Posted in

Art & Photography, Dazed MENA issue 03

Posted in

Art & Photography, Dazed MENA issue 03

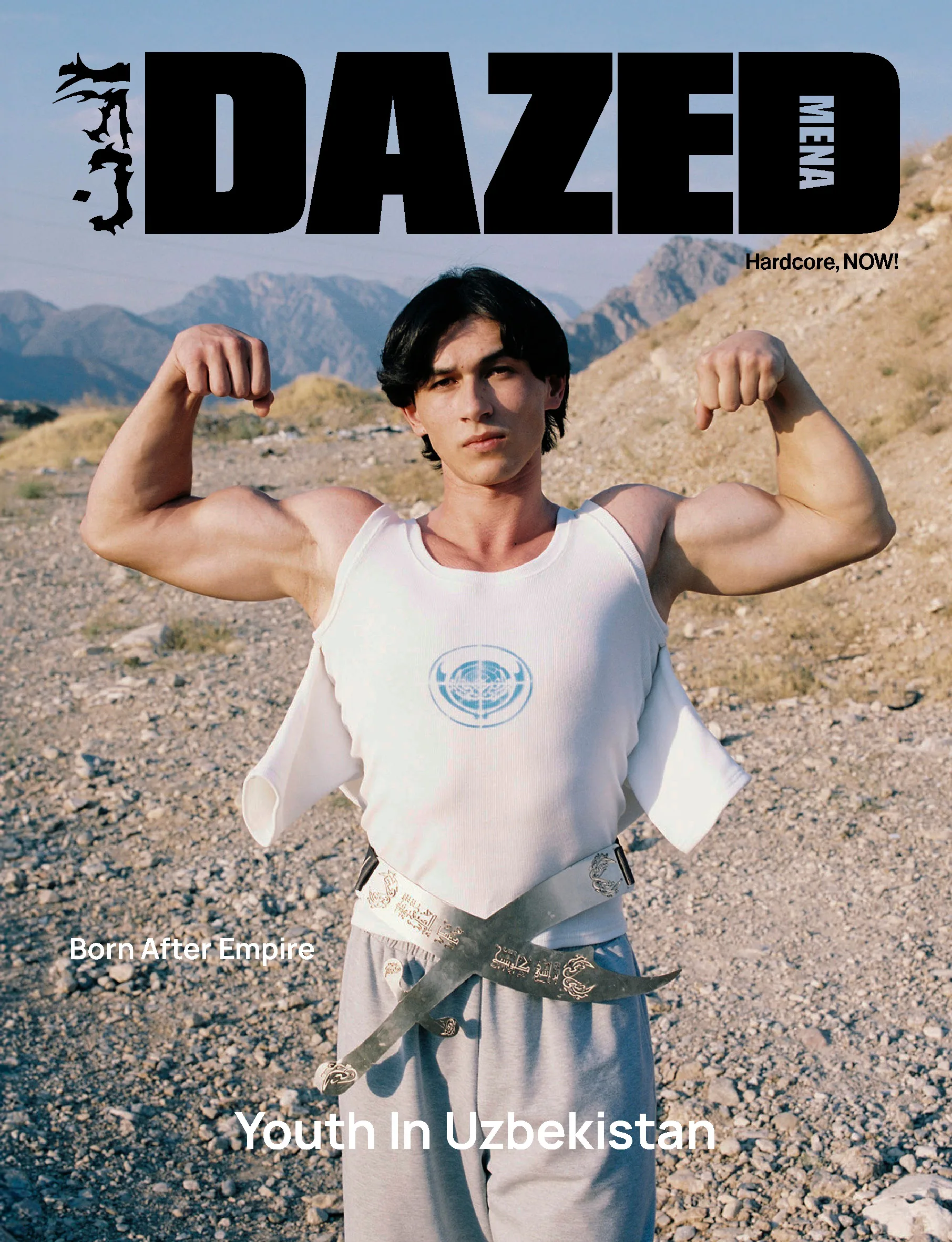

Born after empire

Text Zumrad Mirzalieva

Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia. Before the invention of modern borders and nation-states, this territory was divided into khanates ruled by emirs. In the 19th century, it was colonised by the Russian Empire during the Great Game with Britain, and later became part of the Soviet Union. Because of this history and its geographical location, the country is multi-ethnic. Islam is predominant, alongside Christianity and Buddhism, with a deeper layer of Zoroastrianism that predates the major religions.

