Posted in

Life & Culture, archive

Posted in

Life & Culture, archive

Aapne: Diasporas and the early internet

Text Afzal Khan

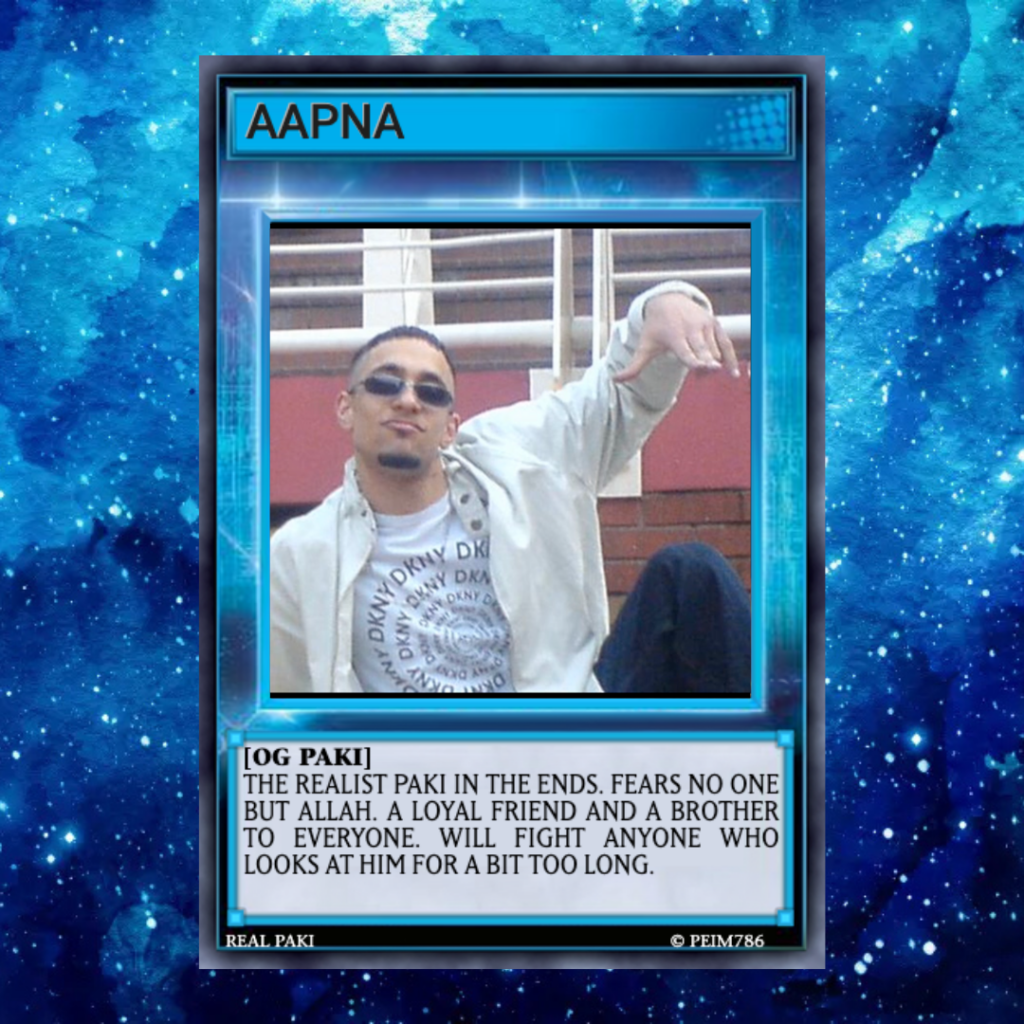

AAPNA: OUR OWN, ONE OF US PLURAL: AAPNE AAP·NEIGH

As a proud Bradfordian who spent the first 18 years of his life trying to escape Bradford, I have grown a certain affinity to the place I now call home. Bradistan, as it’s commonly known, is a complex city, but mostly a dull one. I’ve always described it as a city that feels like a small town. A city marred with a sordid history of race riots in 2001, regularly demonised by the media for being a hotbed for crime and the cardinal sin of not being white enough. Once a land of opportunity for first-generation migrants, later became a graveyard of the once bustling industrial North. Abandoned mills litter the hilly city, bricks blackened by the miasma of smoke that once clouded its skyline.

