Posted in

Art & Photography, art

Posted in

Art & Photography, art

Tasneem Sarkez’s Algorithmic Still Lifes

Text Sarra Alayyan

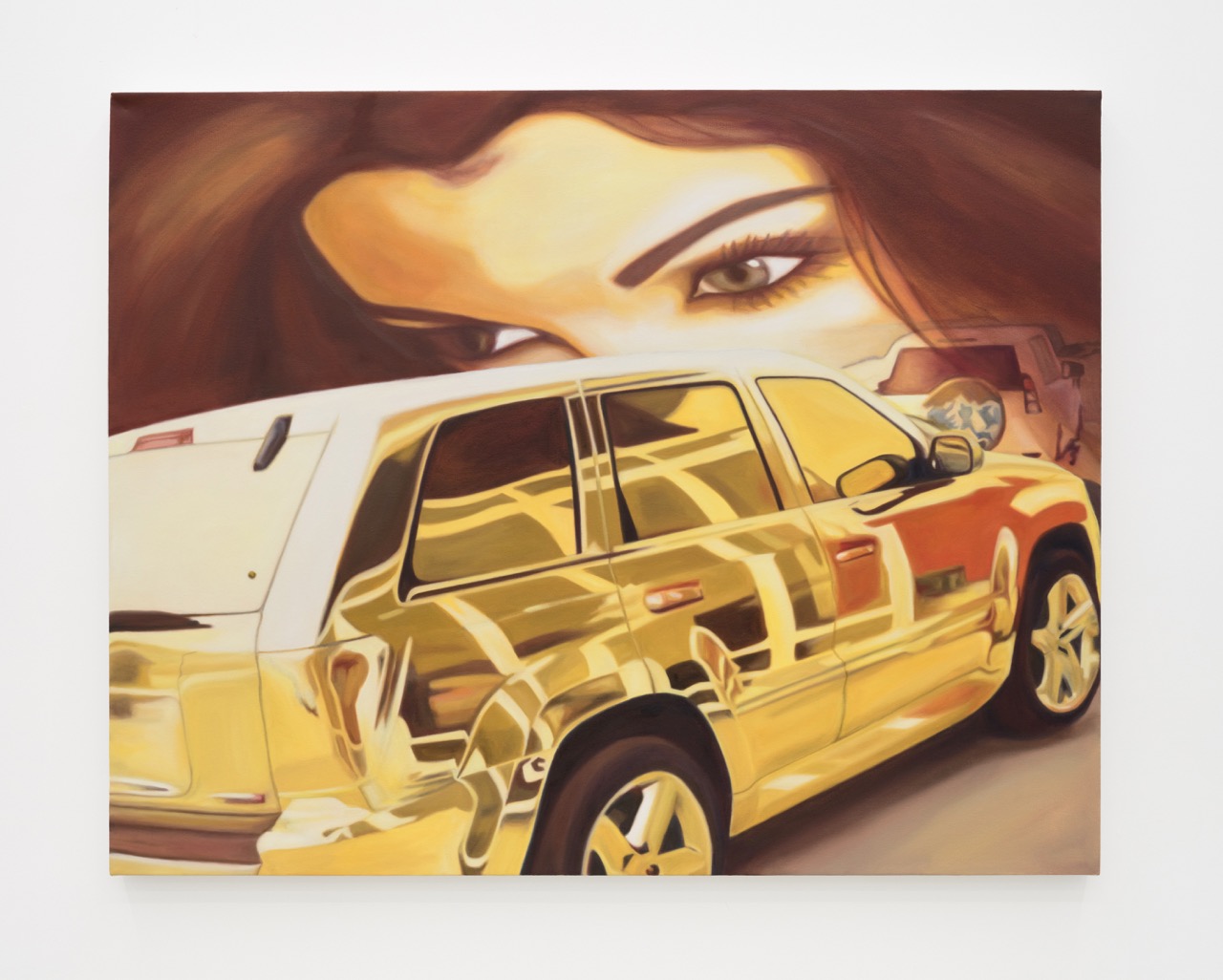

Perfume dupes labelled “Haifa Wehbe’s Tears” and “White Women Dancing”, a car door casting a shadow on an ornamental fence captioned مساء الخير a cup of shai arabiyy against red roses plucked from teta’s daily صباح الورد WhatsApp messages—packed with cultural semiotics that seem coughed up by the algorithm, Libyan-American artist Tasneem Sarkez’s work could be mistaken for AI. But that’s the point. They’re “algorithmic still lifes”, as she puts it.

“They’re not fruit in the basket; it’s more algorithmic with how we as people face the internet every day and interpret images,” says the 22-year-old New Yorker. While convincing, Sarkez’s artistic precision betrays the hyper-memetic image, truncating the speed of the scroll with an oil-painted glitch in the system.

Often playing with the aesthetics of promotional culture, the recent NYU graduate tows the precarious digital-physical, the politics of amusement, and her lived experience as an Arab woman in her first solo show, White-Knuckle, at Rose Easton Gallery in London. “I developed this sense of wanting to relay imagery that spoke to an aspect of the commercial product and leveraging that into cars, beauty items, perfumes—things that felt like they placed themselves as identifiers of Arab culture,” she adds. “But also, how they’re made and composed in this kind of meta way is something that can be read universally.”

