Posted in

Art & Photography, art

Posted in

Art & Photography, art

What are we willing to see with Mohamed Bourouissa?

Text Sarah Daoui

I first encountered Mohamed Bourouissa’s work at 18, searching for a visual vocabulary to make sense of my own identity. Growing up in a predominantly white town in Upstate New York, I craved images that could speak to what it means to be Algerian today. Yet, almost all of the imagery I could source online dated back to Algeria’s 132-year colonial past. Stills from The Battle of Algiers (1961) and Marc Garanger’s Femmes Algériennes (1960) that I found initially captivating eventually left me unsatisfied. I sensed that my generation of the diaspora was no longer solely defined by colonial framing; that while our history might be a common point of departure, there must be a shared sentiment shaping our present, something that, even if intangible, was immediate in a contemporary context. But from my vantage point, as a university student in New York, where Algeria was mistaken for Nigeria on an almost weekly basis, that feeling remained out of reach and unconfirmed.

Art helps us find answers, and Mohamed Bourouissa was the artist who spoke to my existential teenage questioning. The first body of work I encountered was Horse Day (2013–2017), in which he photographed Black cowboys in Philadelphia. A single image from the series, documenting riders from the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club, managed to dismantle Hollywood’s monopoly on my popular imagination of a cowboy.

From there, I turned to Nous Sommes Les Halles (2003), a series of photographs resulting from Mohamed’s time spent around one of Paris’s most central transit stations, Châtelet–Les Halles, where he documented teenagers coming into the city from the banlieues. It was the first time I had seen images of youth from the outskirts of Paris represented on their own terms. Their freedom, style, spirit, and even Mohamed’s presence came alive through his time capsule–like intimacy.

Mohamed’s breakthrough series, Périphérique (2005–2008), features a set of staged scenes of his friends and acquaintances in the banlieues during the 2005 Paris riots. The images read like a Delacroix painting, with carefully posed scenes and frozen gestures exuding a dramatic stillness. Instead of a Delacroixian Orientalist fantasy, the images carry a palpable tension of real people— in confrontation and love, in resistance and endurance— during a very specific moment in French history.

A work I return to often is Sans titre (2017). On a sheet of sketch paper, an image from Horse Day of a Black cowboy in Philadelphia is superimposed onto an image from Périphérique. These two images are shot nearly a decade apart and set in worlds that rarely intersect, yet they seamlessly fit together in a single frame, mirroring one another with haunting clarity. It’s ultimately not about being Black or American, or both; Algerian or French, or both. It’s about existing beyond society’s popular imagination. These quietly radical images that we don’t often see gave shape to the abstract feeling I once lacked language for but immediately embraced.

This tension, between intimate narrative and structural violence, isn’t incidental in Bourouissa’s practice. Mohamed was born in Blida, Algeria (1978), the same city where Frantz Fanon conducted his revolutionary psychoanalytic studies to decolonise the psychiatric institution during the Algerian War of Independence. It was in Blida that Fanon began helping patients confront the psychic effects of colonialism, work that would lay the foundation for Black Skin, White Masks (1962) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961). Today, a psychiatric hospital in the city honours his name, and it’s there that Bourouissa’s aunt works, tending the hospital garden. This personal relationship to Frantz Fanon’s garden inspired his botanical installation, Brutal Family Roots (2020), as seen in his solo exhibition at Palais de Tokyo, where he traced the genealogy of how certain plant species, such as the mimosas plant, originated from Australia, are now found across the Mediterranean, including in the Frantz Fanon Psychiatric Hospital’s garden. Through both a personal and universal interrogation, the mimosas become a metaphor: naturalised, displaced, resilient.

Mohamed’s work is about uncovering the tension between what’s documentary and fiction, personal and universal, imagined and real. It rejects the bounds of any single geographic denomination, period, political affiliation, or form. Rather, it subversively asks us to look more slowly, dig deeper, and interrogate the systems that shape our lives and collective imaginations. Across his two-decade-long career, Mohamed has rejected conforming to form. His projects have spanned photography, sound, sculpture, and even botanical installation. This resistance to readability and predictability is not to obscure meaning, but to expand it. Each medium becomes a new access point into the same urgent questions on how we see, categorise, and relate.

