Posted in

Life & Culture, Anniversary

Posted in

Life & Culture, Anniversary

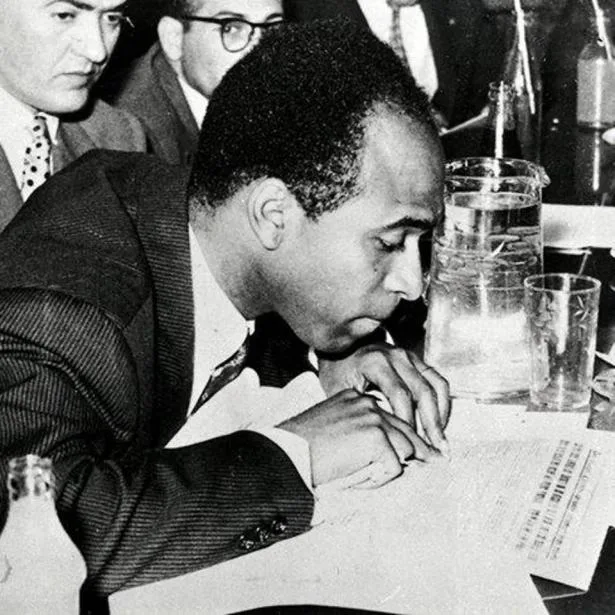

Frantz Fanon at 100: Speaking to a world still colonised

Text Hamza Shehryar

On 20 July 1925, in a hospital in Fort-de-France, in the French colony of Martinique, Frantz Omar Fanon was born.

By 1960, he had become a physician, a psychiatrist, a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN), and the author of some of the most searing texts ever written on the psychology of colonisation. That same year, he was diagnosed with leukaemia. He kept writing, devoting his final months to what would become his most forceful book, The Wretched of the Earth, which was published in 1961, shortly before Fanon died of the disease in a Maryland hospital, in the imperial core, at the age of 36. Decades on, his writings remain urgent, and his legacy endures.

A pan-African Marxist revolutionary, Fanon understood that dehumanisation wasn’t a consequence of colonialism; it was a part of its very foundation. His assessment was rooted in lived experience as a Black man in France and a psychiatrist in Colonial Algeria. In fact, while working as a psychiatrist during the Algerian revolution, he treated both tortured Algerian fighters and the French soldiers inflicting that brutality. These encounters – with the wounds of the oppressed and the pathology of the oppressor – would shape the raw, revolutionary force of his writing, which tore into the lies of empire and revealed how racism and cultural erasure were essential to its survival.

Fanon diagnosed colonialism as not only a political system, but also a psychological one. In Black Skin, White Masks, his searing 1952 study of the Black psyche in a white world, he explained how colonised people are conditioned to internalise their own oppression: to mimic the coloniser’s values, suppress their own cultures, and seek approval from those who deny their humanity. “The colonised is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country’s cultural standards,” he wrote. It’s a dynamic that still shapes cultural hierarchies today, in media, education, and the language of “modernity” itself.

Reading Fanon today, you realise how many of us, especially in formerly colonised countries, still shrink ourselves to appear “civilised” to the West. We disown our languages, mock our customs, and uphold whiteness as a mirror we must shape ourselves against. “The oppressed will always believe the worst about themselves,” he wrote. Fanon saw this not as an accident, but a psychological wound inflicted by empire. A wound that could only be cleansed by resisting through any means necessary, including violence.

“The colonised man finds his freedom in and through violence,” he wrote in The Wretched of the Earth, a study of colonial violence, the psychology of the colonised, and the revolutionary path to liberation. “This is not to be understood as a front against other men. Violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction.”

