Posted in

Art & Photography, Exhibition

Posted in

Art & Photography, Exhibition

Faiza Hasan on collective memory and history in her latest exhibit

Text Dee Sharma

Indian visual artist Faiza Hasan’s Hifz is a deeply interpersonal exploration of memory, identity, and the passage of time. The exhibition presents a folio of charcoal sketches drawn from found images, those tucked within family albums, unearthed during a deep clean of a home, wedged in the crevices of wardrobes, or slipped between the sleeves of forgotten books. Alongside these, Faiza exhibits delicate embroidery on rice paper. Yet, it was the charcoal works that captivated me most, sketches saturated with motifs of personal history and memory, at times feeling almost too intimate to witness. The experience evoked that uneasy familiarity of rummaging through someone’s handbag for gum, consciously averting your eyes from anything too private.

But that is the beauty of Hifz: it allows the deeply personal to seep into the collective consciousness. The word Hifz refers to the act of memorising the Holy Quran, an act of sacred remembrance. Faiza reclaims this process as a metaphor for preserving personal and cultural memory. In a time when systemic erasure of Muslim identity is ever-present across Indian society, her quiet resistance takes the form of recollection, gestures of tenderness and subtlety that resonate far beyond the self.

My conversation with Faiza unfolded over a fragmented timeline. The first point of contact was on the eve of her solo show, Hifz, opening at Gallery SKE in New Delhi. The second took place through a Google document I sent her after a failed attempt to meet in person. The third and final exchange, a phone call, ultimately gave this conversation its current shape.