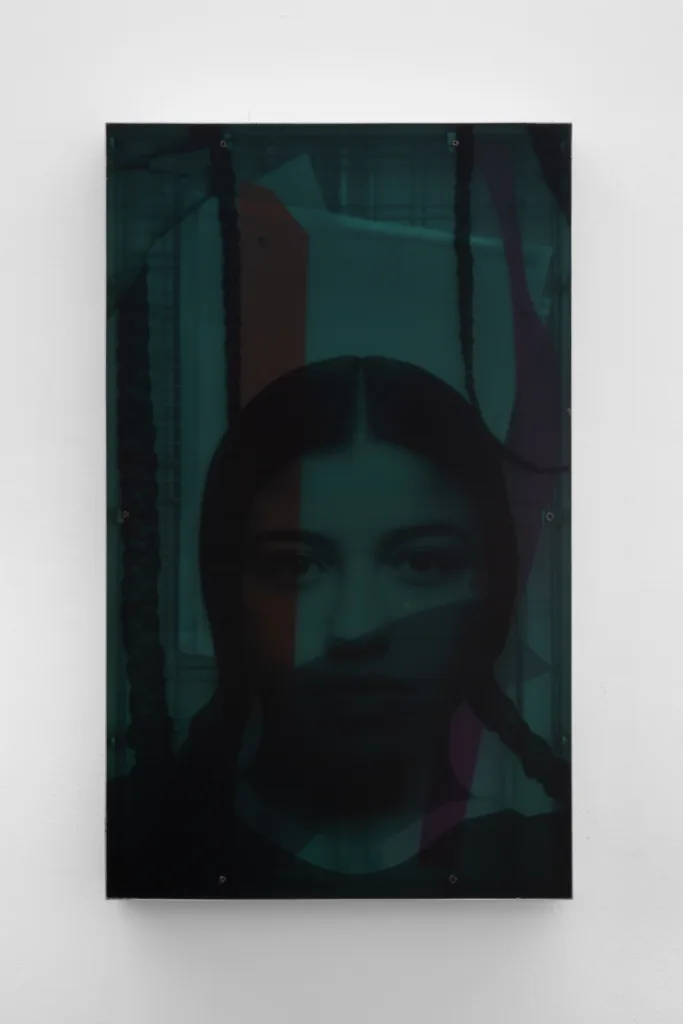

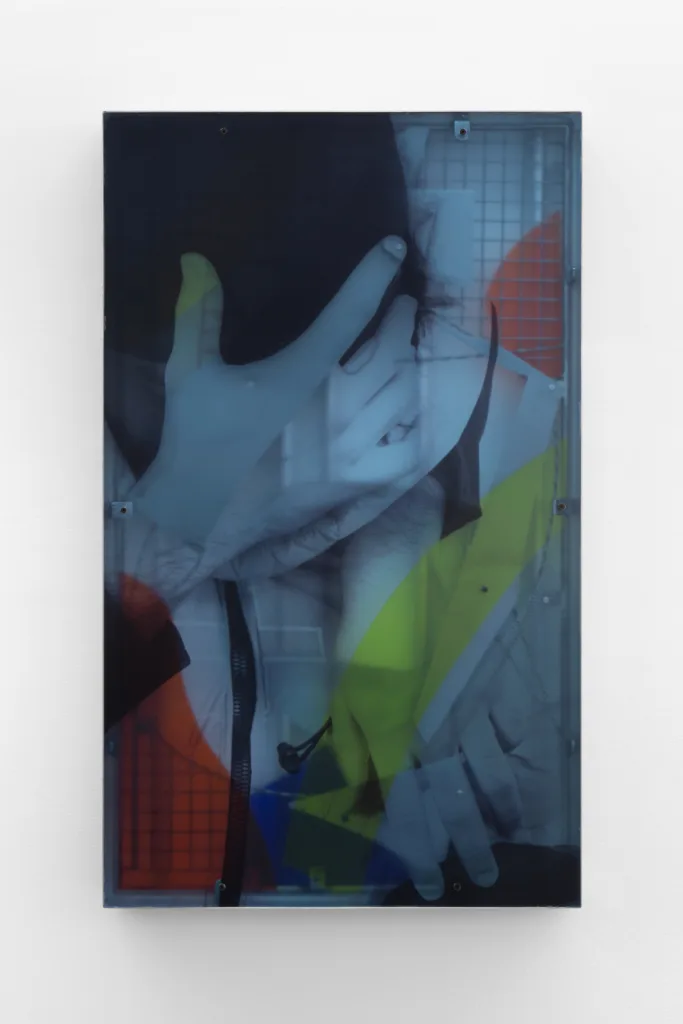

His most recent solo exhibition La Généalogie de la Violence (2025), on view at Kamel Mennour, Paris, extends his decades-long investigation into the invisible architectures that shape our social and psychic realities. The exhibition features a short film by the same name of the exhibition, and a sculptural-photographic series titled HANDS, created as a tangible extension of the film. The film unfolds in the most mundane of spaces: a car. Two young adults sit together in a third space very familiar to kids of suburbia, innocently talking, subtly flirting. Then, flashing police lights. What follows is a series of dissociative and disorienting CGI sequences that use a sci-fi visual language to take the viewer on an experiential trip through the psychological residue of racial profiling and systemic control. While no violence is shown, its presence hangs heavy. It’s a narrative without a climax, but not without consequence.

As Frantz Fanon’s work teaches us, systemic violence is spatial, linguistic, and psychological. In HANDS (2025), Mohamed gives that violence a material form. The works aren’t traditional photographs; they’re repurposed archival images, printed on plexiglass, fragmented, and superimposed on metal grids and industrial plates. They appear to look like lightboxes, but there’s no light behind. At first glance, they feel cold, bureaucratic, and surveillant. The closer you inspect, the more the images reveal themselves: the body as object, dislocated, cropped, framed, reframed – all within the landscape of the grid. Images of hands are featured throughout the works: some reach, some resist, some simply exist. For Mohamed, the grid is more than just a compositional structure. It echoes physical and psychic architectures of control: fences, prison bars, bureaucratic frameworks, and the conceptual systems that categorise and contain human beings. There’s a striking parallel to be made between these metal structures and the invisible systems that mark people for surveillance: race, class, geography.

Evoking everything from prison architecture to data matrices, I found the usage of the grid in HANDS to be in quiet conversation with one of Bourouissa’s earlier works, Temps mort (2008): a short film shot by Mohamed’s two friends on a contraband flip phone in prison. The film is the result of a year of videos, images, and text messages shared with Mohamed.

