Posted in

Music, Greentea peng

Posted in

Music, Greentea peng

The revolution will not be televised: A conversation with Greentea Peng on music, the politics of the self, and Palestine

Text Selma Nouri

After my conversation with London-born musician, Greentea Peng, I began to question the true meaning of the word ambition. In the New Oxford American Dictionary, it is defined as a “strong desire to do or to achieve something, typically requiring determination or hard work.”

Note how the definition makes no reference to the self. It is not defined as a “strong desire” to achieve professional success or material wealth. There is no mention of fame or fortune, only an essential spirit – a desire to achieve something.

As with many other things today, it seems that we have stripped the word ambition of its humanity. We have transformed it into a selfish endeavour, one driven by capitalist notions of what it means to be great. There is a justified greed involved in its spirit as a noun.

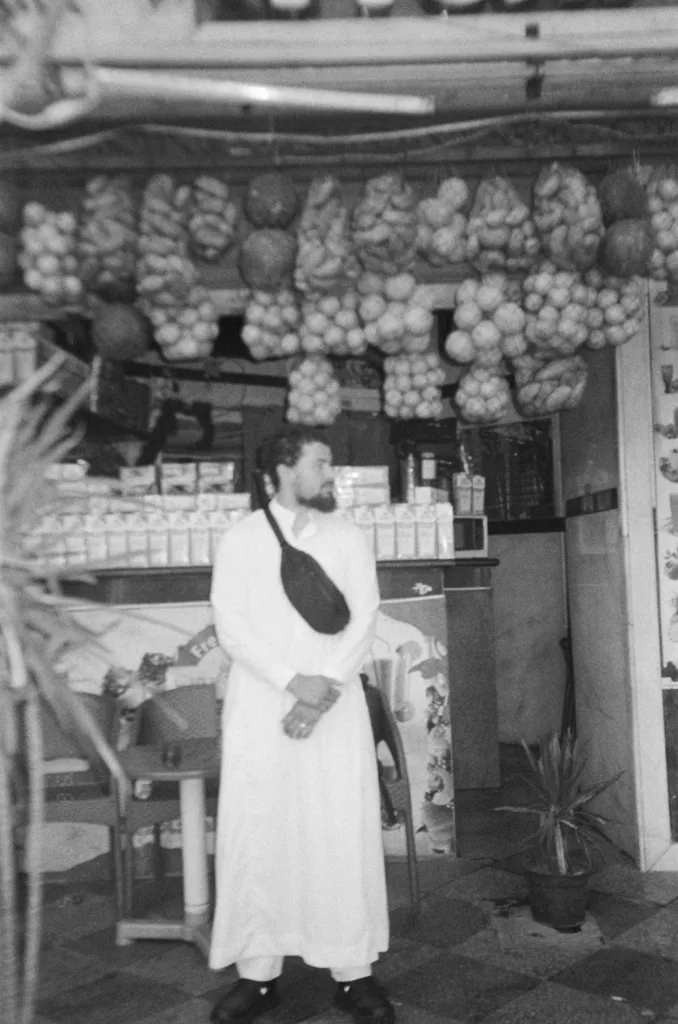

So when Greentea Peng, otherwise known as Aria Wells, said outright, “I don’t consider myself an ambitious person,” I didn’t think twice. The musician, whose roots span Iraq, Trinidad, Nigeria, and beyond, is anything but self-seeking. Her presence is grounded and reflective. The introspective nature of her soulful, psychedelic sound extends far beyond her music. It carries into her daily life, in the cadence of her voice and in the quiet depth of her thoughts. Wells may not be driven by contemporary visions of success or the material rewards of a career, but it’s clear that she is deeply conscious of her role in this world, not just as an artist but as a human being.

Therefore, as I later began to transcribe our conversation and reflect on the meaning of the word ambition, I realised that we both may have misunderstood it. She is ambitious but not for personal gain or recognition. Her ambition lies in something far more profound: in her faith in humanity and her commitment to truth. As a vocal advocate for the Palestinian cause, she displays far more courage – and yes, more ambition – than the millions who choose silence.

