Posted in

Feature, book

Posted in

Feature, book

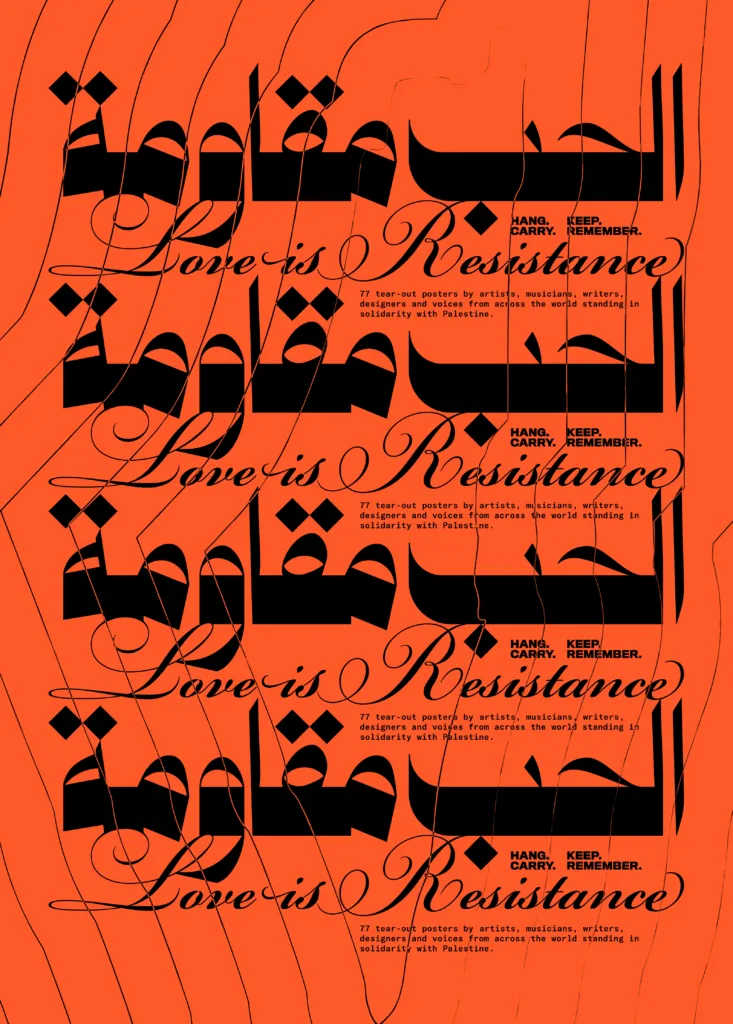

Love is Resistance: The new poster-book redefining the line between art and activism

Text Selma Nouri | Cover designed by Hey Porter!

In Recognizing the Stranger, Isabella Hammad writes, “If there is another lesson I learned here, in the episode of writing my depressed story, it was the quite basic one that literature is not life, and that the material we draw from the world needs to undergo some metamorphosis in order to function, or to even live, on the page.” The same, I believe, must be said of art.

While art may sow the seeds of revolution, its enduring power lies in our collective capacity to mobilise it – “to undergo a metamorphosis,” as Hammad suggests. For art to “live on the page,” it must transcend fleeting moments of epiphany and transform into sustained and meaningful action. In archiving and exhibiting art, we endow it with this potential to evoke our shared humanity,cultivating solidarities across lines of difference and catalysing real political change.

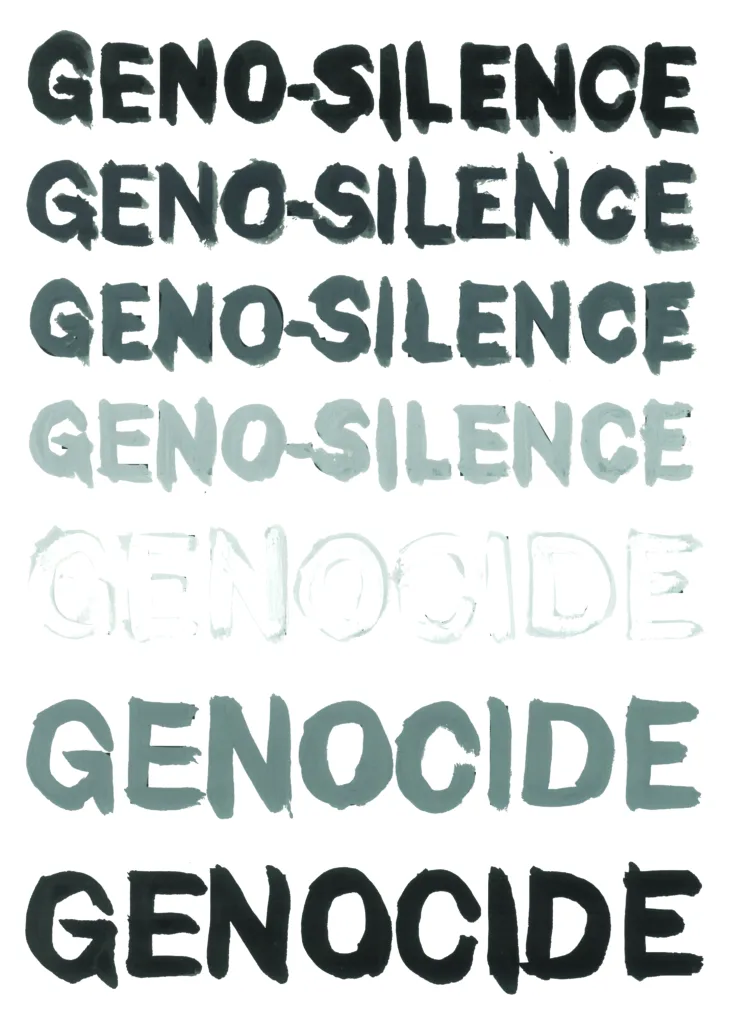

When understood in this way, cultural institutions, galleries, art books, and Instagram accounts become more than repositories of aesthetic value; they operate as living archives of radical thought–sites of reflection, resistance, and collective memory amid political upheaval. Drawing on her work as a cultural strategist and curator, Aya Mousawi, the author and founding editor of Love is Resistance, quickly recognised the critical importance of archival practice amid the ongoing genocide. “Urgency,” she says, “is born from the ache of witnessing…to archive this time and capture the spirit of our efforts to stand with Palestine is to honour their resistance and survival, to trace the threads of solidarity that connect all of us.”

