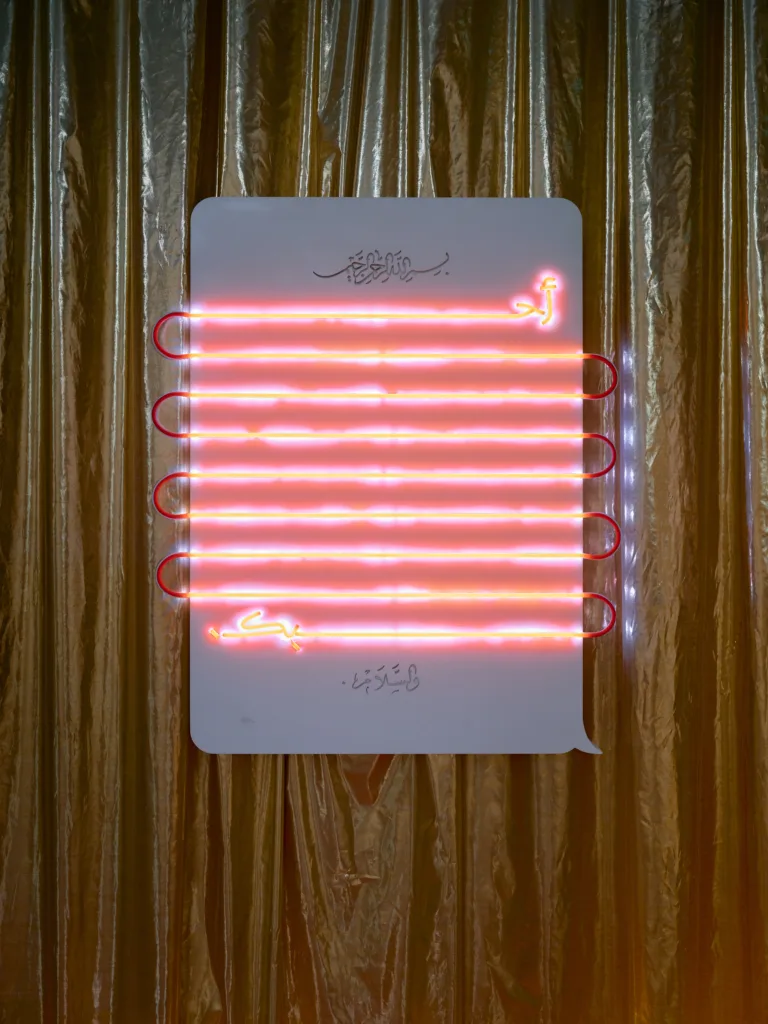

Aziz Jamal, Hearts, bear witness, Courtesy of SAMoCA at Jax

Posted in

Art & Photography, Dazed MENA

Aziz Jamal, Hearts, bear witness, Courtesy of SAMoCA at Jax

Posted in

Art & Photography, Dazed MENA

Wedding-Core: SAMoCA’s retelling of MENA’s marital maximalism

Text Mariya bint Rehan

While marriage as an age-old institution is facing threats on all global fronts, the charge against a tradition seen by many as ungainly, irrelevant, and perhaps too friction-addled, is facing finer, much more intrinsic tremors in MENA. As we see marriage rates plummet in much of the global north, a trend detected as early as the seventies in America, our tendency to look to Western frontiers as cultural and moral harbingers – and indeed arbiters – means there is this faulty and telling expectation that the rest of the world will follow exact-suite. This is partly why SAMoCA’s A Night of a Lifetime, in Diriyah’s Jax district – an exhibition which explores the rituals and gestures surrounding marriage in the region – appears predictable but disarmingly endearing at the same time, much like marriage itself. The meta themes of the show do not end there – an unabashed celebration of kitsch, performance and ritual, it is impossible to visit without feeling a sense of juvenile anticipation, a feeling that is all the more stark in an era of digital-aloofness and which has rendered monocultural events extinct. It’s colours and textures evoke an almost primordial excitement for the cultural feast that is the marital union – over and above love itself; that imagined space that love supposedly graduates into that is, despite itself, also becoming increasingly elusive and spectre-like for young people in the MENA region, for whom marriage is no longer an inevitable outcome.

The exhibition showcases the friction between the public domain of celebration that we all share and engage in, versus the private confinement of the relationship itself – and the simultaneously outward and inward nature of marriage – through its very enveloping architecture. A theme that is particularly relevant now in a digital era of soft launches and digital panopticons, where young Arabs are carving out a space between the culturally acceptable and unacceptable on digital terrain. The gallery welcomes you in, granting you the keys to a space that evokes that eerie sense of spectatorship; you feel both included and strangely intrusive at the same time. This perfectly executed gothic sense of domesticity, highlighting simultaneously the familiar and strange, enables us to defamiliarise a ritual we all have an intimate affinity with, perhaps with a view to reimagining it on new terms.

Much like the marital relationship, the show is split into two opposing sides, one which depicts the tragedy of marriage and another which showcases its joy. The garlanding feature of the tragic is a feasting table installation by French artist Nicolas Henri, Yasmine and Khalil, The Story of a Love Encounter, in which the bride and groom are laid out on the banquet, ready for public consumption, while a detritus of ornately framed images decorate the low-lit wall behind. The twee, collage-style images, featuring cut-out faces, fabric and jaunty composition, sit politely above. There is something quaintly European in this imagining of the banquet hall as representation of MENA marital celebration. It sits undetected, nestled in the broader exhibit in the same way our now-globalised expectations towards the traditions of marriage in the region do. A region, it must be said, which merits its own reimagining of the cultural powerhouse whose legs have carried it much further than its western counterpart.