Throughout her life, Wells recounts having traversed both darkness and light. She has known happiness and hardship, escape and reckoning. Yet, through all of it, her empathy has endured. Her ability to turn inward and examine herself with honesty, I believe, is the true source of her strength.

A moment that stood out during our conversation was when she quoted the lyrics of American poet and singer, Gill Scott-Heron. “The revolution will not be televised,” she said. “It must take place within oneself first.”

Self-reflection, I believe, is the most ambitious endeavour one can undertake. It may not be publicly celebrated or rewarded, but its impact runs deep. In a world that is consumed by constant motion and the chase for material success, her willingness to slow down, turn inward, and prioritise inner growth is quietly radical and immensely profound.

Released this past March, Tell Dem It’s Sunny, her second studio album, serves as a sonic manifestation of this very practice. Drawing on an extraordinary depth of lyricism and personal storytelling, Wells commits fully to what she describes as “the self-political.”

At first glance, such an endeavour may appear immensely personal – or even apolitical to some – but in truth, it is the entry point for all politics. To meaningfully engage with the world, let alone imagine revolution, one must first be ambitious enough to confront the self – to reflect critically, unlearn inherited narratives, and cultivate an openness to change.

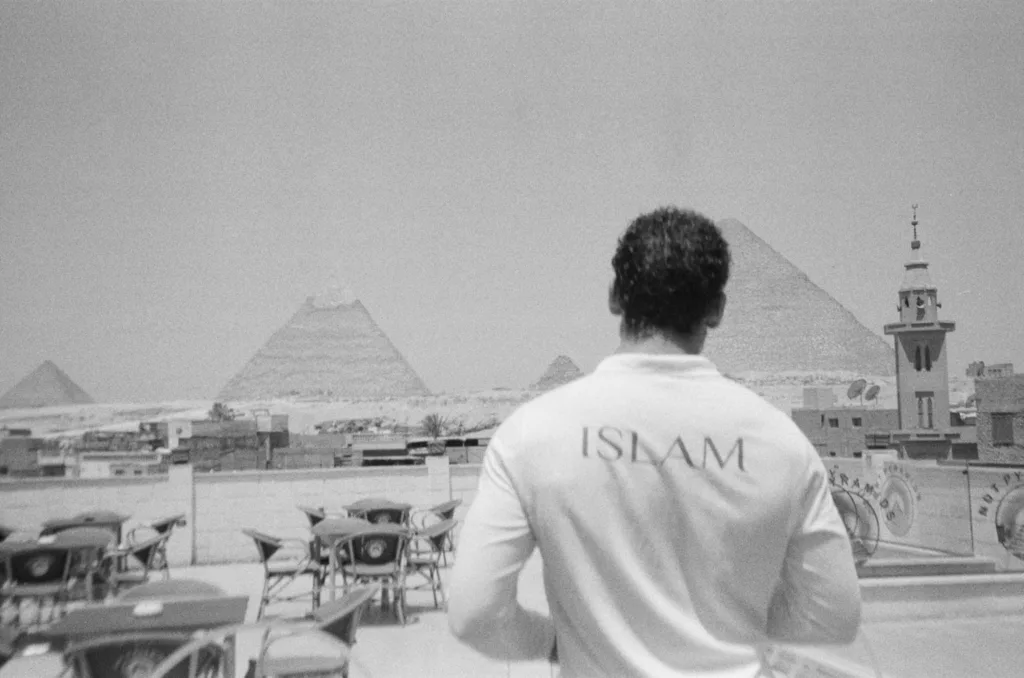

Having recently travelled to Egypt to join the march to the Rafah border crossing, Wells, who once wrestled with feelings of hopelessness and nihilism, has already overcome unimaginable internal terrain. Faltering moments at Glastonbury or unfinished missions are not failures; they are simply chapters in a much larger journey. As she explained herself, she may not have made it to the Rafah crossing this time, but she would do it again “in a heartbeat.”