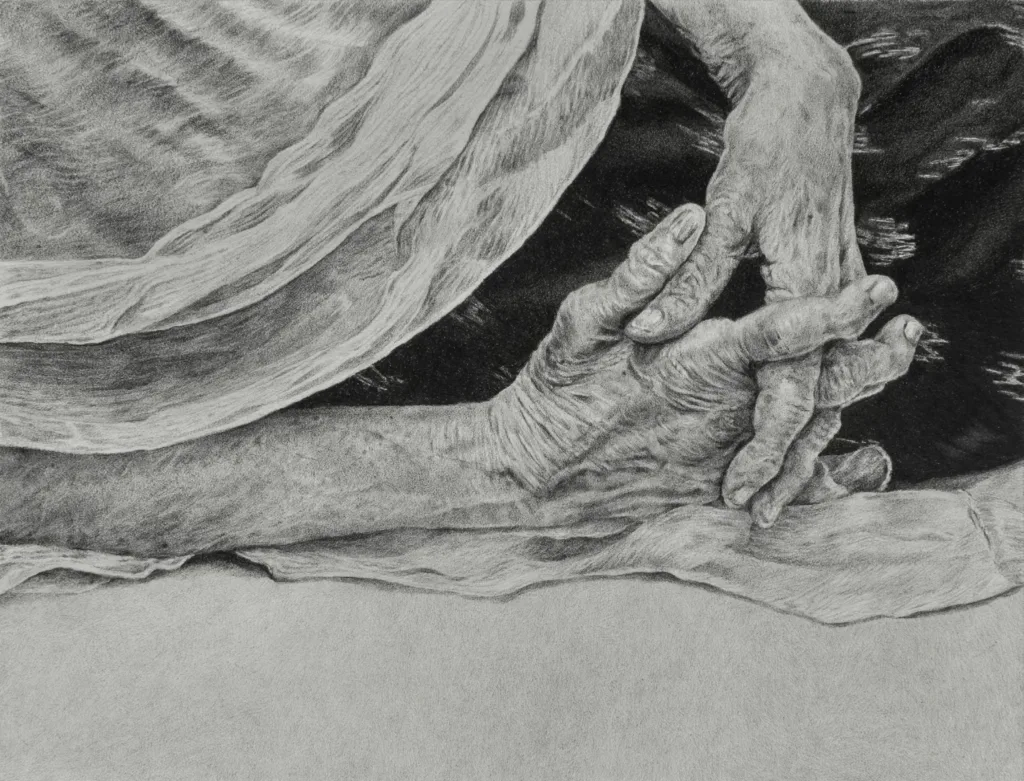

Dam

Charcoal on paper

13 x 17 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

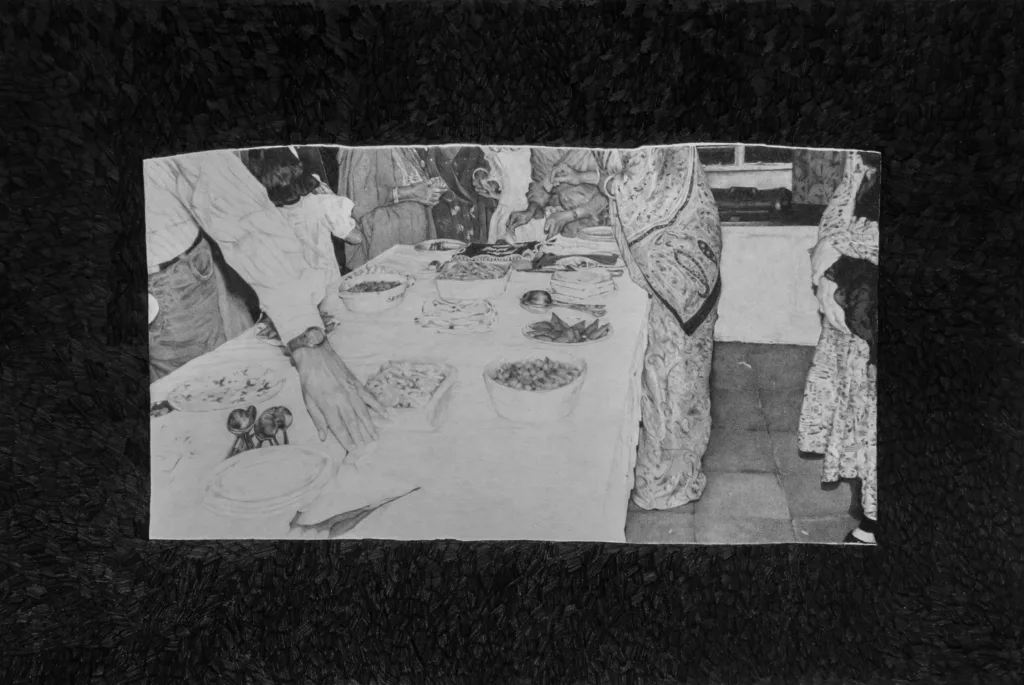

Barkat

Charcoal on paper

17.5 x 26 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

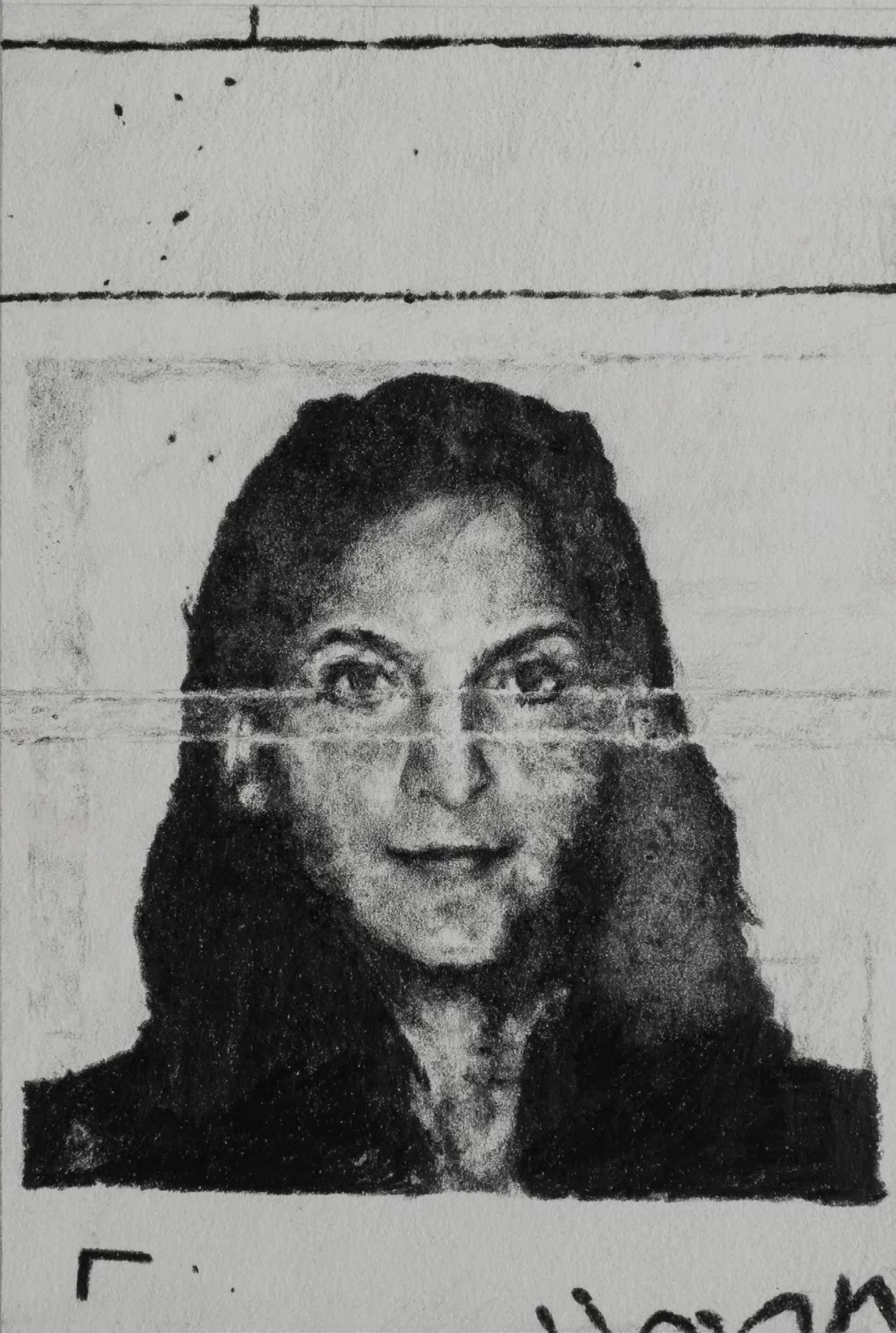

Nanima

Charcoal on paper

9 x 7 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

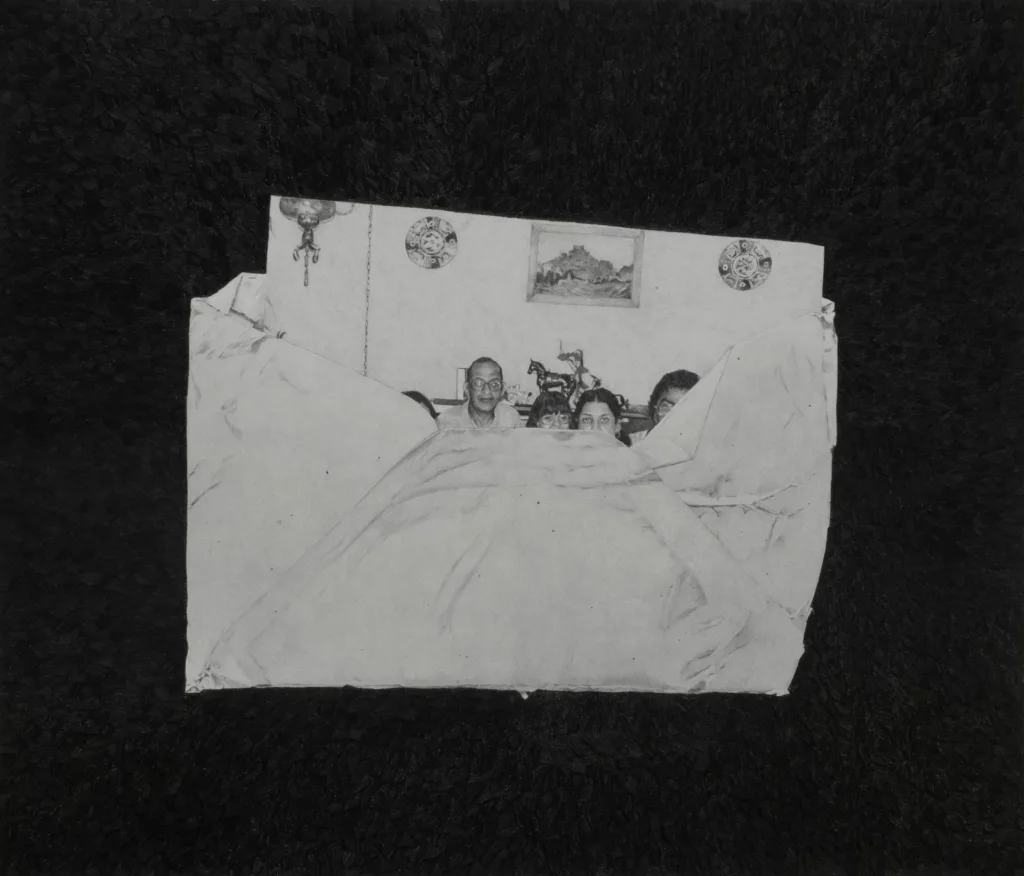

Qila

Charcoal on paper

17.5 x 20 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

Fern Hills

Charcoal on paper

23 x 18 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

AC Guards

Charcoal on paper

26 x 13 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

Nasr

Charcoal on paper

12.5 x 9 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

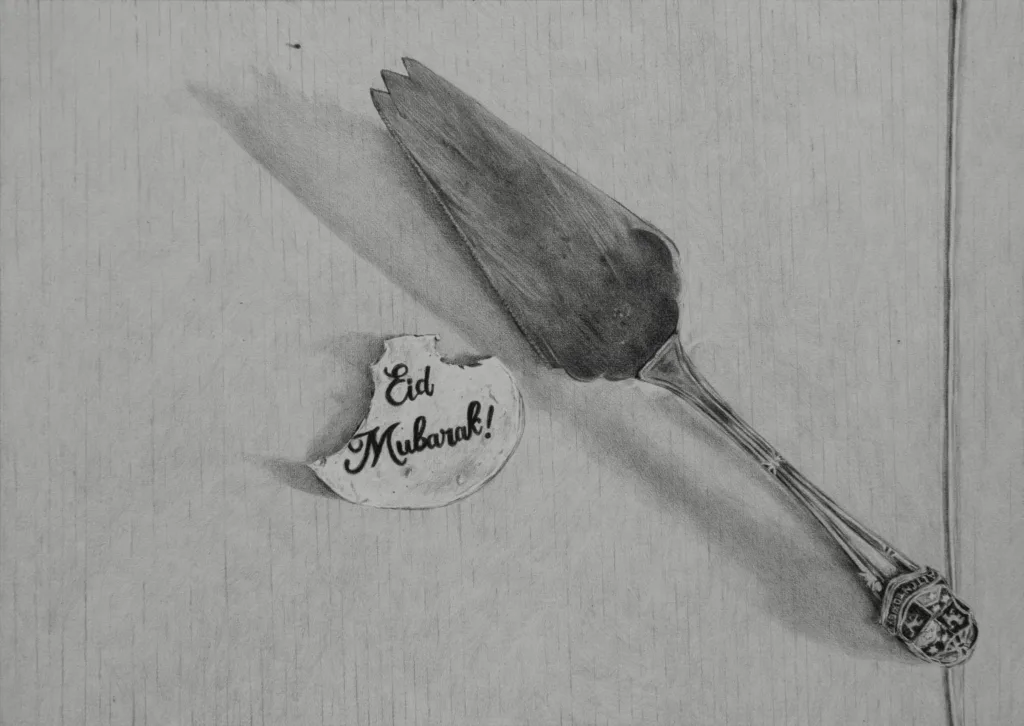

Eid Mubarak

Charcoal on paper

11 x 8 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

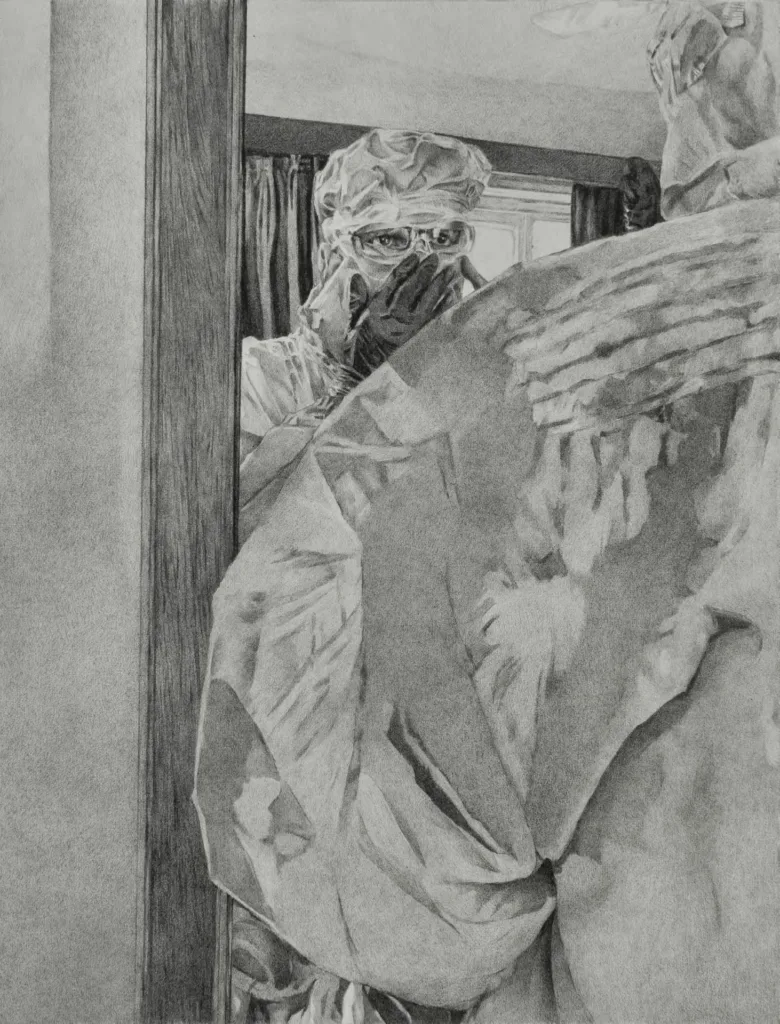

2021

Charcoal on paper

11.5 x 9 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

Kitaab

Egyptian cotton on rice paper

11.7 x 16.5 inches each

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

Photo credit: SV Photographic

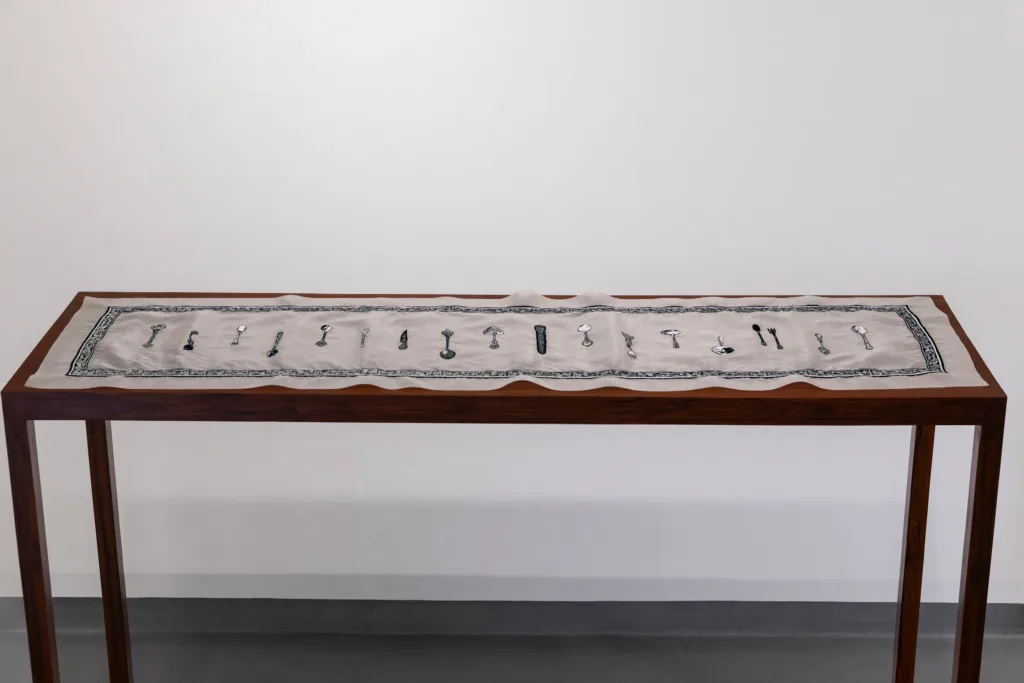

