Posted in

Music,

Posted in

Music,

How funk became the revolutionary soundtrack to ’70s Sudan

Text Sara Eldewak

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Sudan had one of the most innovative musical cultures in the region, and cities like Khartoum, Omdurman, and Port Sudan were alive with artists blending funk, folk, Afro-pop, soul, jazz and Eritrean influences. Sudanese funk wasn’t just a sound. It was a pulse running through the streets of Khartoum. Artists like The Scorpions & Saif Abu Bakr, Kamal Keila, Al Balabil and Sharhabil Ahmed transformed the dance floors into spaces of cultural rebellion. But one of Africa’s most vibrant times in music didn’t emerge in isolation, it grew out of the political and cultural shifts reshaping the country. After gaining independence in 1956, Sudan had entered a new era, and by the late 1960s and 1970s, Khartoum was transforming in ways that would shape revolutionary music forever.

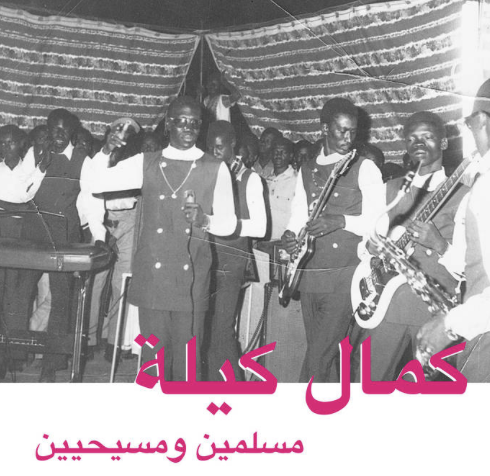

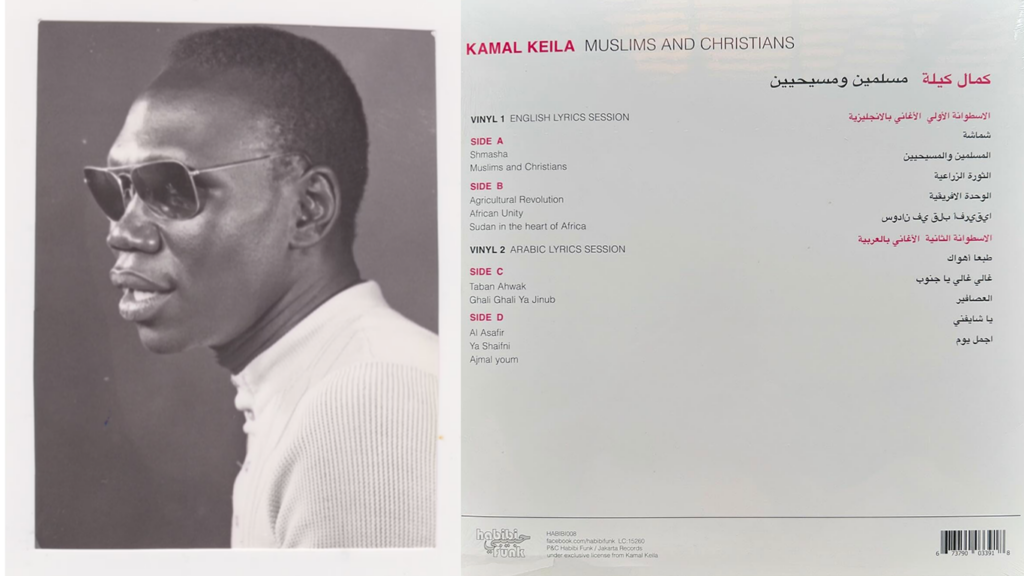

The youth were facing a range of circumstances, a large one being the impact of the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972). Hungry for modern sounds and experimentation, artists like Kamal Keila became key figures in Sudan’s jazz and funk scene. Kamal brought the conversations and artistry that the people craved, making his work a vital part of the musical culture in Sudan from the mid-1960s, up until the Islamist revolution in the late 1980s. His influences included James Brown, Congolese Rumba, Fela Kuti, traditional Sudanese music and many more. Kamal’s album ‘Muslims And Christians’ stands out as one of the most explicitly political records of the time. A record that was saved from erasure, tucked away in Kamal Keila’s basement, later restored in 2018 by Habibi Funk Records. Not only does the record confront sectarian tension, but it calls for unity across religion, class, and ethnicity in a period of rising division. Tracks on the record including “Agricultural Revolution” and “Sudan in the Heart of Africa” were uplifting and revolutionary through their profound lyricism, calling for change and reaffirming that the power has always been within the people. The record’s sharp commentary on corruption and inequality speaks volumes, and its message remains applicable in Sudan’s current political climate.