Self-reflection, as embodied by Wells, is, I believe, the root of all empathy. And empathy, in turn, is the quiet engine for revolution. As history has reminded us, “the revolution will not be televised;” it requires active participation. The work must begin from within. Wells’ ambition lies precisely in this endeavour. It lies in her humanity.

SELMA: What first sparked your interest in politics? Do you feel that your multicultural background may have influenced or shaped that interest in any way?

GREENTEA PENG: I view politics as the interface through which we experience society. If you care about people or if you care about the direction in which our society is heading, then you can’t help but care about politics, because it is what shapes that very trajectory…Whether or not I agree with the system itself or how it is structured is a different question. For now, it is the way our society works. It remains the framework through which we experience our direct social reality, so we really don’t have the luxury of ignoring it.

Honestly, for me, I think it mostly comes down to an innate sense of care and sensitivity – a deep, often overwhelming awareness of my surroundings and my environment. This sensitivity has shaped my entire life, and it is something that I have always really struggled with. In many ways, I have never really had the choice not to care about politics. Even when I was young, I was always acutely aware of injustice. I remember in primary school, I used to run little market stalls for Amnesty International. They taught me about political prisoners, and I would write letters advocating for their release. So the interest has always been there…I can’t pinpoint the exact moment it all began, but I do remember when my disillusionment with society truly set in, and that was during the Iraq war.

I was very young when I attended some of the largest protests in London, marching against the invasion and sending a clear message to Tony Blair and the Labour government that we did not want to go to war. I remember watching the destruction on TV, fully aware of my Iraqi heritage. I have never met that side of my family, but knowing that some of my ancestors, or perhaps even living relatives, were still there made it all the more difficult.

That was when the depth of my disillusionment with society really evolved. From that point on, I think…Well, let’s just say, I have been very cynical from a young age. Yes, let’s put it that way. I have always been very cynical of the powers that be and the systems that claim to represent us.

SELMA: Absolutely, I can completely relate. I brought up the connection between your mixed background and politics because it’s something that I have reflected on a lot in my own life…I grew up in the US, but my mom is Tunisian and my dad is Afghan. Although our backgrounds are very different, I’ve found that being connected to multiple cultures has certainly shaped my sensitivity to social and global issues…It has granted me a far more layered and nuanced understanding of the world, one based on empathy and human understanding as opposed to technical politics.

Much like you, I think being of a mixed background also sparked a deep sense of disillusionment. From an early age, it became clear to me that the reality of conflict and displacement was far more complex than what I saw on mainstream television or learned in school. So I am always curious to hear if others with similarly mixed or diasporic backgrounds feel the same – whether that sense of cultural in-betweenness has also driven their political consciousness in some way.

GREENTEA PENG: I really believe that it affects one’s ability to have a malleable mind. When you are of a mixed identity, you have no choice but to be open-minded, and I think that opens up a lot of opportunities for political thought and reflection. You are encouraged to question and consider alternative opinions, to seek new ways of thought. For many people, it is the starting point – the entry into a deeper political consciousness…I am sure that a lot of my own thoughts and interests are rooted in this impulse or this instinct of open-mindedness.

SELMA: I’m curious to know where music fits into all of this. When did it first become part of your life? Do you view music primarily as a form of self-expression, or is your passion fueled more by your sensitivity and desire to connect with others?

GREENTEA PENG: It is definitely a balance. Music has always been a constant in my life. My dad is quite musical, and growing up, there was always something playing in the house. But the kind of music that initially pulled me in, or the kind I’m most drawn to, is revolutionary music. For instance, I grew up listening to artists like Miss Dynamite. Her work might not tackle global politics, but she speaks very powerfully about issues in her local community – and there is something deeply revolutionary in that…Music of that kind, rooted in everyday life and community experience, is still political. It’s consciously engaging with themes that affect people on both an individual and collective level.