Saudi artist Sultan bin Fahd’s To Dust is another striking contribution. Fahd’s artistic tendency to rewrite cultural memory, this time in the form of a great mass of broken and entangled chandeliers which appear to have crashed out on the floor unceremoniously, adds the right amount of performance and sobriety to a space which is designed to question some broader ‘unquestionable’ cultural approaches. The installation, rather than emitting, draws in the light, creating an overspilling spectacle of gratuity, poignantly contained in a golden embossed cage.

Kuwaiti artist Amani Al-Thuwaini’s ephemeral He Is Not Your Choice consists of a suspended veil embroidered with a narrative that speaks of a marriage shaped by familial expectations. It’s form sombrely mimics its message – the unassuming, almost indiscernible shadowy whisper that it casts on the floor tells the unspoken tragedies that culturally dogmatic approaches to marriage have engendered. The use of embroidery a welcome visual reference to Kuwaiti heritage, and historically female-led arts in the Gulf. It adds to a canon made up of a new generation of artists in the region that are refashioning the tools of legacy to tell their own stories, and therefore it gestures towards a kind of optimism for the future.

The gloriously kitsch, gold curtains which frame both sides of the exhibition create a continuity which emblemises perfectly the precarity between happiness and sorrow in marriage, and which tangibly drape the viewer in a kind of disorienting time warp. At once timeless and dated, they follow the broader theme of the exhibit, which recreates a kind of purposefully blind nostalgia for the cultural institution of the wedding, a cup we’ve all sipped from, from the earliest of ages. Wedding ceremonies are where culture expresses itself loudly and unapologetically, and where we as audience engage and canonise our culture with both the familiar and novel. The intimate, cultural proximity we all possess towards The Wedding creates an uncanny, endless constant in a world that is seemingly emptying itself of life-long partnerships, and purportedly generating less marital joy. It appears to be a safe space we want to safeguard, away from the sceptical tentacles birthed from an age of memes and more cynical cultural language and expression. You can’t help but feel cocooned in this wilful charade, and not thoroughly enjoy it at the same time, too.

In the celebratory chamber, a triptych of portraits by Moroccan artist Sara Ait Benabdallah act as an antithesis to the selfie – dressed in Lebssa Lkbira, the women in the portraits are formal, austere and uncandid. Entitled the Dry Land Series, the pictures speak of a bygone coming-of-age, where dress is extreme performance and the male gaze takes up the most space in the room. Noticeably unframed, their dishevelled presentation is a welcome departure from the staged nature of their content. Once again, the art gestures toward a previously physically and culturally restricting tradition that a new generation of spectators are perhaps able to revisit with a neutrality that comes from the ameliorating passing of time.

The central piece of the entire exhibition, Hearts, Bear Witness, is a surreal, AI-like, heart-shaped rendering of the ceremonial Kosa, cast in a Y2K baby pink, complete with exaggerated floral pillars as protective guards. Created by Saudi artist Aziz Jamal, it is simply crack for the eyes, feeding a visual appetite born from slop and the debris of an internet gone rogue. It is a perfectly satiating experience for an exhibition which invites us to unashamedly celebrate the celebration. It is the wedding-maxxing, MENA-core genre we never knew we needed. The cartoonishly dreamlike stage setting actually projects onto the museum’s façade, quite literally drawing you into the pageantry, inviting all the performative angst one might feel from a real wedding stage and further blurring those lines between reality and simulation.

The finale of this succession of artistic events is the fittingly opulent Le Trousseau by French Tunisian jewellery designer and artist Shourouk Rhaiem, which, as its name suggests, consists of a litany of domestic objects, though unexpectedly, encrusted with Swarovski crystals. Placed in a darkening chamber, Rhaiem intended for the changing effect of the light to convey the contrast between image and reality – the objects oscillate between the extraordinary and mundane, highlighting the contradictions perceived in domestic life. A fitting end to the exhibition, it calls into question the various changes in economics and gender dynamics, and broader feeling of disillusionment, that are leading the charge away from marriage, in very different ways and at different paces, both at home and abroad.

It creates an interesting juxtaposition with the exhibition’s greeting piece, Hoda Alnasir’s Make Some Noise, consisting of giant inflatable male figures that sit outside the exhibition building, complete with thaub and shamagh – a totem of the visibility of men’s ceremonies compared to women’s. In the quite literal private chamber of Rhaiem’s work, which represents female sentiment, we see the main drivers of the region’s trend in fewer marriages, an answer that you can glean if you look hard and deep enough.

A true indulgence of the senses, SAMoCA’s curation is the perfect homage to marriage in an imperfect world. Its eclectic pieces and dream-like compositions are the perfect celebration of our most idealised realm, where our personal and cultural aspirations and fears are projected. For such a contested space, the exhibition provides a refreshingly honest insight into the cultural nuances of marriage. It perfectly reflects the very human ways we commemorate the idea or image of love, our collective instinct to create entire world-forming structures around the speculation of one human emotion, and how it speaks of both the joy and tragedy it holds intimately for so many of us.