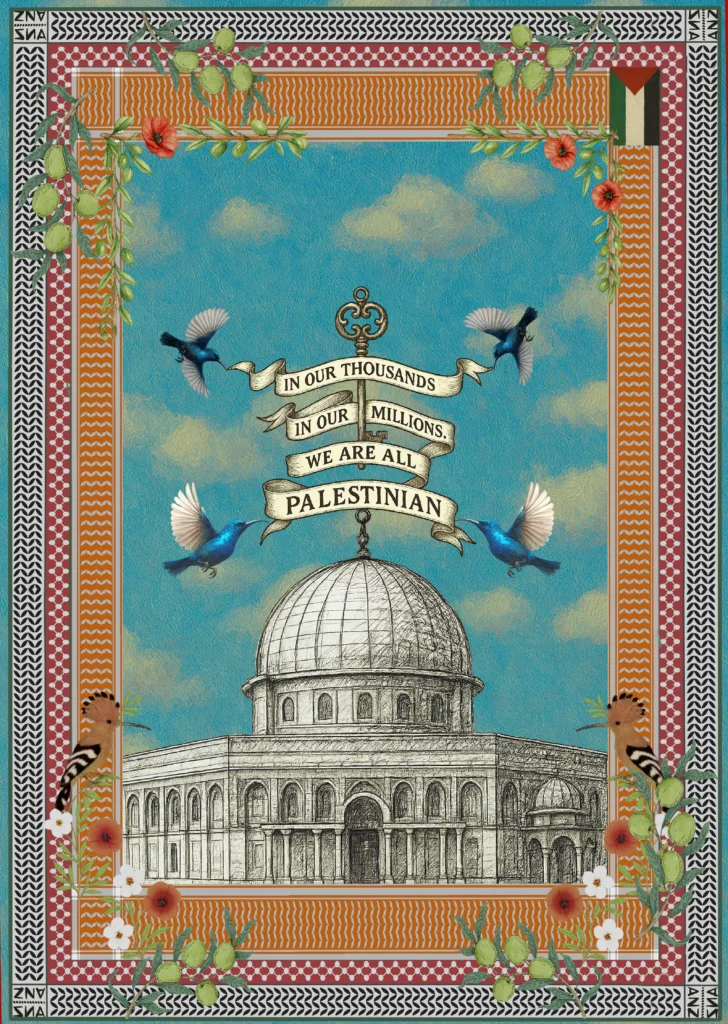

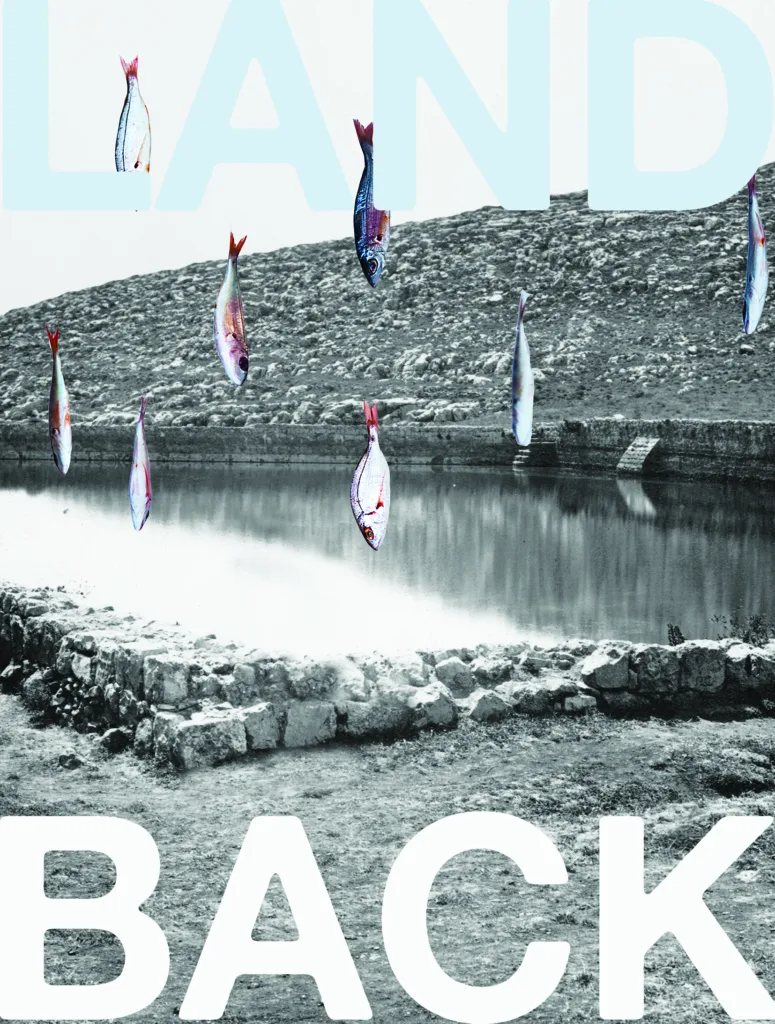

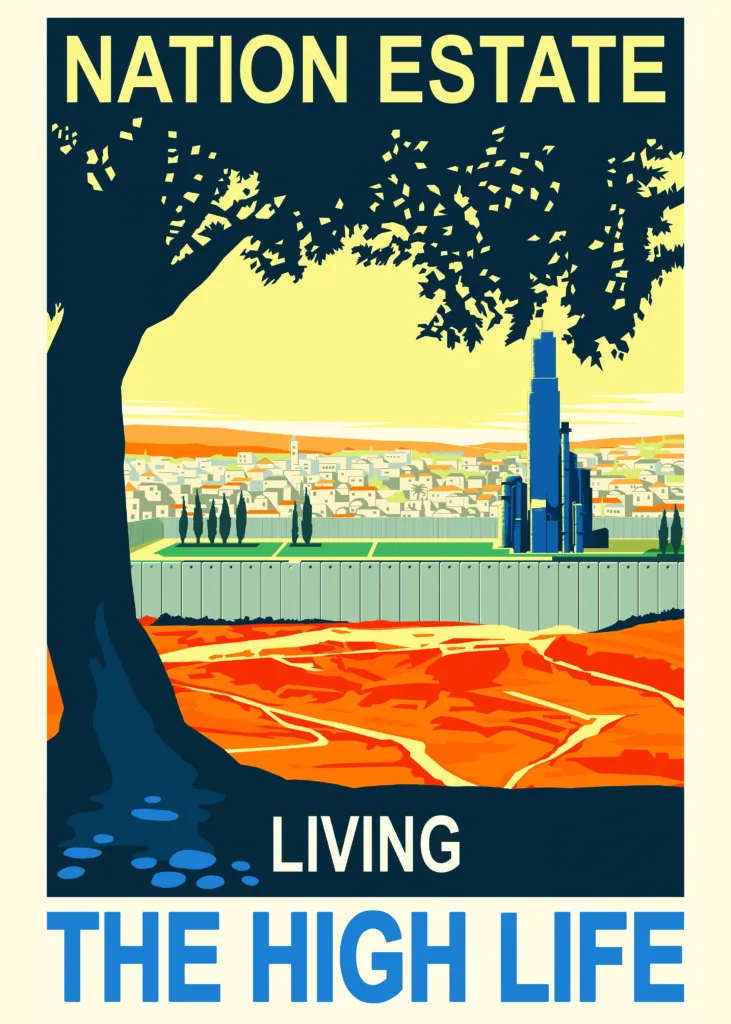

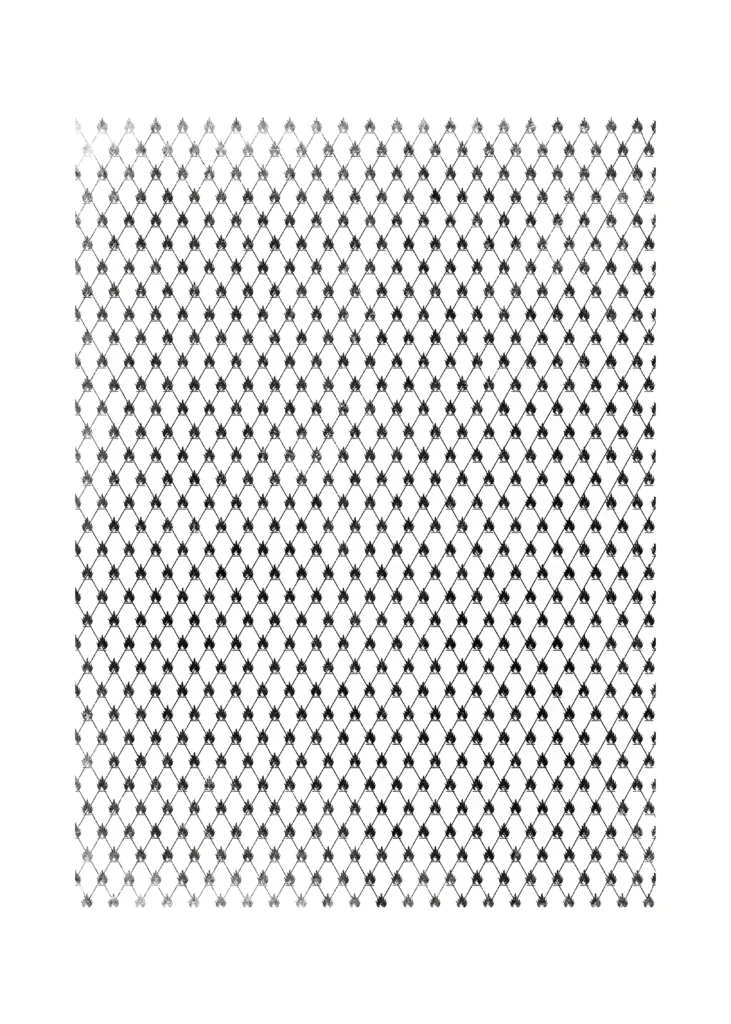

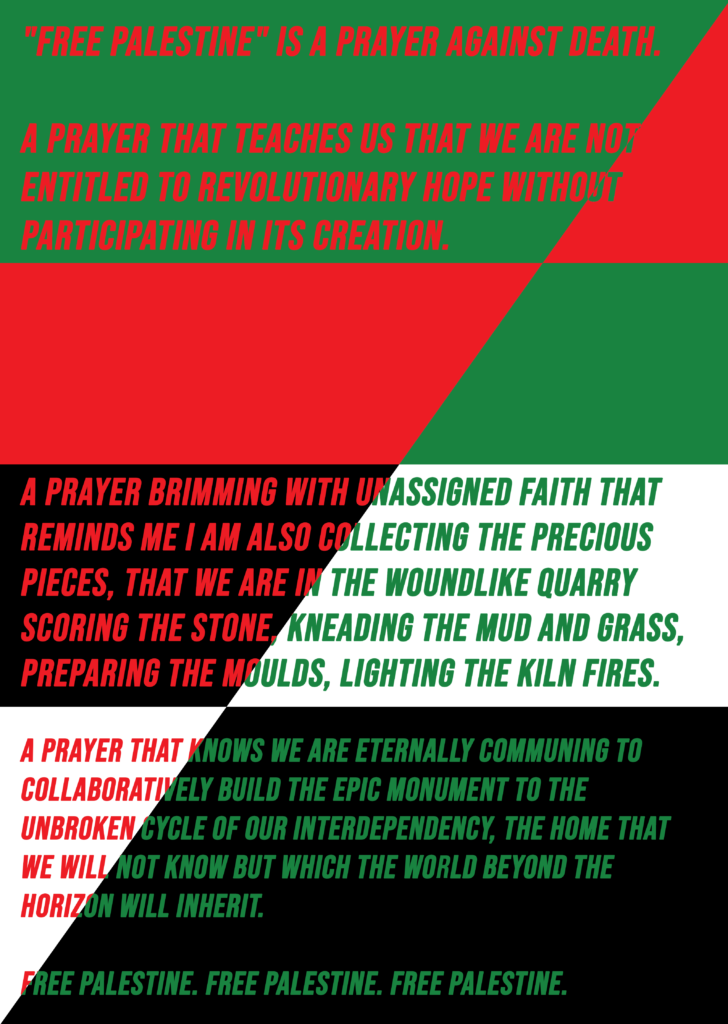

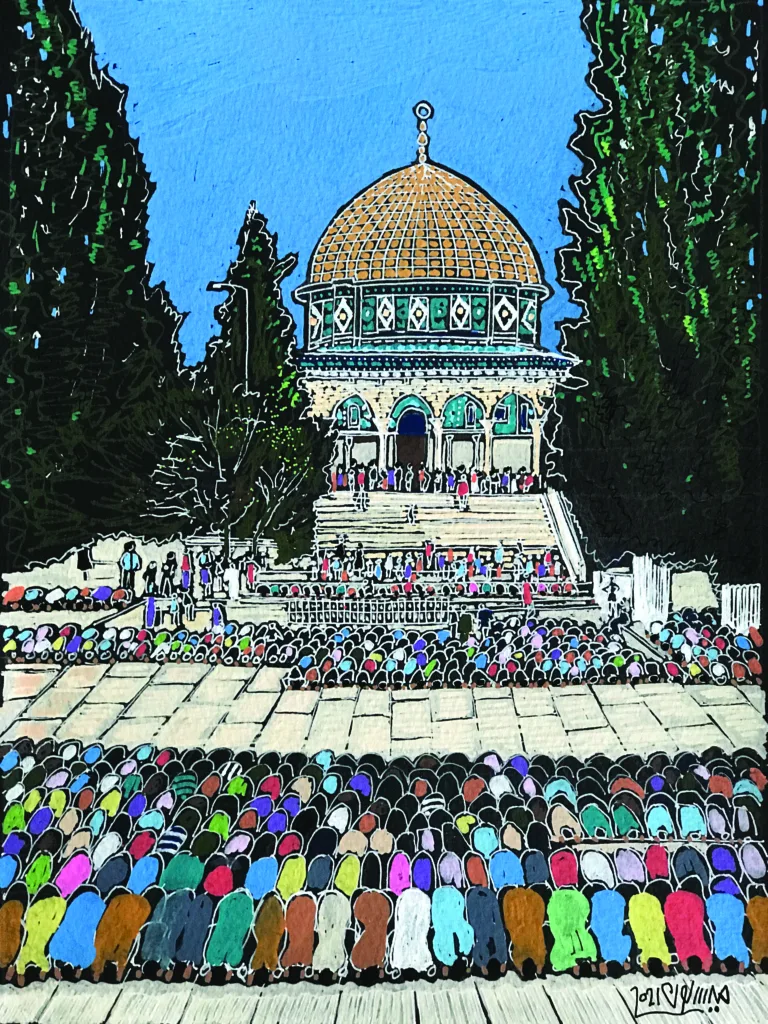

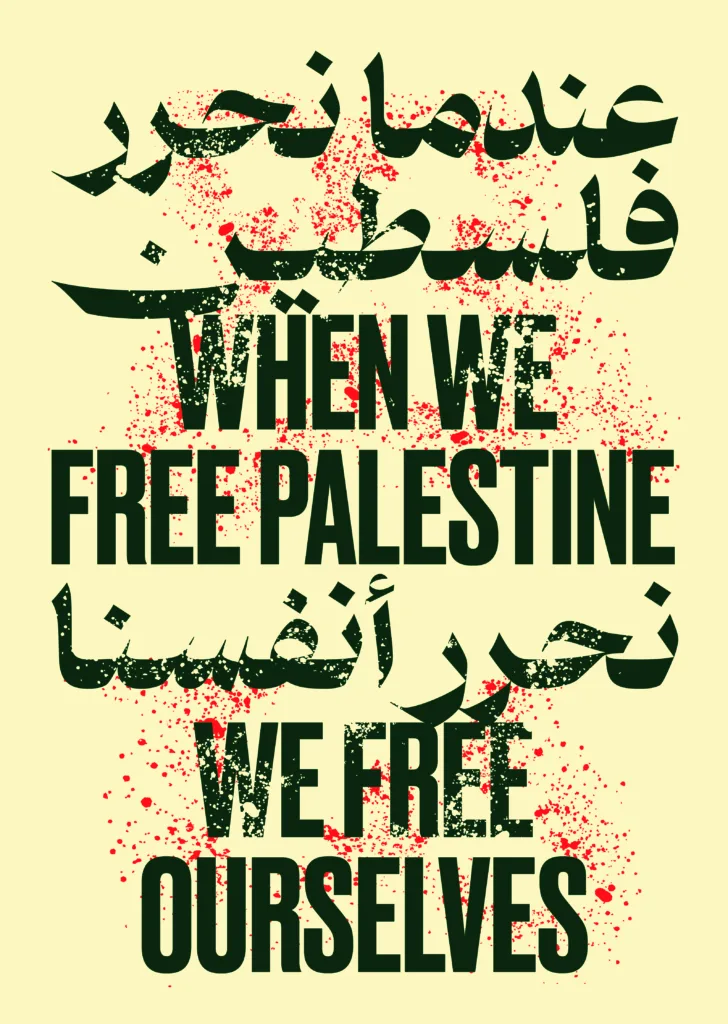

Published by Saqi Books and currently available for pre-order, Love is Resistance features 77 commissioned tear-out posters by artists, writers, students, and activists from around the world, including Ahmed Shihab-Eldin, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Ibrahem Hasan, Samia Halaby, and many more. “I came up with the idea in early June while waiting for a friend at the Barbican,” says Mouswai. “I was browsing through the bookshop when I came across a Black Lives Matter publication featuring thirty commissioned posters by Black artists. I just thought, ‘Wow…at a time when millions are shutting down cities and flooding the streets, this is exactly the kind of visual intervention we need for Palestine.’ I immediately put out a call for contributions among friends and colleagues, and ultimately commissioned exactly 77 posters to mark each year of occupation.”