I mean, all of my work is essentially a form of self-expression, but I believe we’re all intrinsically connected. So even when I’m just expressing myself, I’m also expressing this small part of the collective space we all share, you know? That said, I never sit down to write a song thinking, “I want this to be about a certain political topic or I want this to reach a certain number of people.” It’s not like that. But I do believe that creativity, in general, is about tapping into that shared space – a space we can all enter and connect through. Creativity is, at its core, a communal experience.

SELMA: When did you know that music was something you wanted to pursue professionally?

GREENTEA PENG: I have never been an ambitious person. I dropped out of school at the age of fourteen and have been working ever since. I have always enjoyed not being tied to ambition or the pressure of wanting to achieve anything other than peace.

For me, singing was never a means to an end. I had never really planned to make a career out of it. I just sang because I enjoyed it…The rest came together quite naturally. I had a band and was singing in my spare time, living abroad, and just enjoying my life. When opportunities came along, I took them, and they happened to lead me here. None of this was ever planned.

SELMA: In a previous interview, you described yourself as both colourful and dark. Could you elaborate on that? Which side plays a more significant role in your music-making?

GREENTEA PENG: I suppose what I meant is that I tend to traverse the extremes. As much as I can light up a room and bring warmth into it, I can just as easily stir a hurricane. If I’m honest, it’s often the darker side of me that informs my creativity, the one that carries the weight or the desperation. Those are the feelings that push me into the studio or pull me toward the pen and paper. As I’ve said, I’m very sensitive to my environment – and right now, it is quite a negative time, isn’t it?

SELMA: Of course.

GREENTEA PENG: I think it all comes down to embracing the totality of the human experience, which, of course, traverses both dark and light. Inevitably, you can’t have one without the other.

SELMA: When you were working on your most recent album, Tell Dem It’s Sunny, what did that creative process look like for you? I came across an interview where you referred to it as a “self-political” album, which really stood out to me – especially given how politically charged the world feels right now. So, I am curious to know, what led you to take a more introspective approach with this project?

GREENTEA PENG: I think it just reflects where I was at the time. When I began making the album, I was going through a lot of personal change. It was a really intense, transitional period in my life, and that’s what came through in the music. At one point, I even thought, “Wow, this feels selfish to put out right now.” It felt really self-centred in a way. However, I have never been one to pretend, and that’s just where I was at the time. I wasn’t going to force anything else. That’s not to say I’m not working on more political material in the background, but with this project, the themes I needed to process and what came together naturally led me somewhere more introspective.

SELMA: Of course. I have read that some artists find it difficult to follow the news because being in a “constant state of worry” can interfere with their creativity. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. How does your own creative process either support or challenge that view?

GREENTEA PENG: I guess to each their own. What inspires one person might cripple another creatively. For me, I’ve chosen not to watch the news. Since I was about 15, I began to withdraw myself from that world because it felt like nothing but propaganda. I do tune in occasionally, just to understand the narratives being pushed. I find that interesting, but I have learned not to trust, essentially, anything that Babylon is telling me through the TV. That’s why I mostly avoid the news.

It’s complicated, and I really struggle to find a balance. On one hand, I ask myself, how dare I enjoy the privilege of peace? How dare I not worry when so many are suffering? But on the other hand, we’re constantly bombarded with information, and that can’t be natural for the human mind. We can’t be exposed to an endless, overwhelming stream of news and content, 24/7. And let’s be honest, the algorithm relentlessly pushes the negative, the worst events happening across the world. This is a completely new phenomenon, and I don’t think our brains are equipped to process it all. I struggle with it myself. There are times when I sink into deep bouts of depression and have to step away from Instagram for a while.