We speak Uzbek, a Turkic language, but Uzbekistan is also home to both Farsi speakers as well as ethnic Tajiks and Iranians. We are sedentary, unlike our neighbours in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. And like several centuries ago, when Uzbekistan sat in the middle of the Silk Road, we are still bound by the same geopolitical constraints. The country stands right in the middle of large imperial states like Russia, Turkey, and China, whose soft power is visible in everything from city infrastructure and pop culture to education and economy. Uzbekistan is a country constantly reframed, reimagined, and fetishised. Its identity is forever under construction, its image traded between those who control it and those who resist it, neither producing a picture that feels fixed.

Weeding through the shrouds of Empire in an attempt for continuity, however arbitrary, our current state-led image creation attempts to arrange symbols into a seamless storyline, forcing structure on foundations that were never this neat. Grandiose reconstructions of old-town quarters are pushed to completion in time for visiting delegations, while revivals of traditional crafts are orchestrated with the ‘help’ of external experts (even when the dynasties who work in them never actually stopped). It conjures a strange vision: a future imagined backwards, shaped for audiences who won’t look past the façade where resources flow unevenly, infrastructure is still playing catch-up, and the independent culture scene holds together with whatever it can gather.

Within this landscape of staged grandeur and fragile alternatives, Hassan Kurbanbaev’s practice emerges. He came of age in the 2000s, when Uzbekistan was one of the most closed-off countries in the region—rigid state control, an absence of free speech, and borders that made it very difficult to enter or leave. These were the years that shaped his youth – years of constraint and introspection – and left behind a melancholy that still persists across generations, despite the radically different feel of Uzbekistan today.

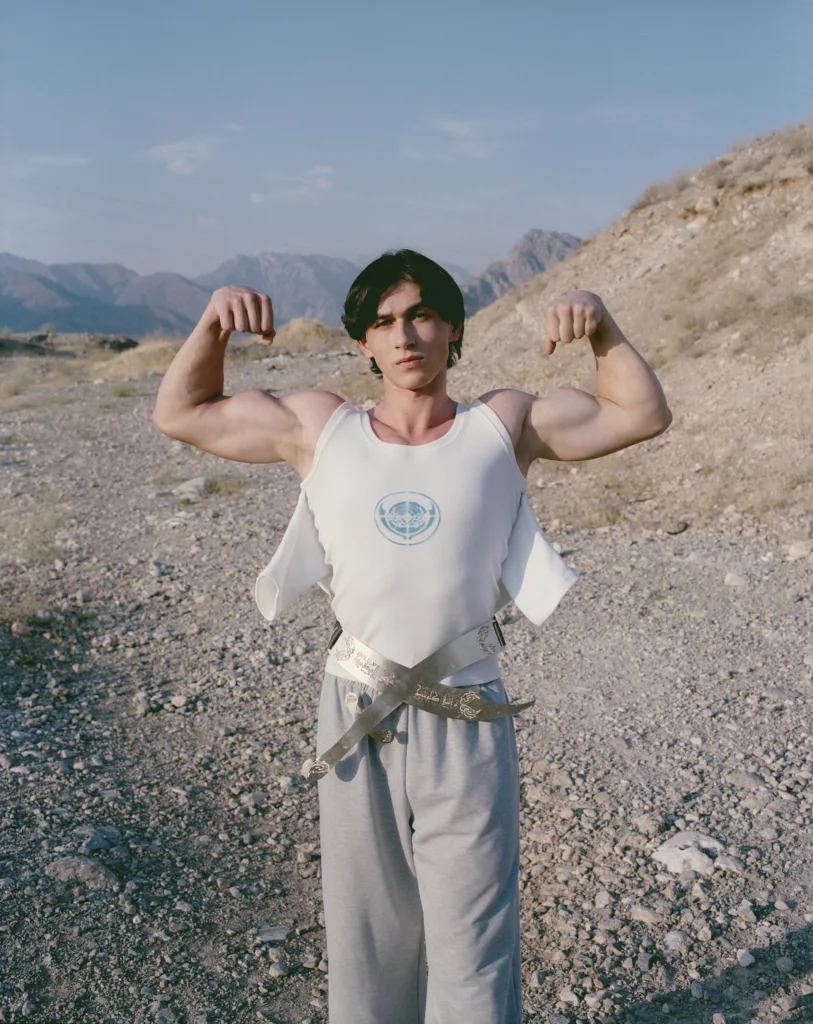

Trained as a cinematographer at the Uzbekistan State Institute of Arts and Culture in Tashkent, Kurbanbaev quickly realised he didn’t fit within the rigid hierarchies of a film crew and turned to radio instead, curating his own programmes of electronic and house music. He returned to the image eventually—not the moving one but photography, as it allowed him to pause, to hold contradictions in a single frame. “I think I’m always searching for a thread between myself and what I want to show,” he explains. “Youth is that part of life where you feel everything – emotions, anxieties, dreams – very deeply. Those are the strongest feelings, and you carry them all your life.”