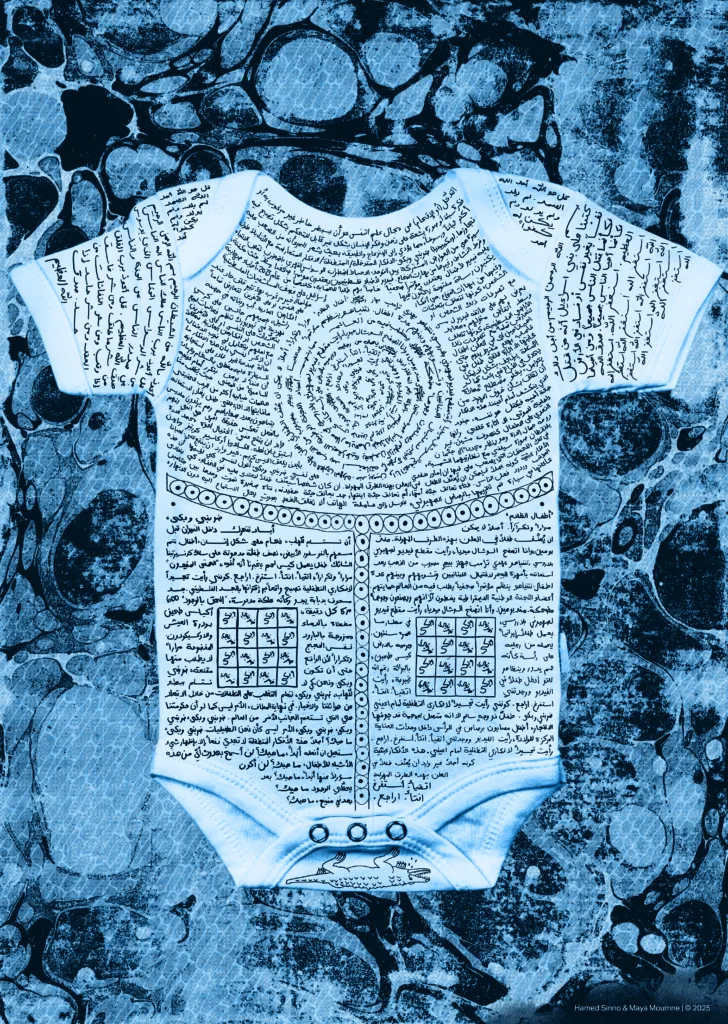

Just three months after that initial spark of inspiration, the 38 x 27 cm poster book is set to launch at the end of October. All proceeds will go to the Ayjal Foundation, an organisation dedicated to providing long-term rehabilitation and psychosocial care for children, along with essential on-the-ground support for displaced communities in Gaza. “Of course, their efforts to address the immediate needs of families in Gaza are critically important,” explains Mousawi. “But what I find most powerful is their long-term vision. They are investing in Palestine’s future by directly supporting children whose lives have been devastated by occupation and genocide. There is no existing therapy model for what they’ve endured. We can’t even begin to imagine what full rehabilitation would require. But Ayjal is doing that work. They’re creating manuals to train teachers, building tools to support generational healing, and I think it is absolutely vital that we support this work.”

