Posted in

Art & Photography,

Posted in

Art & Photography,

In Tala Madani’s latest London exhibition, her iconic figure “Shit Mom” enters the age of AI

Text Vamika Sinha

Since 2019, Iranian American artist Tala Madani has been painting a memorable recurring figure: “Shit Mom”. She is – you guessed it – full of shit: a personified smear of fecal matter who leaves a stain on all she encounters. She is the antithesis of the ideal woman: dirty, disgusting, shapeless, messy, and disobedient. Or, in other words, bad at her job –– the various roles demanded of her to thrive as a 21st-century woman.

As social critique, “Shit Mom” is genius, a fugitive being who is also funny and playful. Satire rises from her like steam off a fresh dump, depending on how Madani animates her on the canvas and occasionally on video. There is no preachy, kitschy feminist symbolism or language; the figure is a mutable conduit for nuanced narratives about womanhood, while innately resisting its ideals.

In her latest exhibition, Daughter B.W.A.S.M at Pilar Corrias London, Madani steers “Shit Mom” into new ideological territories, namely the unbridled rise of artificial intelligence. She gets an adoptive AI robot daughter, the antithesis to the antithesis (B.W.A.S.M stands for “Daughter Born Without a Shit Mom”). After all, both mothers and AI cannot exist, in the truest sense, without a relational other. So what happens when the pursuit of extreme knowledge and perfection meets her flawed resister –– who must also be her guardian?

It isn’t difficult to imagine an AI daughter when thousands have made machines their proxy therapist, assistant, friend, mentor, or lover. This is where Madani’s activation of “Shit Mom” takes a wider, more complex view, transposing its previous concerns around motherhood, bodies, and feminism onto vaster anxieties about the normalisation of AI, and humans and machines becoming more co-dependent. I am reminded of Jia Tolentino’s 2019 book Trick Mirror: “Figuring out how to ‘get better’ at being a woman is a ridiculous and often amoral project –– a subset of the larger, equally ridiculous, equally amoral project of learning to get better at life under accelerated capitalism.”

