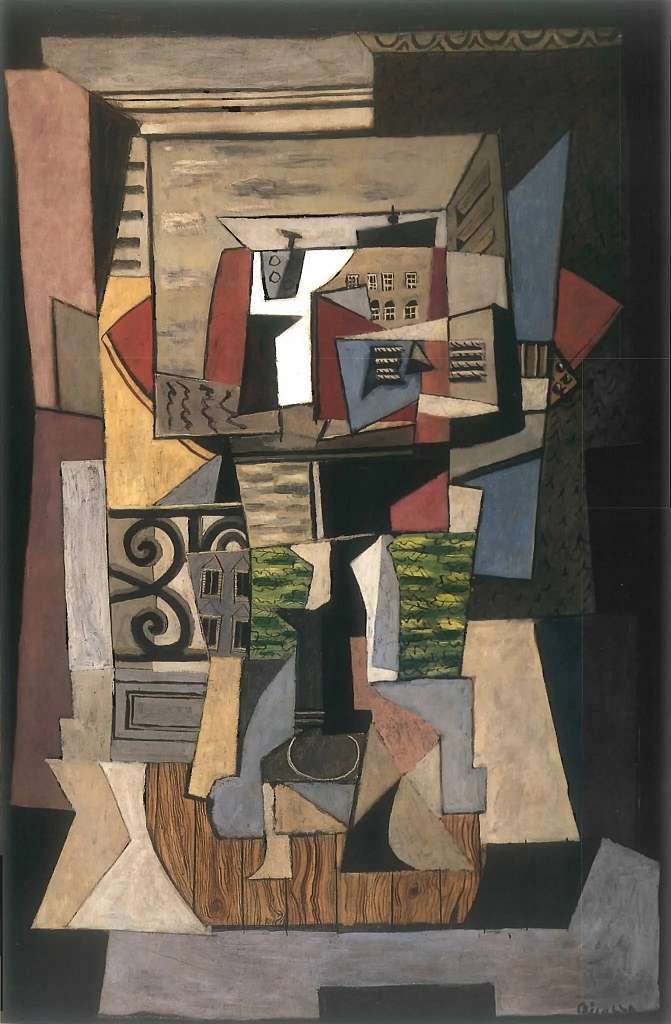

Diba, himself a cousin of the empress, would collaborate with another esteemed architect of his day, Nader Ardalan. “The museum is not just a space for art; it is a place where tradition meets modernity, where the past and the future coexist,” Diba would comment on his creation. Inspired by Neo-Brutalism as well as ancient Iranian traditional architectural forms- the mammoth building set amidst a park scattered with sculptures by international artists such as Belgian surrealist René Magritte and English artist Henry Moore- has halls mostly underground and has come to be monikered “the underground Guggenheim”. The museum would come to house the largest and most important collection of modern art outside of Europe and the USA.

The project to create the museum and the subsequent vast spending spree for the museum’s collections was given an almost open-ended budget approved by both the Shah and his prime minister, and was bankrolled by a great influx of petrodollars from the National Iranian Oil Company. Once the building was complete, Pahlavi would gather some of the most prominent pieces of contemporary Iranian art to be on display in the museum’s halls- from the formerly mentioned Bahman Mohasses to Farideh Lashai. The TMoCA was inaugurated to fete the empress’s 39th birthday in 1977.

Mohasses, Darroudi and their contemporaries’ yearning for a permanent home for their works now sated, Pahlavi decided to take the project to a grander scale. Enlisting the help of some of the international art world’s biggest names, including Donna Stein, a former curator at New York’s MoMA, the empress embarked on an unprecedented effort to secure a collection for the Museum of some of the world’s most coveted pieces of modern art. Of the vast scope given to the collection effort, both financially and in terms of taste, Stein commented to the New York Times that her function was, “to create a statement of history and context and quality and rarity, those were the criteria, not how much something cost. In that respect, it was a dream job.”

The collection would come to feature works by Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Max Ernst, Marc Chagall, Mark Rothko, and Andy Warhol, amongst many other important names. The latter would also go on to make his now iconic series of silkscreen portraits of both the empress (one of which would be destroyed during the Islamic Revolution), the Shah, and the Shah’s twin sister, Princess Ashraf- an ode to the cultural blur between the political and the artistic during that era. Warhol travelled to Tehran during that period to take polaroid photographs of the royal couple which he would subsequently use in creating his prints. Bob Colacello, editor of Warhol’s Interview Magazine, and who accompanied Warhol on his 1976 trip to Tehran would comment in an interview given to The Atlantic, “It [Tehran] reminded me of Beverly Hills, except that they had Persian carpets by their pools.”

Estimated in 2018 to be worth around USD 3 billion, much of the collection has ceased to be on display to the public since the Islamic Revolution due to some of the works depicting scenes deemed to be in discord with the state’s religious mores. Some of the works have been shown to the public in exhibitions held in 2005 and in 2024 when many unveiled women were seen taking selfies amidst pieces by Warhol and de Toulouse-Lautrec- a nudge to the softening nature of the state’s tolerance towards things that had been deemed non-negotiable since 1979.

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art remains today what it was intended to be, and politics aside, it has continued to be a home to works by the country’s leading contemporary artists, and is accessible to art lovers, with a ticket costing around the equivalent of 14 cents USD. All the old works collected by the empress and her team have remained the property of the Museum, political upheavals, social changes, and economic realities notwithstanding. “In 2005, the director of the museum at the time did put on an exhibition of the paintings—not all of them, of course. I am happy that the people saw what they have. I will never forget an Iranian painter lady who told me that when she found herself in front of a Rothko, she had tears in her eyes. That was important to me. Everything is still there,” commented Pahlavi in an interview with W Magazine.

Iran and its culture is stereotypically viewed through the Western lens by its politics- from the Shah’s excesses to the conservatism of the Ayatollahs- and what is forgotten in the general international discourse on Iranian culture is the group of remarkable artists, patrons of the arts, and lovers of the arts who for centuries had championed Persia to be a place of beauty and of dedication to fine aestheticism. Perhaps it is time for us to again view this ancient culture in that way and reposition it to its rightful historical place as a vibrant place of creation and connoisseurship.

In the same 1970 interview, Mohasses, when asked about the role of the artist vis-à-vis the Iranian public, he commented, “The artist connects with people through his work, and when society recognizes the necessity of the artist’s work, this connection will be authentic and deep. Otherwise, it will be superficial and artificial. First, we must see whether painting is necessary here or not. From what I can feel from our experience, we sense that society has not yet felt this necessity.” Judging by the immense public interest and attendance in the Museum’s ongoing “Eye to Eye” exhibition which features over 120 pieces of international as well as Iranian modern art, it seems the Iranian society has now “felt this necessity”, with the legacies of these masters of Iranian modern art continuing to live and breathe through the mouth of the Museum.