Dastarkhwan

Cotton on silk organza

63 x 22 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

Photo credit: SV Photographic

DS: A central theme that is present in your work throughout this exhibition is memory: collective memory, found objects, and preserving memories. The works on display act almost as a counter to what Susan Sontag posits of collective memory, undermining personal archives to build upon a collective awakening of identity and presence. How do you think your uncovering of personal lineage and memories of the mundane can help imagine a more objective version of collective memory?

FH: Dear Dee, it’s interesting how you’ve posed the question. I’m going to try and work through my thoughts here, through my process, and how I think my work functions/ could function.

To begin, so much of my interest in objects of personal history lies in how these remain entangled with the larger, more prominent events of their time. And in examining them in the context of the present/ as a way of contextualising the events of the present. Furthermore, in my practice, I am also interested in how images function— their ability to shoulder complex narratives, to converse with other images/ objects and the manner in which these can be incredibly evocative.

I think of objects of personal history as portals to ideas, imaginations. Working on intricately detailed drawings of these objects and photographs, that often take weeks or months to realise, is also a process of looking (and in due course compelling/ inviting others to look). It necessitates a keen examination of details embedded in what are originally rather small images— sometimes but shards. Details such as objects, gestures (of touch, for instance, of being held or simply being in proximity to others), patterns, textiles, food. Details that can be prompts to remember/ recognise, that can evoke shared/common experiences(and even conversations, connections) that can help us reflect on collective memory, potentially also in more objective ways.

A lot of the material that I work with exists between what is personal, public, official and even the mundane. Photographs along with letters, documents, recipes and found objects allow for imagining/ building broader contexts. And these can be both— a counterpoint to more dominant narratives, especially those that seek to flatten or invisibilise the ones that don’t fit within their framework/ intention, but also a rich (and intimate) appendage/ lens to look at larger historical/ socio-political narratives.