So, I really do understand both sides. It’s about balance. I do think some people take “protecting their peace” too far – what I’d call a kind of ignorance. You know, the ones who smile and wave in the face of oppression. As long as they’re not directly affected, they don’t want to know about the suffering going on in the world – or worse, they just don’t care. For me, that’s something entirely different. What I believe is that we all need to give our nervous systems a bit of rest. What is happening right now is incredibly intense, so it becomes a constant balancing act of not burying your head in the sand while also not torturing yourself with endless exposure. That kind of emotional burnout ends up being counterproductive. It can actually hurt the cause…I’ve been there. I have fallen into deep ruts where I feel completely hopeless and helpless. And if you’re not careful, that can quickly slip into a form of nihilism.

SELMA: If not the news, what sources do you turn to for information?

GREENTEA PENG: I mostly connect with people on the ground or gather insight through travelling. I’ll tune into the news here and there, but when I do, it’s usually Al Jazeera – not the BBC or mainstream outlets. I am constantly on the lookout for new, alternative sources. But more than anything, it’s the firsthand stories and perspectives that I value most.

SELMA: With regard to Palestine, when did you first become engaged with the issue or begin to feel strongly about it? I imagine for you, it began well before October 7th.

GREENTEA PENG: Yeah, of course. I think I went to my first rally for Palestinian rights when I was around 15 or 16. I actually learned about it through an older Iranian friend. He was the one who really opened my eyes to the issue and took me to that first rally. So, Palestine has been on my mind for years now.

Obviously, it’s one of those topics that’s left out of standard education. In school, we’re taught a version of history that aligns with and reinforces the Western narrative – a version that keeps the show running, so to speak. The only event we studied in depth was the Holocaust…There was no mention of Palestine, no discussion of the ongoing genocides or apartheid systems shaping the present day. Those realities were omitted entirely.

SELMA: I read that you recently travelled to Egypt to join the march to the Rafah border crossing. If you’re comfortable sharing, I’d really love to hear more about what that experience was like. What inspired you to take part? And even if things didn’t go exactly as planned, what did you take away from it?

GREENTEA PENG: Yeah, it was definitely an interesting experience. I wouldn’t say it was a tough decision, because from the moment I heard about the march, I knew I had to join. Of course, I have a two-year-old, and I’m already away from her a lot due to work, so in that sense, it was a big decision – but it wasn’t a difficult one. Leaving her, especially with all the uncertainty surrounding the situation, weighed heavily on me. I’d never been to Egypt before, and there were so many unknowns. However, anytime I began to dwell on my own fears or doubts, I’d remind myself of what the people in Palestine are going through every single day. They don’t have the luxury of choice.

So my younger brother and I decided to go. We committed to the trip, to the mission. Unfortunately, by the time we arrived, the initial group had already marched, and we missed the last procession. The authorities had already shut everything down. So the second wave of people that were meant to cross had pulled back. It was essentially over by the time we got there.

Even if the outcome wasn’t what I had hoped, the act of going was never optional. It was something I had to do. I mean, there is blood on all of our hands, and I carry a lot of guilt and shame knowing that my taxes contribute to what’s happening right now. And honestly, every day I feel like a hypocrite. My music is on Spotify. It’s getting played on BBC Radio. It’s hard. There is this internal conflict that never seems to go away. So for me, the question was never “should I go?” – it was more like, “how can I not?”

Sure, I’m sending money, raising awareness, doing what I can from here, but it never feels like enough. So when the opportunity presented itself for me to be there physically, to stand in solidarity, I knew I had to go. Even though it was clear that the authorities would have never let us make it to the crossing, it still mattered as a symbolic act, a sign of solidarity. Because at the very least, our brothers and sisters over there need to know: we see you. We’re with you. We don’t support what our governments are doing. They don’t represent us….So yeah, it had to be done.

There was fear, definitely a lot of adrenaline too, but it was a big decision with no real alternative. And in the end, from a practical point of view, it felt like a failed mission. We didn’t get through. A lot of people were arrested. Others managed to make their presence felt, but personally, I left feeling kind of useless…Although while I was on the ground in Cairo, I was introduced to an incredible NGO providing education and support for members of the displaced Sudanese community. Because of course, on top of what’s happening in Palestine, there are ongoing conflicts in Sudan, Congo, and elsewhere. The world is full of inhumanity right now, genocides and atrocities that are constantly being overlooked or ignored.

