Posted in

Art & Photography,

Posted in

Art & Photography,

Somnath Bhatt and Gabrielle Sicam reflect on Republic Of Shadows at GALLERYSKE, New Delhi

Text Gabrielle Sicam

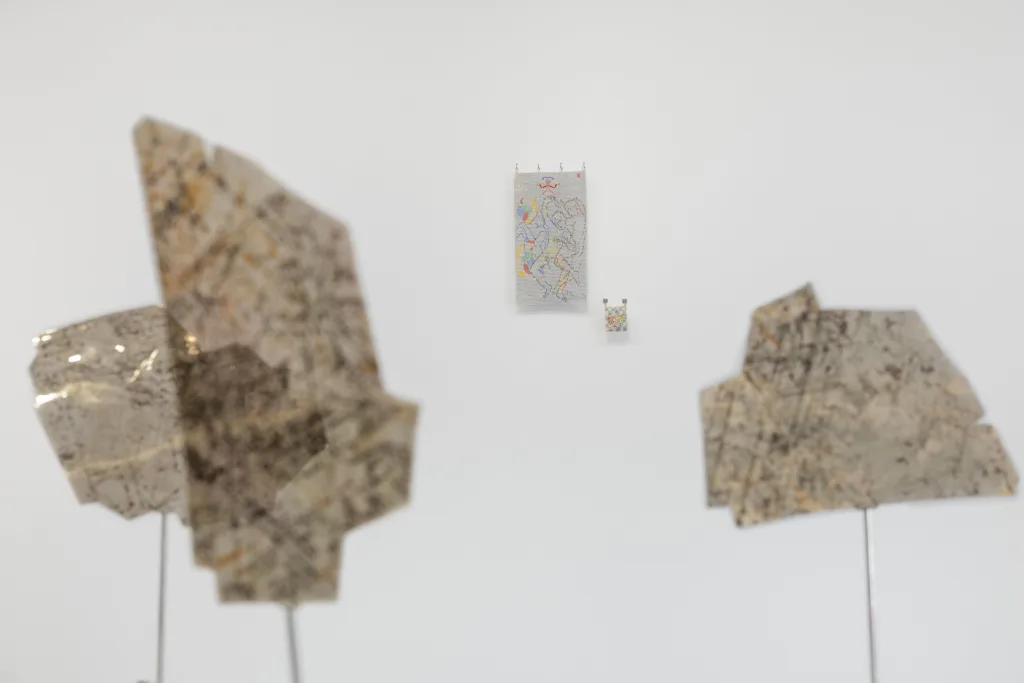

Somnath Bhatt’s latest exhibition, Republic of Shadows છાયારાષ્ટ્ર, at GALLERYSKE in New Delhi, eludes all assumptions of linearity. Based between Ahmedabad and New York, Bhatt’s art develops his interests in slippage and in/articulation into a peripheral multimedia language. In the spirit of his fervent, exploratory pieces, I tried to ask Bhatt questions that would prod and provoke, hoping to communicate the joy of going through his profound body of work.