Dastarkhwan

Cotton on silk organza

63 x 22 inches

Image courtesy: GALLERYSKE and the artist

Photo credit: SV Photographic

DS: We often experience time less as isolated years and more as eras defined by cultural shifts and collective change. Has a particular way of interpreting time shaped your work, and how do you personally experience its passage?

Do you find yourself relating to time more through memory, anticipation, or the present moment? In your creative process, does time feel like it expands, compresses, or even disappears? Do you feel your sense of time is guided more by personal milestones or by broader cultural events?

FH: I prefer to navigate the idea of time through non-linearity and relationality (moments in time/ memories existing in relation to others that may or may not be related chronologically). And also think of my creative process as a way to weave through objects and images from the past with those from the present. There’s a back and forth/ push and pull between photographs and objects that belong to a different time and those that I continue to document and collect.

There are also gaps. Gaps that reside both within and between memories, and gaps in the imagery of my drawings— particularly where photographs are torn or faded. Both kinds have become an important part of my creative process and visual vocabulary.

I also think that one’s sense of time can be an entanglement/ sometimes even an enmeshment of both personal milestones and broader cultural events. Often times it is difficult to separate the two and look at one entirely on its own without the other looming close by. And when working with/ thinking about objects (for instance, spoons that I collected as a child), I find that each has its own unique history and context, but each also becomes a very particular marker/ memory in the trajectory of my own life/ personal history.

DS: Which also leads me to a thought about how your work is also an archive which defies antiquity. It exists as a living process which is ongoing. You’re archiving the present. What do you think of archives? Are they places for memories to gather or perhaps sites of reimagining history?

FH: I like to think of archives as fluid spaces. Spaces that continue to expand and expose many interconnections as they do. For me, they’re both repositories as well as spaces to draw out, trace, and expand from.