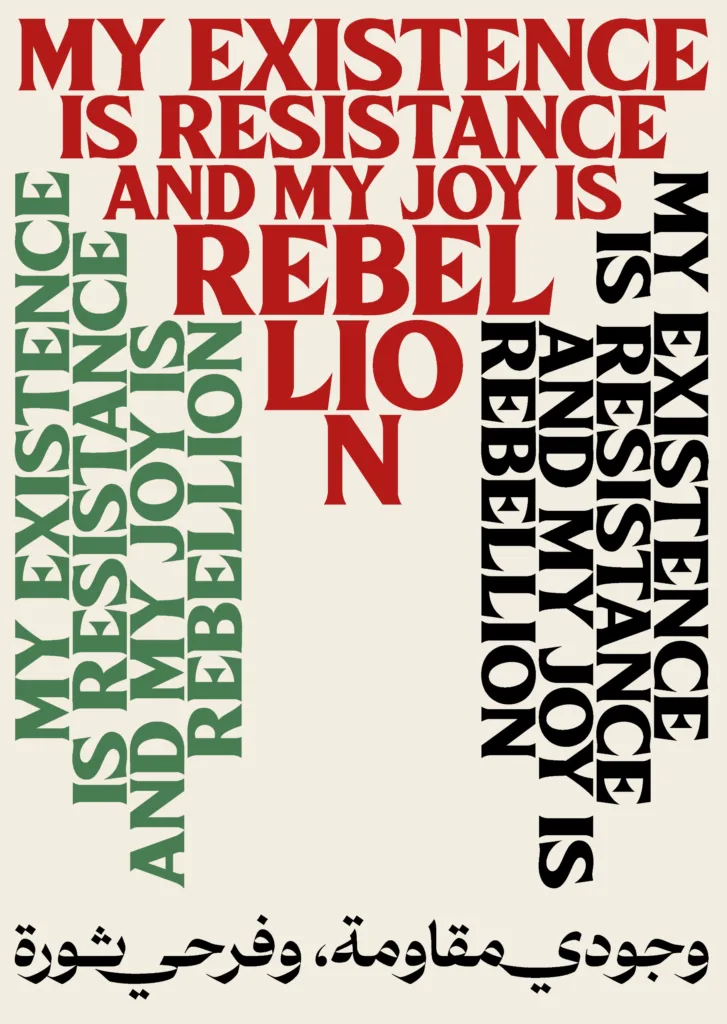

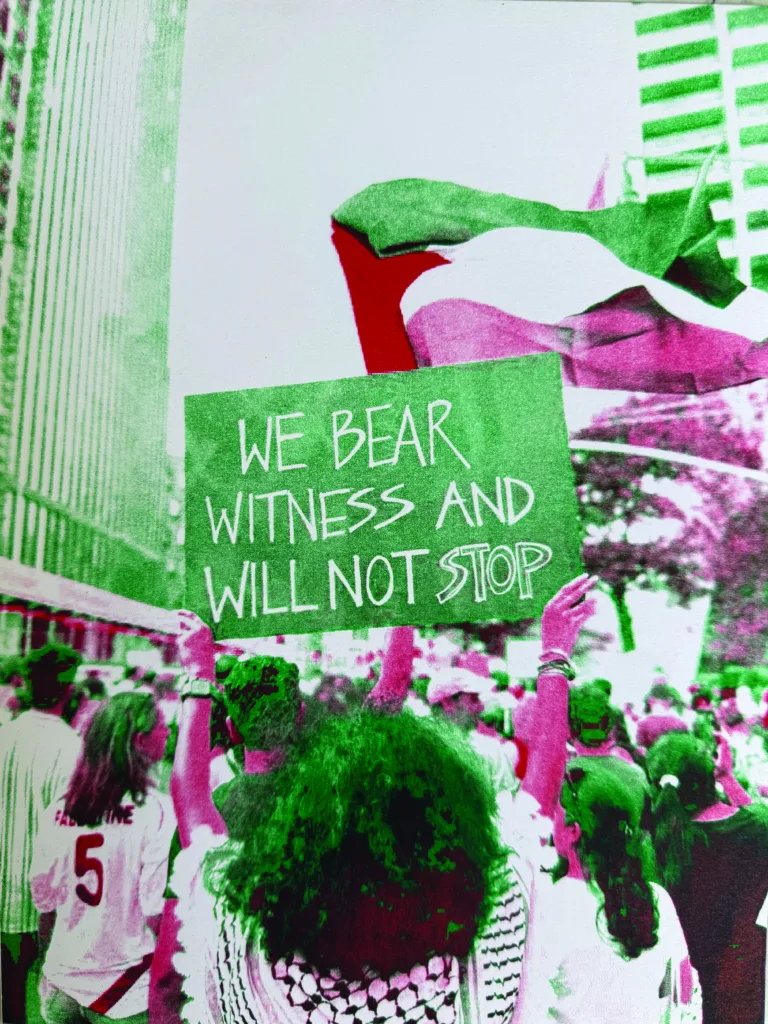

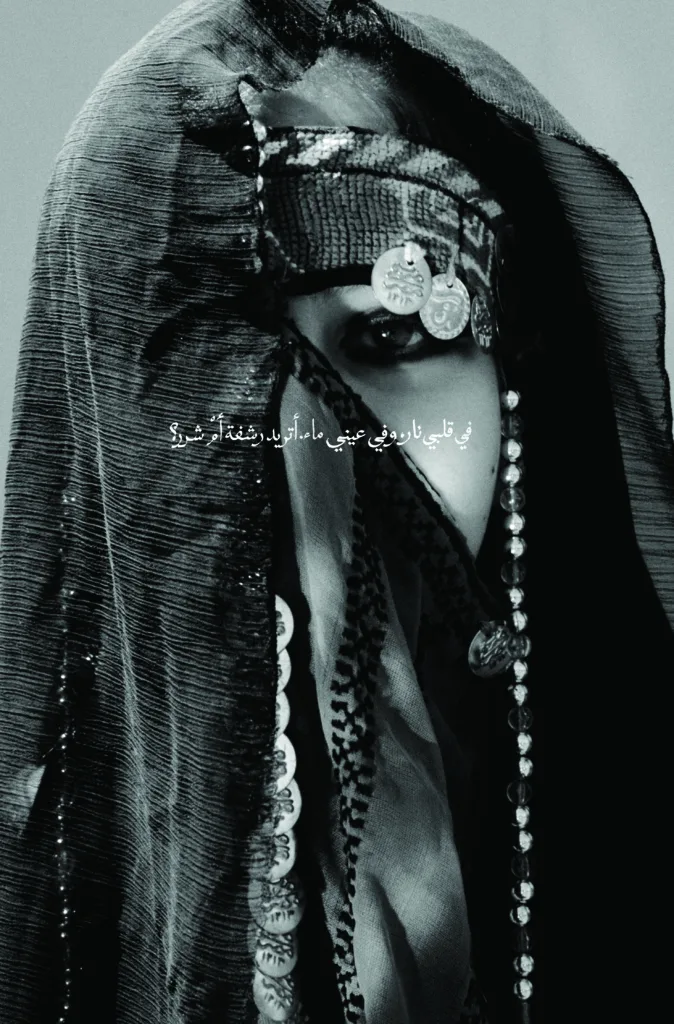

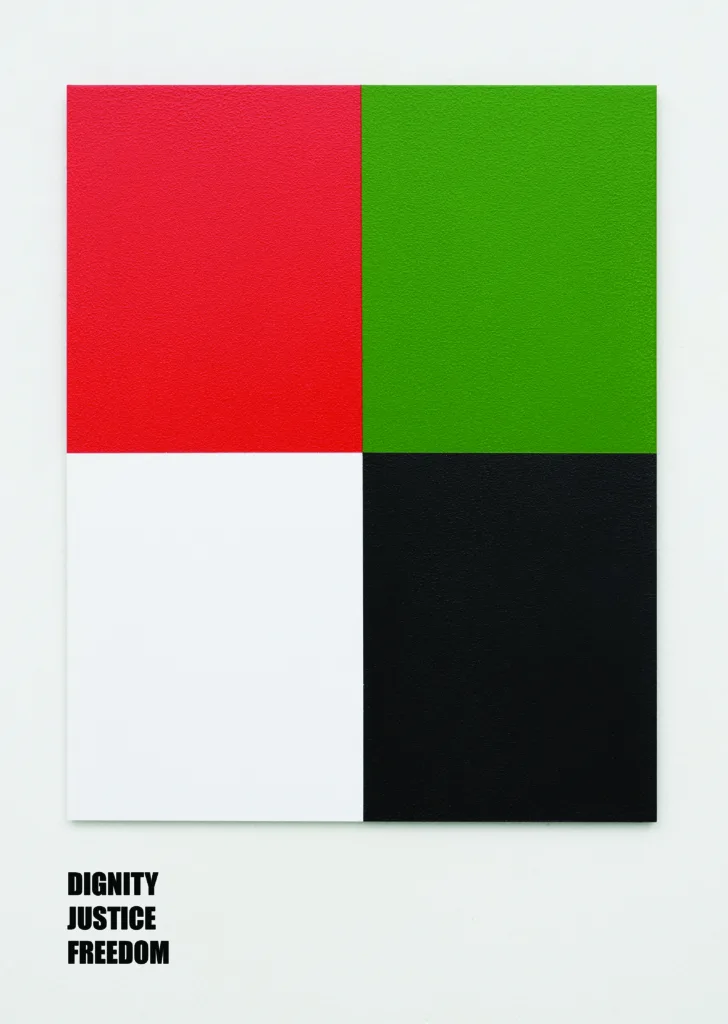

For Mousawi, each poster in the book represents a fragment of a larger collective narrative. “They almost feel like screenshots,” she says, “capturing stories and safeguarding memories that reflect both the historical legacy and the ongoing realities of the Palestinian struggle.” From Wear the Peace’s tribute to Khaled Nabhan’s Soul of My Soul, to Samia Halaby’s 1969 liberation graphic – which reimagines the Palestinian flag as a symbol of global revolt – these works converge to form a powerful visual archive, one that not only expresses solidarity, but reclaims love as an active form of resistance, a shield against historical amnesia. “It is a defiance against the machinery of oblivion,” For the foreword, writes journalist Ahmed Shihab-Eldin, a refusal to give in, to forget, or to be forgotten.

As Author, theorist and curator Shumon Basar notes in the book’s epilogue, there is enduring significance in preserving what has been shared, created, and witnessed during moments of collective trauma – and this is especially urgent in the context of Palestine. The circulated posts and handwritten placards, the photographs and videos documented by Bisan Owda, the poetry of Refaat Alareer, the voice of Hind Rajab, and the posters compiled in Love is Resistance – these are all “records of a world permanently altered,” he writes. “To love, here, is to refuse erasure. To resist is to remember. And to remember is to make sure the world cannot pretend it didn’t see.”

But the pivotal term here is pretend. The archiving of art and crucially today, the archiving of posts, plays a central role in the politics of memory. Yet memory, without transformation, risks becoming spectacle. After decades of Israeli occupation and two years of genocide, we are forced to ask urgent questions: What happens when cultural or archival spaces are co-opted by the very imperial structures they claim to oppose? What happens when our engagement with art becomes passive?