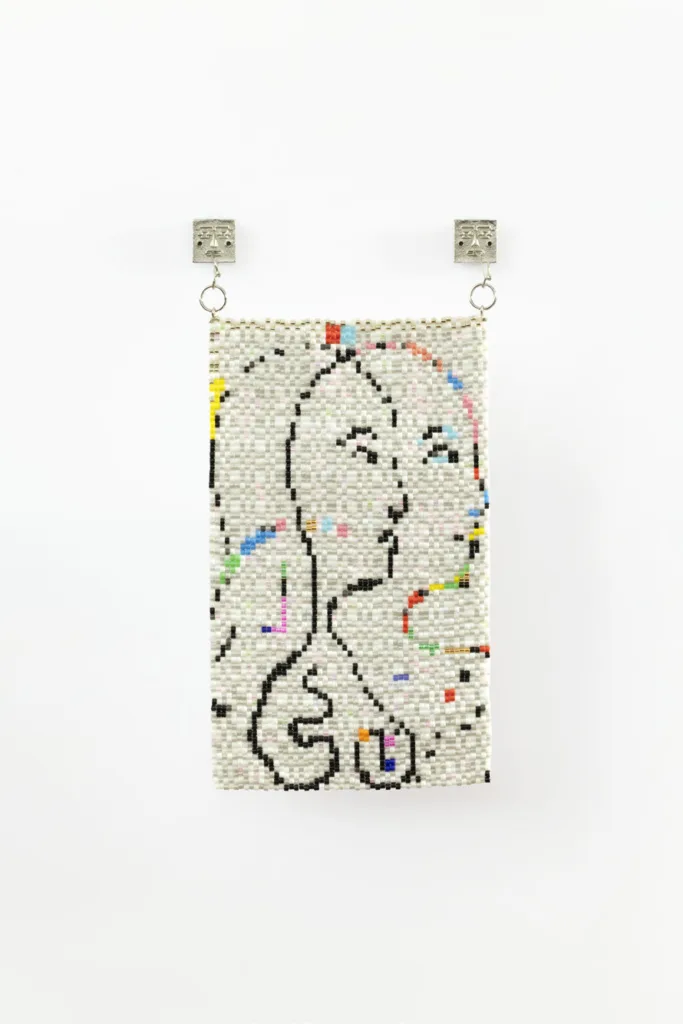

Gabrielle Sicam: As someone who is a bit more familiar with your pixelated drawings and design work, I found your use of different materials and technologies in this exhibition really interesting. I especially loved the Miyuki beads in the HOLD pieces, offering tactile analogues to pixels and processes more reliant on machines e.g. risograph print. I’d love to know more about this tendency in your work and how you go about exploring new materials and technologies day-to-day.

Somnath Bhatt: The materiality helped push the work beyond the familiar conversations around its so-called ‘techno-mythic’ qualities is a framing I find very limiting. Yes, the work is pixelated; yes, it references esoteric looking non-western imagery sometimes. But that is not where it starts or ends. The materials, and the ways they are handled, open up questions that are more nuanced, tactile, and pleasurable to engage with. Questions of time, tension, opacity, orientation, of looking and then looking again, of the work actively demanding attention. These materials refuse to stay still. Even in photographs, the works cannot be fully grasped in their totality: they are iridescent, polychromatic, dichromatic, metallic, tinted and shimmering. They can only be experienced in motion while present in front of them. This feels more expansive than reading the work solely through the lens of “digital ruin,” allowing the conversation to move toward how meaning is built, held, and transformed through physical engagement and presence as much as through technological display of pixels.

GS:In the spirit of the works’ psychoanalytic elements, I want to know about what kind of artist you were as a child, if you were at all. Were you doodling at school? Were you collecting objects?

SB:I was told that I used to draw, even before I learned how to speak.

I drew all over my grandmother’s walls with my cousins, overlapping wild animals – forests, jungles, strange figures, and scribbled creatures tangled all across her crumbling calcite surfaces of her bedroom walls.

GS: You spoke a bit about myth and the perception of myth in your work in your interview with The Creative Independent. You also spoke about the misuse of myth, which is especially apparent in the Cartonnage diptychs. Tiger Dingsun writes about the misappropriation of Harpocrates across mythologies. You place two interpretations of Harpocrates on the same wall, connected via the branches of a tree outside of the gallery. Do you attach a kind of responsibility or sense of importance to that reconciliation?

SB: When I speak about myth, I am less interested in myth as origin and more in myth as movement: how stories travel, fracture, and are re-inscribed. Placing two interpretations of Harpocrates on the same wall is not an attempt to resolve those tensions, but to hold them in unusual proximity. I was pleased to see this multiplicity emerge historically through a collective unconscious, because part of my methodology rests on seeing and asking what happens when a metaphor or a symbol is twisted, obscured, misplaced, or lost as it moves through many worlds.

If there is a sense of responsibility here, it lies in refusing singular narratives. Rather than reconciliation as closure, I am interested in coexistence and allowing contradictions, misuses, and overlaps to remain visible, unresolved, and therefore open to continual transformation. The work insists on the fact that there are, and will always be, many Harpocrates: multiple figures shaped by contexts, powers, and desires. In that sense, the work asks for attentiveness rather than agreement. A recognition of how easily myth becomes a tool for controlling and gripping the present rather than deepening or illuminating it.