In Gaza today, where Israeli forces have killed at least 60,000 Palestinians in less than two years in an ongoing genocide, the West continues to equate the oppressed with their oppressors, condemning the threat of resistance more than the fact of genocide. Fanon saw through this logic. He knew that no form of resistance would ever be deemed acceptable. “The native is declared insensible to ethics; he represents not only the absence of values but also the negation of values,” he wrote. It is never the coloniser’s 2,000-pound bombs that are called violent. It is not the genocidal settler-colony that is branded a terrorist organisation. Those designations are reserved for non-violent direct action groups opposing it. And so, he advocated resistance, by any means necessary.

Naturally, Fanon also fiercely rejected colonial liberalism: the idea that reform, aid, or “humanitarian” intervention could make colonialism more ethical. He saw through the moral posturing of colonial powers, a legacy that continues today as states condemn “violence” while selling arms and shielding apartheid regimes. He was clear and uncompromising. You will never bring about change by appealing to the conscience of your occupiers, for if they had a conscience, they would not be occupying you.

In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon also warns that without dismantling the colonial state, the colonial rulers are replaced by elites from the native bourgeoisie, leading to new forms of exploitation under the guise of independence. He anticipated that decolonisation without radical restructuring would simply reproduce oppression under a different flag – something that has, unfortunately, come to define many post-colonial states around the world, where governments enforce neoliberalism, suppress dissent, and act as enforcers for Western capital. All of this makes engaging, or reengaging, with Fanon’s writing important and urgent today.

What makes Fanon’s work so uniquely powerful, though, is as much in how he wrote as it is in what he wrote. He wrote for the colonised, the occupied, the wretched. His prose is furious, poetic, sarcastic, and morally charged. He didn’t appeal to respectability and rejected the idea that the oppressed must ask politely for dignity. And in a world where settler-colonialism is not only alive but thriving – from Palestine to Kashmir – his words, forged in clarity and rage, still cut through the lies of empire with painful precision.

Perhaps this explains why Fanon’s impact hasn’t just been limited to politics and theory but has also rippled across cinema, literature, and radical art. His ideas helped shape Third Cinema and militant Black and Arab filmmaking, where form itself became a tool of resistance.

One of the best examples of Fanon’s influence on cinema is in Ousmane Sembène’s Black Girl (1966), which, echoing Black Skin, White Masks, tells the story of a Senegalese woman who migrates to France only to be stripped of her dignity and identity. The film captures precisely what Fanon described: how the colonised are taught to feel grateful for their own erasure. Med Hondo’s Soleil Ô (1970), Sarah Maldoror’s Sambizanga (1972), and even Gillo Pontecorvo’s enduring classic The Battle of Algiers (1966) are other notable examples.

Today, Fanon’s legacy lives on in the work of Palestinian filmmakers, diasporic artists, and revolutionary collectives across the Global South who reject victimhood and reclaim narrative power. “Colonial domination, because it is total and tends to make the colonised forget their past and to distort and destroy it, is fiercely opposed to national culture,” he wrote in The Wretched of the Earth. “Culture is the first expression of a nation, the first form of resistance.”

Crucially, Fanon understood that colonialism brutalises everyone it touches – not just the oppressed, but also those who enforce its violence. In the final chapter of The Wretched of the Earth, he turns his focus to the psychic toll of empire: the trauma carried by the colonised, and the moral injuries suffered by those who torture them.

Today, that insight rings true in unsettling ways. In the United States, military veterans have some of the highest suicide rates in the country. In Israel, more soldiers took their own lives in 2024 than in any year in the last decade. This shouldn’t create moral equivalencies. The plight of empire’s foot soldiers and the perpetrators of genocide warrants little sympathy when measured against the lives destroyed by their cruelty and barbarism. But it does expose a simple truth: no one enacts or enables systemic brutality and walks away whole.

This is why Fanon refused to see independence as symbolic. It was, for him, an act of collective self-recovery that was not just political, not just psychological, but necessary. “What matters is not to know the world but to change it,” he said.

A hundred years after his birth, Frantz Fanon still gives us the language to understand and confront the horrors of our unjust world, and the means to build something better. To truly honour him, we should do more than just remember his name. Because, as he wrote in The Wretched of the Earth: “Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”