Archiving, I believe, risks becoming an empty gesture when moral consciousness remains dormant, when empathy is selective, performative, or feigned. While society may celebrate revolutionary art, the genocide has exposed how deeply we’ve internalised a culture of passive consumption, one where even the most powerful images are emptied of consequence in the face of our complicity.

For Mousawi, it is precisely this prevailing condition of apathy and affective resignation that Love is Resistance seeks to challenge. Its central commitment, whether directed toward Palestine or broader systems of injustice, is to resist the politics of indifference by asserting love as a mode of revolutionary praxis. The posters, conceived as intentional acts of resistance, do more than reflect social realities; they affirm art’s capacity to actively intervene and reshape political life. In this way, Mousawi articulates a new mode of archiving, one rooted in the sustained refusal of erasure through deliberate, collective action.

As Basar observes, if the past two years have taught us anything, it is that “everything matters” in the ongoing struggle for justice. Were this not the case, he argues, “Israel would not expend such extreme forms of energy to suppress us,” he says. “When you think about it, the strange thing about ‘strength’ (political, economic) is how fragile it also is. Israel, and Zionism, insist on being the biggest victims, while dropping the biggest bombs on flimsy tents in malnourished camps that have already been bombed several times. The ‘Media Industrial Complex’ works in concert with the other ‘Industrial Complexes’: Military, Financial, Entertainment. Democracy (if it ever really existed), is directly proportional to the education of its citizens. It’s why the first thing fascist governments do is rewrite history curricula at school. Culture, in all its forms, now has the burden of responsibility to defend against this perversion of the past and present.”