GS: A follow-up: as an artist interested in the unconscious do you feel like a custodian of it in any way? Do you feel like work that channels that transcendent quality is rare in contemporary art, or is it that we as observers are just not looking closely enough? Is there even a sense of loss of the unconscious at all?

SB: What draws me to the unconscious is precisely its refusal to behave. It’s polyvalent, visually unstable, contradictory, and disobedient. It doesn’t offer coherence; it knots or flips meaning inside out. In that sense, the unconscious feels like a shadow holding a knife to the throat forcing our attention onto something undeniably urgent about our present condition. I wouldn’t describe myself as a custodian of the unconscious. That suggests stewardship or ownership, and the unconscious resists being held in that way. I think of my position as one of exposure. The unconscious isn’t something to hold; it’s something that keeps insisting, often uncomfortably, on being noticed.

I don’t think the unconscious has been lost. If anything, it’s become harder to tolerate. This paragraph by Mark Fisher from K-PUNK comes to mind:

“It is imperative that we carve out some spaces beyond the hyper-bright instant. This instant is insomniac, amnesiac; it locks us into a reactive time, which is always full (of outrage and pseudo-novelty). There is no continuous time in which shadows can grow, only a time that is simultaneously seamless (without gaps; there is always “new” content streaming in) and discontinuous (each new compulsion makes us forget what preceded it). The result is a mechanical and unacknowledged repetition. Is it still possible for us to cultivate shadows?”

GS:I imagine that there are a number of viewers who are very interested in the knowledge-work of observing the art and ‘decoding’ the figurations. Is the end-goal a cult of people who will do the work to ‘get it’? Or is it, I suspect, less cynical? How do you avoid or address the elements of esoteric or ‘myth’-art that tend more towards exclusivity?

SB: Haha not at all. I’m not interested in creating a hierarchy of understanding, or rewarding those who can decode references correctly. If anything, the work resists closure; it doesn’t resolve into a single reading, even for me. The more you lose yourself, the better. Esotericism becomes exclusionary when it promises access to a hidden truth. I’m more interested in shared uncertainty. What is not yet imaginable often summons older forms — myth, ritual, inherited structures — not as answers, but as pressure points. I’m less interested in moving forward, I am interested in stepping sideways. The elements of esotericism or myth I am interested in are movements, not ‘world-building’. So to me it feels analogous to like time-traveling via shuffling a playlist. Stretching or unsettling our usual frame of imagination and reference. The intention of the work is to let viewers encounter images and objects that feel familiar, only to have that familiarity slip — moving in and out of recognition and into something unknown. When you no longer know what you’re looking at, you’re forced to contend with silence. That silence becomes a mirror of something I couldn’t place. The deepest captivation occurs when a viewer senses: this wasn’t made for me — and yet it found me

GS:I get an eroticism from your art, not just in depictions of figures in sexual or romantic acts. Tiger Dingsun mentions ‘the libidinous nature of knowledge’. I’m reminded of Peturpitus, another contemporary artist who combines unexpected figurations and layers to unearth a kind of erotics. How do you think fulfilment – of knowledge, or of a more cathartic kind – might play into your work and the interactions people have with it?

SB:I am delighted you sensed that dimension. There is an undeniable erotic charge in difference and contrast, in what does not immediately align or open up. For me, eroticism is not about a direct want or depiction but about minute attention — the kind that sharpens when one notices the smallest shift: the flick of a wrist, the slant of an eye, a pause, a tremor in the lip, the breath that follows a heavy sentence.