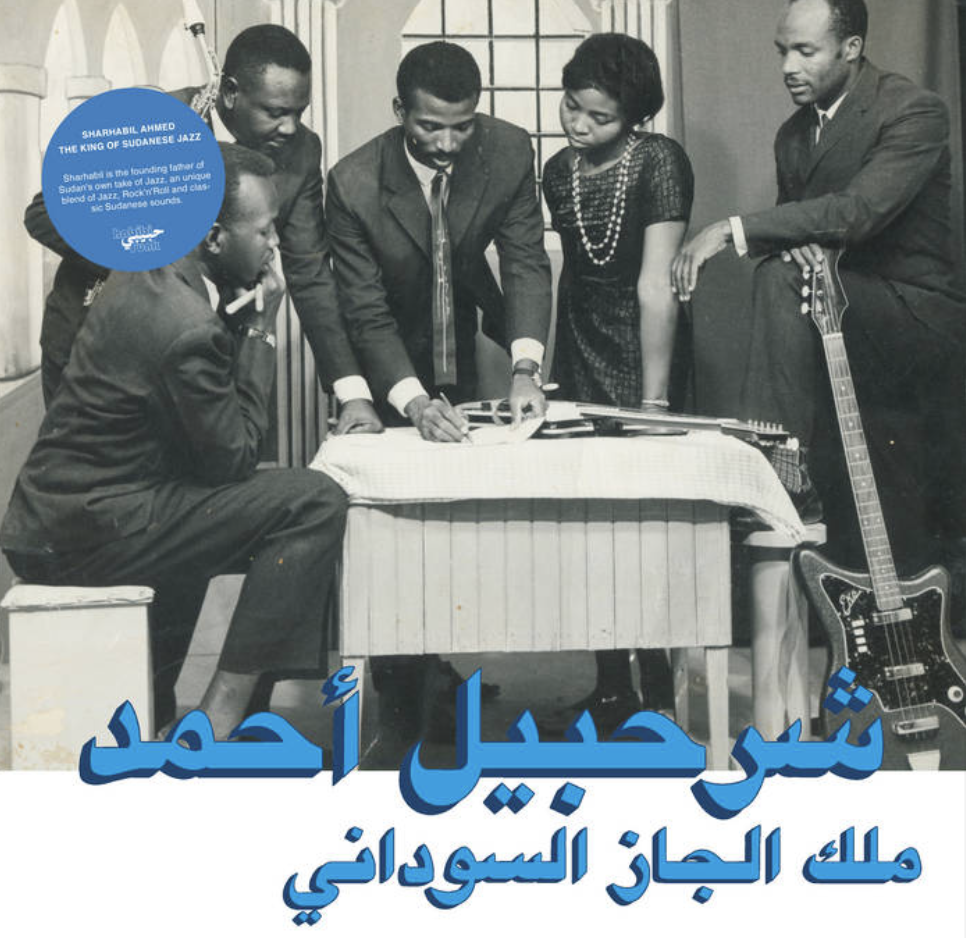

Another pivotal artist of this era was Sharhabil Ahmed, widely celebrated as “the King of Sudanese Jazz.” His unique sound occupied a foundational place in Sudan’s musical history, and his records remain some of the most important documents of the country’s funk and jazz fusion era. Known for his eclectic style of singing and composition, Sharhabil created a distinctive sound by incorporating newer styles of music, such as Western dance music, and older sounds like the traditional Oud, an instrument played in Africa for over a thousand years. Another key member of the group who played Oud was Zakia Abu Gassim Abu Bakr, who was the first female professional guitarist in Sudan. Tracks like “Zulum Aldunya” which translates to “The Cruelty of The World” not only generated social commentary, but challenged and addressed the hardships and frustration many Sudanese people felt, during a climate where public music was increasingly getting censored and creative expression was under pressure. Sharhabil’s body of work continues to be a space of expression and social critique.

As Sudanese artists continued to turn adversity into creativity, The Scorpions & Saif Abu Bakr were no exception. Led by Amir Nasser, also known as Amir Sax, the band combined unique sounds that fused Sudanese rhythms with funk, jazz, and Afro-pop. The band was formed in 1960 and was active until the 1980s. Their record “Jazz, Jazz, Jazz,” released in 1980 and reissued in 2018 by Habibi Funk, experimented with both playful and soulful instrumentals. According to an interview included with the reissue, the band faced a plethora of obstacles during the creation of the record. Many instruments were hard to come by in Khartoum, so they built their own drum kits and even borrowed a saxophone from a local high school. Despite these challenges, their music became a vital part of Sudan’s cultural landscape, proving that even instrumental tracks could carry revolutionary energy and speak to the resilience and creativity of a generation navigating turbulent times.

Following the 1989 coup that ousted Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi, mainstream music in Sudan increasingly became controlled, and lyrics were subjected to heavy censorship. Decades of authoritarian rule continued to stifle creative expression, and artists were forced to go into exile. In the midst of simmering political and social tensions, pressures that would eventually erupt into the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005), the once vibrant musical renaissance collided with an oppressive regime.

Today’s revival of Sudanese funk is about much more than simply nostalgia; it’s an act of reclamation. For many Sudanese and diasporic youth, resurrecting this sound is a reminder of the joy, rhythm, and unity that have always been tools of defiance, and a heritage nearly erased that still beats loudly beneath the surface, proving once again how music survives dictatorship and exile, and returns as a pulse of resistance. And ultimately, the body of work that came out of this era not only unites and honors the diverse ethnic groups of Sudan but is a testament to the strength and resilience of the Sudanese people.