Intention, of course, matters, and even if the mission didn’t go as planned, I would do it again in a heartbeat. I just wish more people had shown up. Anyone who has the means should seriously consider it, because if the last two years have shown us anything, it’s that we can’t rely on anyone – not the UN, not international courts, not so-called human rights institutions. It’s all a façade.

The only real path to change is through direct action. People must be willing to take to the streets, willing to make sacrifices. That is what it is going to take – a complete break from comfort and convenience. The truth is, we are all benefiting from the empire in some way. There’s no denying it. We are all complicit, whether we like it or not. So we must be willing to prove that we are no longer going to accept complicity. We must be willing to prove that we are okay with discomfort and inconvenience for the sake of humanity. As I said, any meaningful change is going to come from the people, not institutions. That’s why, despite everything, it felt exciting to be there. It felt like I was part of something. Because honestly, from a young age, I’ve always felt ready. Like, if there’s going to be an uprising, I want to be there. I want to be part of it.

And for a moment, it really felt like okay, shit, maybe this is the start of something real.

SELMA: I would like to delve deeper into the notion of symbolism. Do you think artists and public figures have a responsibility to engage with politics, especially when it comes to something as urgent and ongoing as Palestine? There seem to be lots of opposing views on this. Some argue it is not their place, while others view it as a deeply symbolic and necessary contribution within the broader movement. Where do you stand on that?

GREENTEA PENG: I think if it’s genuine and comes from an authentic place, then absolutely, share your truth. However, if that is not the case, then maybe it’s better to stay quiet. To each their own. I just know what feels natural to me. I know what stirs something in me, what makes my blood boil. For me, speaking out is intuitive. It is not a choice. But if that urgent sense of humanity doesn’t come naturally to someone else, then it doesn’t.

Then again, I do find it really jarring when people comment on my work and say things like, “stick to music,” or “keep politics out of it.” That mindset is difficult for me to understand…I find it really jarring. Art is political. How could it not be? Art is the medium through which we express our emotions, beliefs, ideals, and lived experiences. And politics – aside from spirituality – is the most immediate way that we engage with the social world around us, the realities that shape who we are. There is a direct line between politics and our emotional experiences, which is why separating politics from art feels unnatural to me. They’re deeply intertwined, or at least, that’s how I see it.

SELMA: You mentioned spirituality. I am curious to know, what does faith mean to you?

GREENTEA PENG: Faith has definitely been a kind of dance throughout my life. It’s always been a “you move, I move” kind of relationship. I’d say I have a strong foundation. I’ve always believed in God or a creator – something higher and more powerful than us.

However, navigating faith, especially with my mixed heritage, has been complex. It’s been an ongoing process of figuring out where I fit within the religious landscape, and to be completely honest, I can’t say that I have fully found my path yet.

If there is one thing I know for sure, it’s that I’ve been deeply moved by what we’ve witnessed in Palestine over these past two years. The people have shown an unwavering faith and resilience – a kind of steadfastness that I don’t think a Western mind could even begin to comprehend.

I have a friend in Gaza whom I speak to almost every day, and I’ve been supporting him over the past year. He’s an incredible poet, a true intellectual with such a beautiful way with words. Speaking to him, knowing what he’s living through, is often surreal…He’s living through what can only be described as the annihilation of his homeland – his family, his friends, his neighbours. And yet, there remains a grace and strength in him that is difficult to put into words. He still asks how I’m doing. He still finds time, amid unimaginable horror, to check in on me.

The courage and kindness that the people of Gaza continue to show, even in the face of such relentless violence, is beyond anything I’ve ever witnessed. It’s an abomination, truly. In our lifetime, the violence against the Palestinians is the most horrific we have ever seen, and still, they carry themselves with dignity. They still show up each day with unwavering faith, still praising Allah and holding on to their spiritual practice. That kind of strength…it’s humbling. I think it has shaken a lot of people in the West. It’s shown us something we’re not used to seeing, something deeply powerful and profoundly human.