London. Photography by Jack Elliot Edwards

Originally published in Dazed MENA Issue 01 | Order Here

The title of the show itself is a study in tension. “White knuckling is when you grip something so tight, like a steering wheel or a roller coaster, that your knuckles turn white, and it’s either out of anxiety or excitement,” she explains. The hyphen in the term holds the traction between both states, mirroring the perpetual unease of existing within today’s endless cycle–where anxiety for the crashing world order increasingly mixes with the strange amusement of its virality and spectacle fed by an interminable flood of content.

Much of her research begins with cars, a recurring fixation for Sarkez. “A lot of my work centres around the industry of car mechanics as it’s identified with pop culture and specific things to Arab aesthetics,” she asserts. “My mind just kind of framed the show to think about the tension that exists within the industry and the audience, then thinking about power as the main facilitator of that exchange.”

In one painting, “G-Class Dancing with the Shah”, black stiletto heels stamped with the Mercedes logo tell the story of how the G-Class, or G-wagon was developed in 1972 at the suggestion of one of the brand’s major shareholders, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (i.e., the Shah of Iran). Initially designed as a military vehicle, it soon became a civilian car. She jokes at the G-wagon today as a cliche status symbol: how white girls drive to Erehwon to pick up overpriced smoothies in a disguised army vehicle fit for a shah. Cataloguing how the G-Class became the vehicular equivalent of a Balenciaga city bag, I’m similarly reminded of how the Toyota Hilux became a ubiquitous symbol of modern warfare starting from the late 1980s on the Chad-Libyan border. Two ends of the same coin, cars are one of the most universal signifiers of status, global commercialism, and militarism, often becoming a lens through which to see how each overlap.

G -Class dancing with the Shah, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Rose Easton, London. Photography by Jack Elliot Edwards

Treating them as an entryway, Sarkez extends her commentary on the garish intersection of politics, amusement, and advertising ephemera beyond cars. In “First Lady” (2024), she paints a paparazzi image of what American media called the “Amazonian” female bodyguards of Muammar Gaddafi, juxtaposed with references to the text and packaging of skin whitening and virginity soap.

“The painting about Gaddafi’s women bodyguards is definitely a lot about the power of how they were perceived,” she says. “It’s a weird phenomenon—here’s this group of women paraded by a dictator, but then they’re some of the best-trained military women in the state, and they define gender norms in that way,” she explains, throwing the binary between the masculine and feminine under scrutiny. “But then, at the same time, there were crazy rules for being one of them. The craziest one was that you had to be a virgin. So in those paintings, I paired text from soap packaging – virginity soap, skin-bleaching soap – playing with the language of products that sell you this idea of being ‘pure’.”

There is dual violence at play here: the soldier as a harbinger of material and political force and the simultaneous sanitisation and commodification of the ideal woman. Two distinct yet intertwined manifestations of power collapsed into a single image. Referencing the American paparazzi’s glamorising and over-sexualising of the bodyguards, to some extent, evokes the US-Israeli military-entertainment complex and its rise of the ‘E-girl soldier’. Meanwhile, in another painting, the ever-patriotic bald eagle infiltrates a house key, becoming a canvas for dissecting Americana. “If you want your house, you will enter with the grace of the bald eagle and the American flag greeting you,” explains Sarkez. “But that is very commercial in itself,” she continues, asserting how Americana, more than a geographic entity, is an ideology packaged, marketed and sold in a belligerent cycle.

Unsurprisingly, the artist readily explores how Arab culture negotiates with the wholesale imperial export of America and the West in general. For example, one of her sculptures riffs on bootleg perfume bottles that she found on walks in predominantly Arab neighbourhoods in Brooklyn, Edgware Road in London, and then at home in Libya. She laughs as she recalls stumbling upon one bottle labelled “Obama”, which claimed to capture the scent of the former US president.

Elsewhere, her fascination with drifting culture – or ‘drift core’ – offers another compelling take on Western soft power. “All these cars are imported, too, and [in drifting] becomes this moment of wrecking the object of the West,” she explains. “When I was in Libya, seeing people do doughnuts in the street regularly—there’s something about that experience with the car and the freedom, the speed that’s met with that white-knuckle anxiety, of being kind of on the edge that young Arabs love.” I wonder, along with Sarkez, if we Arabs are accustomed to white-knuckling more than others. How much we might devoutly straddle the axis of anxiety and excitement almost as part of our DNA, imprinted from generations of political yo-yo-ing with the future tense. Never knowing how well our livelihoods will stick or sway at the behest of empire’s power, long before the doomscroll of the 21st century.

Sarkez’s work is very much a refusal of mythmaking around the Arab

experience, particularly one that creates “a specific image of pastness” where Arabs are “not allowed to move forward” nor able to claim a future. In response, she’s creating an archive of the Arab present. “I’m excited to continue to make work that feels like it’s archiving the most present moment we’re in,” she says.

While her subject matters are universally understood, some parts of Sarkez’s work are left untranslatable. The Arabic words are morsels decoded by native speakers alone, and the niche cultural references are treasures she doesn’t bother to answer for. She won’t apologise for her Arab reality; she actively asserts it. “The proclamation of the image for Arab people is not granted, nor is there safety in proclaiming it to the world,” she says. “But Arab people,

coming from the politics that we’re from, being on the edge of something, of white-knuckling—that momentum drives a lot of the work and is also the inspiration for so many Arab creatives of this generation.”

Originally published in Dazed MENA Issue 01 | Order Here