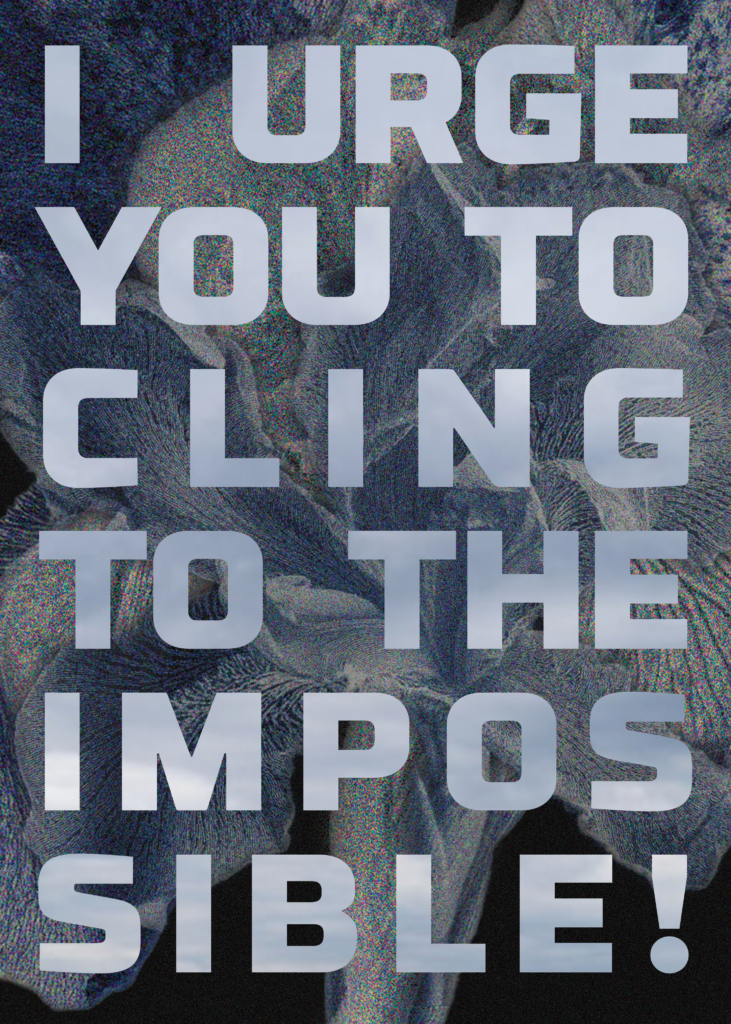

Indeed, in reflecting on the significance of a work like Love is Resistance, Basar emphasises its role in cultivating resilience precisely through this deliberate and sustained cultural intervention. In an era where “deepfakes are rewriting what is truth,” these posters serve as a vital counterforce, incontrovertible evidence of what cannot be rewritten. Ultimately, Basar contends, this vital work relies on the dedication of artists, writers, and editors like Mousawi, whose resolve to act in the face of pervasive resignation is indispensable.

“Ever since the genocide in Palestine began,” he explains, “I have felt closest to those who share my experience: oscillating between rage and despair, minute by excruciating minute. Aya [Mousawi] is one of those exemplary individuals who feel morally compelled to resist paralysis in the face of overwhelming suffering. Thus, the title – Love is Resistance – also serves as a profound articulation of Aya’s proactive outlook, which has inspired everyone involved in this project.” In continuing to reflect on Basar’s words, I am convinced that this outlook will also influence those who engage with the book – those who transform the posters from symbolic artworks into embodied acts of resistance.

“Each poster is designed to be used,” explains Mousawi – whether pulled out, framed and hung, taken to peaceful protests, or preserved collectively as part of a broader arsenal of dissent. “I like the idea of posters because there is something light about them,” she adds. While the project is deeply rooted in visual expression, the deliberate choice of the term poster serves to distance the work from the aesthetic and institutional expectations associated with fine art.

Instead, it positions visual culture as accessible, functional, and action-oriented. The poster, in this context, becomes a democratic medium, one that invites active engagement, circulation, and use rather than passive spectatorship or distant reverence. “I want people to use the posters,” Mousawi emphasises, “to not be so precious with them.”

As Basar continues in the book’s epilogue, the etymological root of the term poster is post, a term that functions dynamically as a verb and unapologetically as a noun. To post – whether on a wall, a lamppost, or a digital platform – is to reject inertia and to assert a visible presence in public space. For a poster to be successful, he says, it must work from afar: “It has to be devastatingly simple but carry complex meaning. It has to make you smile while making you want to change everything that prevents the world from achieving its hidden historic potential; decent for every decent being, animal, mineral, or human.”

Remarkably, this is not a power exclusive to Turner Prize winners alone. Poster-making only requires a basic understanding of human decency. Revolutionary art, and by extension, revolutionary action, can emerge from anyone. “This is why I felt it was important that the book’s contributors were not just artists,” explains Mousawi, “because everyone has something beautifully complex and meaningful to say, from the kids at the Ayjal Foundation to journalists like Miryam Francois.” This inclusive participation underscores the project’s democratic nature. Every poster is designed to intervene in public discourse through circulation and display. In this act of placement and movement, both the artist and the viewer become active participants in a broader cultural resistance.

“I know some people will probably question the value of this book,” Mousawi reflects. “They might ask, ‘What are these posters going to achieve?’” Yet, she resists the premise of such scepticism. “Everyone has a role to play in this,” she says. “Every voice, in every space and every sector, is necessary.”

For Mousawi, the pursuit of a Free Palestine will not be achieved through singular, monumental acts alone, but through the accumulation of countless small efforts across multiple sites of engagement. “No matter how minor a gesture may seem, it carries meaning,” she asserts. “All of us could easily sit around and cry all day, and I am sure we have all felt that impulse at some point. But when we resign ourselves; when we become paralysed, that is precisely when the oppressor wins. And we cannot allow that.”

Mousawi insists that even the seemingly simple gesture of creating, displaying, and sharing posters – carrying them at protests, hanging them on walls, or sharing them with friends – is not frivolous or incidental. “These gestures constitute a cultural praxis of resistance,” she says, a refusal to forget, a refusal to return to the status quo, and above all, a refusal to be complicit.

As Basar aptly notes, “Posting can be a flotilla if there’s enough critical mass.” The act of posting, then, extends far beyond the digital realm, making its way into our streets, buildings, and the shared spaces of everyday life. To saturate these spaces with the visual language of resistance is, in itself, an act of love, a form of cultural intervention that those in power may neither recognise nor understand until it is too late. This, Mousawi suggests, is the nature of our struggle: art as our form of warfare, and love as our most powerful weapon.

“For us to ever see a free Palestine, we need to love like the Palestinians,” she insists. “Their resistance is fundamentally rooted in a radical ethic of care, a deep and enduring love for their people and their land.” This stands in direct contrast to the violence and hatred of the oppressor. But ultimately, she argues, “We all know that love outweighs hate. This is why love must infuse every gesture toward liberation, no matter how small. That, I believe, is the key to meaningful resistance.”

Book available for purchase at https://www.loveisresistance.art/