As for the West, I believe we have been severed, completely cut off, from God and spirituality. So when we witness what is emerging from Palestine, it is far beyond anything many of us can fully comprehend. Even their attachment to the land is moving. I don’t know if it resonates so deeply with me because I’m mixed race and have never truly felt a sense of belonging anywhere, or if it’s simply because I can feel the depth of their humanity, the love they carry for their traditions and faith. It all runs so deep. Their love is in the soil. It’s in the roots of the olive trees. It seeps from the blossoms. It’s beautiful, but it’s…it’s heartbreaking. It makes me emotional.

What we are witnessing, I believe, is a direct assault on the human spirit. Despite everything, the Palestinian people remain tethered to God by a sacred thread – a living, unshakable faith. It is this bond that is under siege…The attacks against the Palestinians are an attempt to sever that last, sacred connection between a community and their faith. It is an erasure of the last truly God-fearing, merciful people.

Yet, no matter how ruthless the attempts to sever that connection, the Palestinians have proven that it endures. They have shown us that when faith is real, when it is lived and embodied, there are things that can never be broken.

SELMA: How did you connect with your friend in Palestine?

GREENTEA PENG: It began quite simply. I came across a fundraiser of his and donated some money. We stayed in touch and began sharing writing back and forth. It became my one tangible way of making a direct impact and actually supporting someone on the ground…There’s a direct line between us, and I’ve made it a priority to nurture that connection and keep it strong.

But it’s heartbreaking. Every morning, I wake up and wonder, “Will he message back today?” I’m constantly bracing myself for the day he doesn’t, and that feeling, it’s completely alien to my Western fragility. I have never known anything but safety and convenience. I have never had to live with that kind of uncertainty. I have never had to question whether someone I care about might be alive, dead, or injured.

Their resilience in the face of all that is beyond anything I’ve ever known. It’s moving.

SELMA: I read that you became a mother recently. I’m curious, how has that experience shifted your perspective, if at all? Has it changed the way you see the world, your approach to music, or even the way you engage with what’s happening politically, especially in places like Palestine?

GREENTEA PENG: I think before becoming a mother, it was easier for me to slip into a state of, dare I say, apathy or nihilism. I’d often find myself thinking, “What’s the point? Everything’s already broken. Nothing I do will make a difference.” But now that I have a child, I’m forced to have hope.

Bringing a child into this world without hope would have been an incredibly selfish act. So now, I can’t descend into the same dark places I once did. I can’t traverse the same depths. I have to believe there’s a way forward, a possible future worth fighting for because the alternative would be accepting that my child is doomed – and that’s just not an option.

Honestly, becoming a mother is probably the best thing that’s ever happened to me. It’s incredibly challenging, but I can feel it shaping me into the woman I’m meant to be. It’s mad. It’s a trip, but it’s powerful.

SELMA: Speaking of hope, you recently posted about performing. You mentioned it was beginning to feel futile or even superficial. I’d love to hear more about that. What is it about performing, specifically, that ignites those feelings in you?

GREENTEA PENG: I still stand by that comment. Performing does feel somewhat vacuous to me. I’ve always considered myself an authentic performer. I am very much myself on stage, so what you see is what you get. That is why I have never considered myself a “performer” in the traditional sense. I don’t put on a persona or a polished version of myself. It’s just me.

But lately, I’ve felt like I have to step into a role just to get up there and sing, and that’s been really difficult. Given how sensitive and harrowing things are in the world right now, stepping on stage and pretending everything’s okay feels deeply inauthentic. It feels like we are all pretending everything is normal when in reality, I just want to scream or break down in tears.

So yeah, these last few months have been really challenging for me in that regard. Of course, there is another side to it, too. Music, especially live music, has the power to bring people joy, to lift spirits, to raise the vibration, and I do believe in that…Again, as with everything in life, I am just trying to find that balance. I am constantly learning how to show up honestly while still holding space for what I love and performing my music. I believe it’s about navigating both truths at once.