I wanted to capture the nuances of growing up in the West Yorkshire city Bradford, undoubtedly an experience that was mirrored in Pakistani diaspora communities across the UK. Late at night, I trudged through hundreds of inactive Facebook accounts in search of images that embodied the aesthetic I had grown up with. The grainy photos brimming with youthful exuberance and a kind of fervour that only a sense of carefree bliss would allow. My search took me to corners of the internet that likely had not been traversed in decades, as I blew the dust off of ancient YouTube videos with such low quality, they were almost unwatchable. Savouring the late-night nostalgia of these rabbit holes was a healing and somewhat poignant experience. A life and time I hadn’t thought about in forever, which I look back on with a kind of nostalgia and longing.

The early internet was a transient space that offered infinite possibilities and brought about a radical shift in self-expression. The internet is in many ways an unofficial archive for the human experience, as it had a kind of democratising effect on how many marginalised communities chose to show the world who they were, outside of toxic media narratives. This was the beginning of what has been referred to as the era of self-digitisation, where it became possible for a simulacrum of the self to be uploaded to the internet in a Matrix-esque fashion. This was also the beginning of what would become the present-day AI-fuelled dystopian nightmare we’ve created for ourselves.

While the first generation of migrants relied on photo studios to capture stoic images of their new lives in Post-war England, often posing with radios and household objects to showcase their social standing, later generations were documenting their lives in radically different ways. In the early 2000s, during the early days of the internet and the advent of cheap, mass-produced digital cameras, there was an opportunity that had never been available prior. The access to the internet allowed 2nd and 3rd generation migrants to harness the power of photography on newly formed social media platforms like Myspace, Bebo and Facebook to share who they were and how they wanted to be perceived. Teenagers in the inner cities of the UK were expressing themselves in the post 9/11 world with group photos, gang signs and self-published rap songs. They were uploading what would now be described as a dump, of 30+ grainy images to their Facebook account as if to shout “I exist!”. This was the modern answer to the caveman paintings of old, an attempt at cementing one’s permanence in the fleeting haze of modernity.

In the freewheeling milieu of working-class inner cities, South Asian youth turned to American hip hop culture in a spirit of familiarity. Evenings spent in dimly lit carparks, freestyling to Tupac instrumentals playing on a Samsung D500, deeply stirred by the words of the American rapper. The African American experience has forever had parallels with the experience of minorities in the UK, with similar forms of disenfranchisement. The youth were discovering shared meaning in Tupac lyrics and gorging themselves on American culture with classics such as Scarface and The Godfather. Tony Montana and Don Corleone pictures littered bedroom walls, t-shirts and Facebook profile pictures, as they told each other that “the eyes never lie, chico”. This was prior to the phenomenon of the Influencer and all the pompousness that surrounds it. There was no algorithm that needed to be catered to and no perfectly curated, aesthetically pleasing Instagram feeds, but rather teenagers loitering in city centres, taking group photos with gang signs. A brotherhood forged on the folly of youth and a love of rap, bassline and cars.

They could for the first time control the narrative on how they chose to be perceived in the tumultuous climate of the post 9/11, War on Terror era, in the shadow of the racial tensions of the 2001 Bradford Riots. Brown men and women were undoubtedly villainised by mass media outlets and faced discrimination in various ways. Through the power of the internet and its democratising effect, they were no longer delinquent youth or potential criminals with violent tendencies, but rather they were aspiring rappers, graphic designers and sound engineers trying to create music and art that spoke to their experiences.

This research culminated in the archival photobook I have aptly named Aapne, which is an homage to British Pakistani youth. Aapne means “one of us” in Pothwari/Punjabi. I created this archive to capture that feeling of youth and endless possibilities as a kind of totem for later generations who never saw this side of the early internet. It is an homage to the diasporic mess that many second-generation migrants found themselves in at the turn of a new century and how they traversed its complexities.