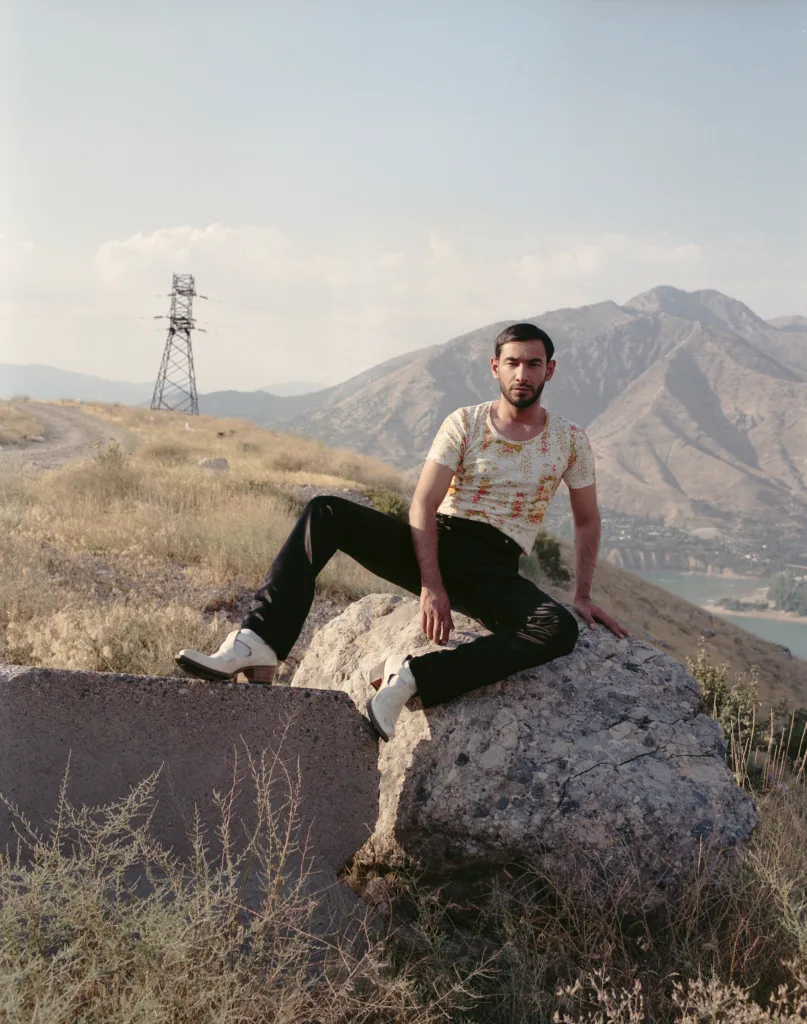

His photographs are often infused with that intensity and melancholia, coloured by the aftertaste of sunsets and youthful reflection. In his well-published series Logomania (2019-present), this sensibility takes on Uzbekistan’s contradictory desire for lavishness: young people in modest domestic settings draped in the luxury logos of western brands. As tradition and consumer culture fold uneasily into one another, Logomania makes visible a kind of ceremonial beauty that is both sincere and ironic, a performance of abundance inside conditions where abundance remains fragile. It is neither parody nor endorsement, but a mirror held up to Uzbekistan’s own image politics, where state-led extravagance and international aspiration coexist with delicate infrastructures and unresolved histories.

Much of his work, particularly for Logomania, is a negotiation with the nostalgia that saturates Uzbekistan’s culture, not as a straightforward narrative, but an ambivalent force. A craving for the vestiges of power, it occasionally clings to Soviet aesthetics, repurposing propaganda slogans, staging 80s-themed parties, or turning scarcity into a style. At other times, it drapes itself in images of state grandeur, polishing tradition into a spectacle of continuity and stability. Both gestures flatten history, one by recycling its visual debris, the other by airbrushing it into permanence. As the late Russian-American cultural theorist Svetlana Boym reminded us, nostalgia can be reflective or restorative. Here, it flickers uneasily between the two, too often slipping into decorative reflex.

