Posted in

Life & Culture,

Posted in

Life & Culture,

How do you archive a revolution?

Text Omnia Saed

What matters most to you at the end of the world? That’s the question Reem Aljeally and I wrestle with as we discuss her role as curator, artist, and founder of The Muse—one of the few institutions championing Sudanese art and culture since the war began.

Since April 2023, Sudan has been engulfed in conflict. Numbers only begin to hint at the scale of the devastation. The Economist reports that at least 150,000 lives have been lost, though counts are hard to track and believed to be widely underreported, with makeshift cemeteries so vast they’re visible from space. Over 10 million people—about a fifth of Sudan’s population—have been displaced, including Reem, who now lives in Cairo.

It’s a catastrophic end for a nation that, just a few years ago, was transformed by a civilian-led revolution. That’s the aim of war: it causes brutal harm to its people, but it also works to erase all evidence of a nation’s past, its cultural memory.

Khartoum’s National History Museum has been looted, critical seed banks destroyed, animal sanctuaries pillaged, and Sudan’s rich artistic and linguistic traditions silenced. Kamala Ishag, one of the country’s most prolific painters, confirmed that her home—once a repository for much of her work—was completely burned down.

Founded in 2019, The Muse emerged during both a pandemic and a revolution—just three years before war erupted. “The Muse was born into turbulent times since 2019, and it continues to exist amidst turbulence,” Aljeally notes. At its inception, Sudan was experiencing a cultural renaissance. Murals defying oppression appeared on city walls, galleries emerged overnight, and artists, musicians, and poets expressed their hopes for a transformed world. In 2022, The Muse Multi Studios joined this movement, opening its first space in Khartoum with the “Muse Gallery.” The venue quickly established itself as one of Sudan’s leading art spaces by hosting group exhibitions, offering residencies for emerging talent, and launching Bait Alnisa—a platform dedicated to Sudanese women artists.

When the war broke out, people fled immediately, unable to grab or think critically about what to take with them. Entire art collections and photo albums, mementos, and heirlooms were lost–an entire archive of Sudanese cultural history erased instantly.

“Reem was one of the first curators managing exhibitions in Sudan,” explains Marwan Mohamed Hamza, the group’s program manager. “We had a space, trees, artwork, cameras, equipment—whatever we had at our disposal. Until suddenly, one day, we had nothing.”

It all vanished—left behind or lost.

“I don’t think people fully understand how heavy this moment is for our community,” says Hamza. “If I had children, what would they see? Nothing.”

It’s taxing work, entirely unpaid, and amidst people’s struggle for survival, often seen as menial. People are depressed, sad, and alone. “We still exist and we’re still breathing, and that’s a miracle,” says Hamza. Their work continues out of deep commitment: someone’s got to do it.

“Who’s creating your work and who’s archiving it? Who will tell the story of why and how it was produced?” asks Rayan Alnayal, Sudanese artist, educator, and co-founder and director of the creative studio Space Black. “We should stay vigilant, and I know it’s tough for those in such vulnerable states, but now more than ever, our work must sustain us and remain in Sudanese hands.”

Fittingly, The Muse’s latest project is the Sudan Art Archive, a digital repository preserving artwork produced by Sudanese artists from 1975 to 2025. The team is reaching out individually to artists for digital copies of their work, annotations, and records—with the hope that the loss they’ve suffered at the war’s onset will never be repeated.

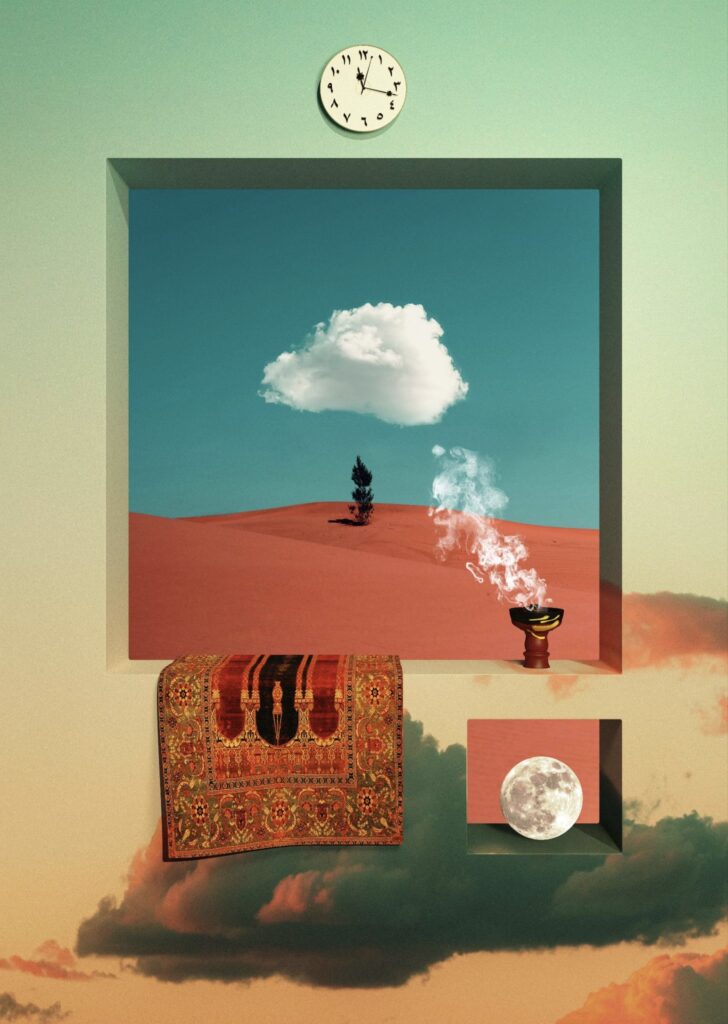

When you look at Reem’s art, you’re instantly mesmerized by a recurring image: a listless figure with large, downcast eyes drenched in hues of red, crimson, coral, and rose, lounging languidly in the scene. There’s an air of existential fatigue—as if the world’s trials have left it utterly spent.

“What are the things that matter most when we face the end of the world?” Aljeally asks, recalling the items she would have taken at the onset of the war. “I would have wanted to take memories—whatever they are, whatever they resemble. If a memory is a photo, or a small book, or something else, that is what I’d choose.”

“But what would I want to leave behind?” asks Reem. “I’m going to leave behind the work I do now.” She adds, “One day we’ll go back to Sudan and reopen our space.” Until then, there’s work to be done.