Through lo-fi imagery, we experience his friend’s grid-like vision of the world through a prison window. “I wanted to explore what it means to be locked up, to be denied freedom. It’s a question of control and body, that could have been set in any country, in any society. This control of expression– it’s intimate, personal, and universal.” In both HANDS and Temps mort, the grid becomes both a literal and metaphysical trauma: it freezes, immobilizes, and reduces. And in this immobilisation, Bourouissa’s images fight back — not with spectacle, but with quiet refusal.

In his current exhibition, Bourouissa cites Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, and especially the line that inspired the series: “La grille est un moment terrible pour la sensibilité, la matière” (“The grid is a terrible moment for sensitivity and matter”). The violence Mohamed depicts is not explosive, but structural. It proposes an alternative function for the image: to resist. It’s within the stillness between HANDS and Généalogie de la Violence that this resistance begins. One moves, the other is still. One tells a story, the other fractures it. Together, they enact Bourouissa’s broader project — to reveal the invisible frameworks of domination, and to make space for those pushed to the edges of the frame. In Paris’ Saint Germain, his exhibition asks: What happens when we look beyond the spectacle? What are we willing to see?

In the days leading up to the opening of La Généalogie de la Violence, I had the privilege of spending time with Mohamed in his studio. As he walked me through his upcoming projects, what struck me most was not just the clarity of his own vision, but the generosity with which he championed the work of others. When I asked what he’s been looking at lately, his eyes lit up as he spoke about Palestinian artists like Taysir Batniji, and his commitment to organizing exhibitions to uplift their work. This summer alone, he’s helped mount a series of events across the Institut du Monde Arabe, Gennevilliers, and the Bourse de Commerce — quiet acts of solidarity that echo the ethos at the heart of his own practice.

Witnessing this side of him reminded me of why I was drawn to his work in the first place. At 18, I was searching for images to help ground my sense of self. What I found in his practice was not identity in fixed terms, but the recognition of a feeling, experience, and complexity. Defined by a refusal to remain still and a commitment to building new ways of seeing, the work is for those of us who grew up looking for ourselves in pictures and rarely found them. The images don’t scream. They ask. They press. They persist. And they wait for us to do the same.