In this sense, I am drawn to how desire operates not as fulfilment but as friction. Drawing on Daud Ali’s Courtly Culture and Political Life in Early Medieval India, power itself can be felt as something approached through eroticism rather than command. Authority is courted, admired, tended to and even ‘desired’ to be able to be interfaced with. In this framework ornament, refinement, sensuality — these are not decorative additions but active forces that shape identity, allegiance, and operations in the presence of political power. Erotic sensibility, then, is not peripheral to structure or power; it is one of the most precise ways through which they become visible. Crucially, the figure of authority is repeatedly addressed as a lover: courted, admired, desired, so that power itself is approached through intimacy rather than obedience. Desire sharpens attention by destabilizing it, making meaning felt before it is known. Desire becomes a site of encounter where attraction, threats, discomfort, and curiosity coexist. Read this way, courtly cultures and their echoes in other literary traditions become where desire and vulnerability are encoded through refinement, often carrying homoerotic tension. Many of the figures I draw wear elaborately ornate, imagined courtly costumes poised in a state of ambiguous grace. Erotic sensibility, then, is not peripheral but instrumental; it reveals structures of power as clearly, and sometimes more incisively, than overt political acts.

In my work desire or the erotic are not an image but a condition: a sustained closeness, where forms dissolve just enough to remain present, forms shifting with your shift in posture, withholding completion. Touch is implied through looking, and desire emerges through delay.

GS:I’d love to talk about your mural with Ayed Arafeh at the Wonder Cabinet in Bethlehem, Palestine. I understand that collaboration has always been part of your work. What was the process of collaboration like for the mural, and how did you retain, or build upon, your initial ideas for the mural throughout the process, especially considering the political significance of the space?

SB:In all honesty, the process with Ayed was largely playful and formal — a back-and-forth of images, drafts, and ideas. It felt like making a drawing for friends. I was genuinely thrilled that Youssef and Elias Anastas thought of me for the mural.

When the mural finally came into being, the western imagination had become both hyper-fixated on Palestine via the lens of tragedy and pity and, paradoxically, hyper-avoidant of engaging with it via the lens of censorship and fear. That tension was very present, but it wasn’t something we tried to illustrate directly. Instead, the work held onto its original logic: collaboration as a way of thinking together, of allowing forms to emerge through exchange rather than declaration or planning. Working in a space like the Wonder Cabinet carries political weight, but the responsibility for me was not to instrumentalize it. The work doesn’t aim to overwrite nor aestheticize the politics of the site.

At the opening of the mural Wonder Cabinet in Bethlehem, there was a moment that felt more beautiful than the images themselves: @malak.bannoura played on the qanun a Gujarati prayer (પ્રેમળ જ્યોતિ તારો) weaving sound, language, and presence into the space.

GS:As a writer, I would love to know about any literary influences that contributed to your work. As someone compelled by the textures and polyphony of this exhibition, I’d also love to know about any musical or otherwise sonic influences.

SB: Literarily, The Same River Twice: Notes on Reading, Time, and Translation by Saskia Vogel was genuinely transformative for me. The essay reflects on years Vogel spent translating Ædnan from Swedish into English, tracing how texts, translators, and readers are all altered by time. That sensitivity to drift, to temporally layer, and to address meaning as something shaped by duration and change rather than mastery or authority resonates deeply with how I try to think about visual form in my own work.

I was also really inspired by how Rick Owens writes about his collections under every video on his youtube channel. His language is visceral, and declarative. It commits. Personal memory, myth, material process, ethics, and excess all sit on the same plane, stated with equal intensity.

Sonically, I was drawn to: the Telugu love song Sada Nannu and the qawwali Kanhaiya Yaad Hai Kuchh Bhi Hamari by the deccani poet ‘Hilm’ which are both intensely melismatic, almost splashy in their sonic excess ; thick with emotion and drama. Sada Nannu lingers in the otherworldly sensation of falling in love for the first time, while the qawwali carries a deep existential ache, addressing a lover coded as the divine and asking, with painful desperation, whether he even remembers having ever met you.

My fascination with radios crystallized through the sparse, mechanical textures I encountered in Dajuin Yao’s Dream Reverberations 夢的殘音 on UbuWeb, and later through Sega Bodega’s I Created The Universe So That Life Could Create a Language So Complex, Just To Say How Much I Love You. These works feel grainy, stripped-back, almost geometric much closer to signal, pattern, and overflow of structure.