It is precisely within this tangle of inherited codes and staged futures that a younger generation of artists, musicians, and collectives is working alongside Kurbanbaev, serving as counter-cartographers of a parallel Uzbekistan. Underground raves double as cultural fundraisers, conversations stretch into collaborative projects, and alternative education initiatives fill gaps left by formal systems. Small-press zines are stitched together in shared flats, and site-specific interventions vanish with the event but remain in the city’s memory.

From within this network of spaces and practices, questions of our past are never abstract, but embedded in the very act of making. These are heterotopias layered in contradictions and fluidity. They are not counternarratives in the sense of pure opposition; they are an insistence on the in-between, on living inside contradiction and treating it as material rather than a flaw to be resolved. The challenge and the work that some of us are trying to do is find a conceptual language that neither neglects the Soviet imprint nor lets it dictate the frame, treating it as one layer among many while insisting on other ways forward.

Kurbanbaev’s photographs sit inside this cartography, holding together multiple temporalities without forcing them into one story. Soviet traces persist without nostalgia or fetish, traditional forms surface without being framed as folklore, and the contemporary moment asserts itself without erasing what came before—always in dialogue with the layers that shape it. This coexistence feels unforced. Rather, it’s a result of looking at Uzbekistan not as a static identity to be defined, but a living archive that Kurbanbaev is constantly rearranging in the first place.

The photographer resists the impulse to compress these layers into a single narrative, letting them overlap, contradict, and refract through one another instead. In doing so, he offers an image of the country that is both specific and very ambiguous—one that mirrors the way cultural memory, lived experience, and inherited aesthetics actually function in everyday life.

“I think that photography is a good way to represent your space, community, and communication with the outside world. Long-term projects can not only help you navigate and explore, but also become a storyteller for those who may not be familiar with my country,” he says. “Now is the time for stories from Uzbekistan, Central Asia, created by artists from here.”

For so long, people in our region have been treated as subjects to be studied—looked at, written about, archived. Now, while it seems like a more substantial wave of interest in Central Asia is sweeping in, this time promising a dialogue, it has often circled back to the same extractive logic. Defining how this generation of artists and thinkers works are questions of who gets to speak, whose knowledge counts, and how marginalised voices (whether women, non-heteronormative, or ethnic groups such as Uyghurs) are positioned. As Kurbanbaev puts it, “Understanding that, like other local photographers, we are trying to convey our point of view or make the country visible in the field of global photography. It also helps in my work—for me, the simplest topics say a lot.”

That drive to speak from within threads through Davra Collective, a creative feminist initiative that reclaims agency over how knowledge about Uzbekistan is produced and circulated. It treats research as a public, lived process, not an academic exercise—a stance Kurbanbaev echoes when he describes how his own research principle is most often dictated by intuition, and most often lives outside the time frame. “This feeling, this sensation, of what I want to know, what I want to tell is connected with myself, cultural identity, how close I am to my roots.”

That way of rooting questions in lived experience rather than imposed frameworks is what allows collectives like Davra to bring archives, oral histories, and contemporary practice into the same frame, resisting narratives imposed by outsiders. Rather than operate as fixed institutions, they shift fluidly with the needs of their participants. Such a rejection of linearity and hierarchical cultural structures is a defining moment for Uzbek youth. Take Maqaal, sitting at the intersection of publishing, translation, and discourse-making.

The collective often works in Indigenous languages, producing educational materials and hosting talks, screenings, and workshops that carry its themes into public spaces. Maqaal’s publications bring together essays, interviews, and visual works that avoid framing the country through a tourist lens or as an exoticised ‘other’. By connecting local and regional contributors, it positions itself as both an archive of the present as well as a space for experimentation. Bringing indigenity back into the discourse, such collectives resonate a clear decolonial intent that echoes equally in Kurbanbaev’s work, where a rebuttal to colonial narratives lies under the logos and subversion of kitschy aesthetics.

This DIY cartography matters because it shows a different way of holding the past and present without collapsing into either costume, and without ceding the right to define what is worth keeping. It does not cancel the official script or the lavish promise; it runs alongside, providing a critical angle while moving on its own terms. The ‘now’ is one of urgency and rebellion to seize back the right to narrate, to create with the end goal of liberating local youth through a genuine counterculture, mapping a new Uzbekistan outside institutional narrative bounds. Here, cultural memory and lived experience belong not to state scripts or external observers, but those telling the stories from within. “Today’s Uzbekistan is a country with a history, where there are many different pages, good and bad,” notes Kurbanbaev. “It is a place for reflection, some analysis, and personal participation in the creation of new stories. And I know that no one except us can create these stories—some through words or music, and others through photography, like me.”