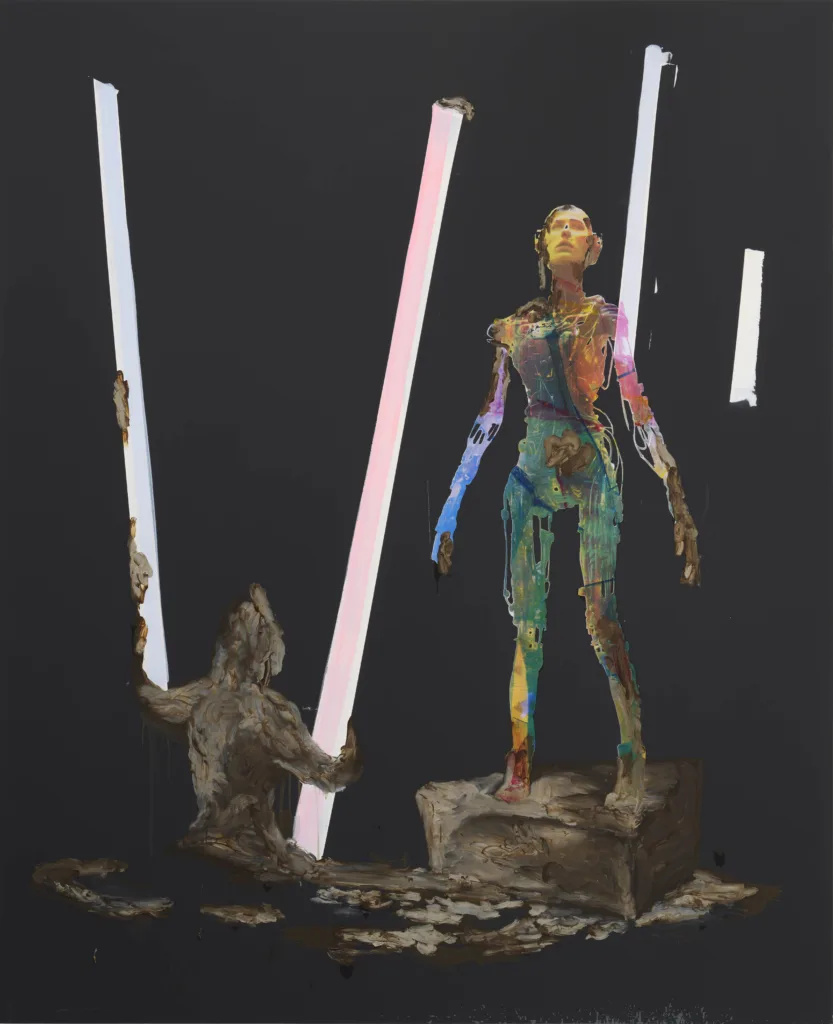

The AI daughter in Daughter B.W.A.S.M is often AI-generated and screenprinted onto the canvases, while “Shit Mom” is painted leaky, streaky, and almost monstrous-looking in comparison. The depictions of light are especially eerie and enchanting, as if glowing from within, like a cellphone illuminated in the dark. In a few works, “Shit Mom” holds a soft, pastel teddy bear; but it’s as if her shittiness rubs off. The teddies are slightly slimy and sloppy, the attempt at care or connection with the ‘daughter’ messier than intended. In another painting, “Shit Mom” makes two AI daughters literally lose their heads. The fallibilities of being human seep like osmosis in D.B.W.A.S.M. (Pink Teddy) (2025) through a screen’s hard black edges into the very structure of the daughter. She looks beautiful, appearing as half tech, half silvery-white dripping liquid, a magical, otherworldly cyborg. She is, in other words, touched.

In her 1985 text A Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway describes the cyborg as a “hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction”. She remarks how “disturbingly lively” our machines have become and “we ourselves frighteningly inert”, eager to transfer our agency to someone or something else. Women, Haraway argues, who are so deeply entangled in and quashed by society’s ‘machinery’, can rather choose to embody a cyborg feminism: becoming radical, hybrid beings who make the boundaries between human and machine, nature and culture, man and woman, more fluid and leaky.

After all, it is us “shitty” humans who create, shape, and influence who and what AI gets to be. We are its custodians. Madani’s explorations of the above binaries form her own cyborg feminism. When you put this literally fluid, solitary woman and her adopted AI robot daughter together, you make great art out of a very pointed middle finger. “Illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins,” Haraway writes. “Their fathers… are inessential.”

Speaking of lineage, Madani was inspired by Francis Picabia’s Fille née sans mère (Daughter Born Without a Mother), a 1916 painting on top of a steam engine illustration. Picabia was interested in increased American enthusiasm for mechanising society, his title further referencing the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib and the Virgin birth. Making the engine a “metaphor for human life”, Picabia implicitly positioned the woman’s body as a mythical yet optimising reproductive machine.

Madani recreates Picabia’s work as a painting and an installation in the centre of the exhibition. They’re the least gripping works (and it’s hard to understand them without picking up the text), but they are, literally and metaphorically, the show’s engine: if we’re going to talk about feminism and womanhood in the age of AI, we have to look back to see how we got here.

Madani nods to other older male artists: Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase sneaks into several works, like Shitmom Ascending a Staircase (2025), where “Shit Mom” melancholically comes down the stairs while staining the walls. It’s incredibly satisfying that this work appears right when you descend the stairs to the lower gallery floor. Meanwhile, in S.M. Ascends (2025), “Shit Mom” gets Sisyphean as we see her endlessly go up a staircase, the scene resetting every time she gets to the top. The video works riff on early motion studies by Eadweard Muybridge. “Shitmom Learning How to Walk” (2025) places his footage of naked women – recorded doing different movements – next to an animated “Shit Mom” who falters at imitating their actions, constantly collapsing into a pile of waste.

Daughter B.W.A.S.M finds resonance with Dirty Looks, a major exhibition on at the Barbican that examines fashion’s historic relationship to ‘dirty’ aesthetics. One of its texts quotes philosopher Julia Kristeva: “it is not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order.” Against the female body’s long association with “virginity, passivity, and purity…dirt suggests activity, agency, autonomy and impurity.” As with “Shit Mom”, the curators see dirt as a subversive force, one that “amid the increasing digitisation and dematerialisation of culture” returns in many forms today within “disobedient figures and ideas pushed to the margins of industrialised society.” “Shit Mom” is a perfect embodiment of this imperfect group.