SELMA: How did performing at Glastonbury this year play into those feelings? What was it like performing at a festival that has such a strong history of political activism and expression?

GREENTEA PENG: To be honest, I struggled with Glastonbury this year. Initially, I didn’t even want to go. I had been watching the news every day for two weeks straight. I was absolutely consumed by it, so the act of performing there just felt out of touch and inappropriate.

Eventually, as time passed, I decided to just go, and once I got there, I thought, “you know what, I’m here now. I’m going to try and enjoy it, to make the most of the moment.” I had written a really long piece to read on stage, and I put a lot of pressure on myself…I felt like I had to say or do something big. But when the moment came along, it just didn’t feel natural. I said a few words, but reading the whole thing felt forced, so I decided not to. I had been at the festival since Wednesday. I was a bit tipsy, and it just didn’t feel right. When it comes to something so important to me, I want anything I say to be meaningful and grounded in respect. And in that moment, it just didn’t feel like the right time. I wasn’t going to force something that didn’t feel authentic or appropriate.

Of course, afterwards, I beat myself up a little bit. It was a televised performance, a huge platform, and I felt like maybe I’d wasted the opportunity to say something meaningful. But at the same time, it wouldn’t have been right for me in that moment, and that has to count for something too.

SELMA: I honestly find that really beautiful – your unwillingness to move against what you genuinely feel. There’s something powerful in how you stay so true to yourself, and it really comes through. As we discussed earlier, you described your latest album as “self-political.” Can you define that for me?

GREENTEA PENG: It’s really about being on the path toward self-knowledge. It’s the missteps of the mind – the fluctuations in mental states, the internal debates, the chaos, the inner tyrant. All of that. It’s about navigating the relationship between the microcosms and the macrocosms….Before we can turn out, we must turn inward. We have to address the turmoil within. You know what I mean?

The revolution won’t be televised. It must take place within oneself first.

SELMA: So now, as you have set on this path toward self-knowledge, what do you hope for the future? What are your plans?

GREENTEA PENG: Of course, I’m writing music, but really my hope for the future is that people, especially in the West, wake up and recognise the role we play in sustaining this materialistic bubble we live in. We need to recognise the real costs of our comfort, the price paid by the Palestinians, the children in Congo, the people of Sudan….My hope is that we come together and rise up against the powers that be – those who rely on exploitation, oppression, and the suffering of others, not just for survival, but for their excess and luxuries.

I truly believe we have the potential to shape a better world. There’s so much untapped strength and potential within the human race, and I have faith that we can rise to meet it. I think that’s exactly why the attacks on our collective movement feel so concentrated. They’re coming at us from every direction: the media, the education system, healthcare – everything. We’re being bombarded on all fronts because they know how powerful we are when we’re united. That, I believe, is their greatest fear: collective consciousness and collective action. No matter the cost to our comfort, we must stand firm against their attempts to silence and suppress us…The time has come to dismantle these unjust systems and rebuild something human.

SELMA: That actually leads me to one final question. Do you have any advice for young creatives, or young people in general, who might be struggling with a similar inner turmoil in navigating the intersections between art and politics, especially in a moment like this? I know you’re still on that journey yourself, but is there anything you’d like to share with those who might be feeling lost, overwhelmed, or unsure of their place in it all?

GREENTEA PENG: Just pour everything into your art. Try not to let it consume you. Channel your emotions into the creative process and allow that to take over. It’s a metamorphosis. You are transforming feelings of desperation, sadness, anger, and rage into something more beautiful, or at least something meaningful. All of those emotions are valid and have their place, but if they consume you, it becomes counterproductive.

That’s exactly what those in power want: to keep us hopeless, vibrating down low, and feeding into the existing dread. So don’t let that happen. Pour your feelings into your art in whatever way feels right. It doesn’t need to be pretty or palatable. Some of our feelings are ugly – allow them to be so. Allow your art to reflect the truth.