Posted in

Art & Photography, Misan Harriman

Posted in

Art & Photography, Misan Harriman

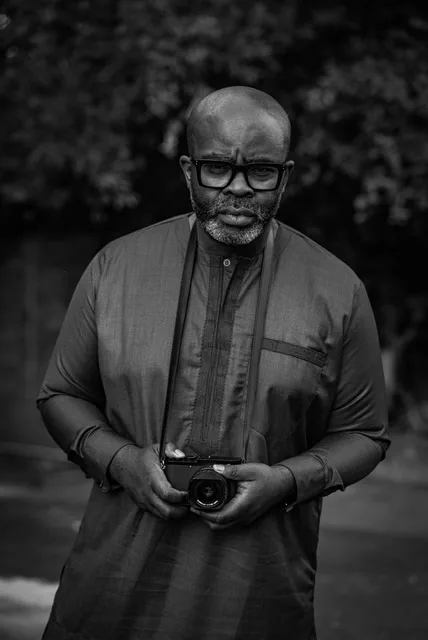

Misan Harriman on photography, Palestine, and the ongoing project of decolonisation

Text Selma Nouri

“Photography, like protest, is about bearing witness,” says Misan Harriman. By capturing a moment, or freezing fragments of individual and collective humanity, the image resists; it stands in direct opposition to the project of erasure. “To say, I may not know your story, but I see your struggle…at a time when polarisation is often the loudest voice in the room, that kind of empathy is in itself a radical act.”

As I reflect on Harriman’s words, it is his use of the term empathy that stays with me. In a moment marked by apartheid and the continued killing of innocent Palestinians, we are confronted with a profound rupture in our collective moral consciousness, one that leaves us increasingly estranged from our shared humanity. Empathy, once seen as a basic human instinct, now, as Harriman suggests, bears the weight of radicalism. “To feel, in itself, is to resist,” he says.

As a leading photographer of protest and collective resistance movements, Harriman’s practice profoundly illustrates the transformative power of solidarity. “It is easy not to care when a crisis does not touch your doorstep,” reflects the Academy Award-nominated filmmaker and photographer. “But the true moral arc of humanity is revealed when we stand with people even when we don’t have to, when their pain is not ours, yet we carry it anyway. This is the quiet power of photography. It builds bridges between strangers, between nations, and between struggles that may appear different but are fundamentally rooted in the same fight for dignity.”

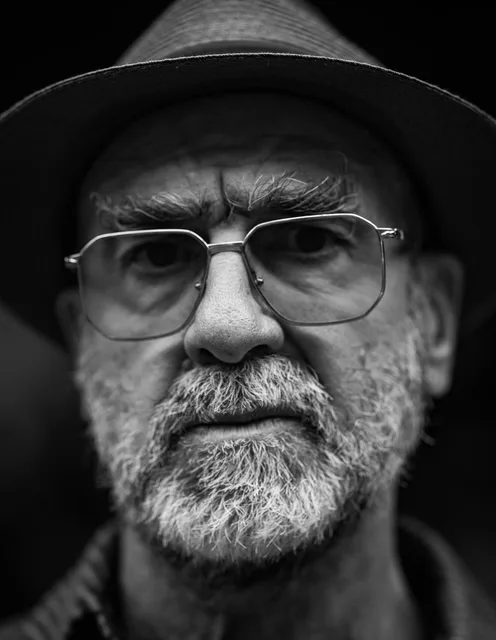

Although Harriman only began his journey as a photographer at the age of forty, he has, in a remarkably short time, expanded the very conceptual boundaries of the medium. Refusing the constraints of both archival documentation and aesthetic commodity, his work reclaims the image as an urgent and affective form, one that engages the immediacy of the present as powerfully as it bears witness to the past.

“When I photograph protests, I bring nothing with me but a backpack and my camera,” he says. “I don’t need elaborate equipment or a team; the only thing I am searching for is truth, and truth should never be a needle in a haystack. When people are confronted with truth, they embark on their own process of recognition. Perhaps that is why my images resonate – they resist denial. Because all I am revealing are human beings pouring out their solidarity. At times, their rage…their humanity. I am freezing those intimate moments of human expression in time.”

Such a vision, I believe, requires much more than technical skill; it demands an innate capacity for care, an ethical disposition inseparable from aesthetic intent. Harriman’s oeuvre reveals that this sensibility is rooted not only in his artistic practice but in his entire being. He perceives humanity with a depth that transcends observation, embodying the very sense of empathy that his images so powerfully evoke.

“Before photography, I didn’t really know who I was,” Harriman reflects. “I struggled to find my voice – not just as an artist, but as a person trying to make sense of this crazy world. When my wife gave me a camera for my fortieth birthday, she saw something in me that I couldn’t see for myself. Her love opened up a path toward self-recognition, allowing me to rediscover my passion for storytelling and, perhaps most importantly, to understand myself as a child of empire…shaped and burdened by that history but also deeply empowered by the truth of it.”

There is a particular complexity, or a distinct power, in confronting one’s position within the enduring legacy of empire. Both of Harriman’s parents were born in what is now recognised as an occupied Nigeria, a history that indelibly shaped his understanding of the profound power and potential of collective resistance. “You know,” he reflects, “the British often use the word colony to describe their history in Nigeria. But what is a British colony? It is a place that has been occupied, right? So when occupation literally runs through your blood – when you begin to understand what your people have endured, or when, as a child, you watch Nelson Mandela raise his fists to break the chains of apartheid in South Africa, you begin to grasp the immense power…or rather the duty, we each have in restoring our shared humanity. Once you recognise that, it becomes almost impossible to do anything else. At least, that’s how it was for me. When I discovered photography, I knew immediately what I had to devote my life to.”

In 2020, Harriman’s life changed overnight when Martin Luther King III shared several of his photographs from the Black Lives Matter protests. The images went viral, catapulting his work into the global spotlight. “My entire life exploded,” he recalls. “Suddenly, I had a platform to share my work.” Within months, Harriman made history as the first Black photographer to shoot the cover of British Vogue, and notably, its prestigious September issue. The recognition ushered in a wave of major opportunities, from portraits of Rihanna to Meghan Markle’s pregnancy announcement, expanding his portfolio of iconic images and cementing his place among a new generation of photographers redefining contemporary culture.

Yet with success came a deeper reckoning. “I had a choice,” he says. “I could have spent the rest of my life photographing celebrities and red carpets…But no matter how much commercial success I achieved, I knew that would never be enough.” Harriman’s purpose has always been rooted in protest, in documenting and bearing witness to movements too often dismissed or misunderstood. Today, he dedicates his practice almost entirely to these struggles, rarely missing a chance to capture the humanity that arises from collective resistance.

“How can we pass each other like ships in the night when the world is on fire?” he asks. “Every day, I wonder, what can I do with my lens to help put out that fire? How can I use it to build bridges or to soothe the inherited trauma that so many of us, children of empire, still carry? How can I help white men and women recognise the privilege and unconscious biases shaped by white supremacy…or by the hyper-extractive capitalist world we are forced to live in? Amid so much heartache and suffering, I have chosen to make my sword and shield my lens and my voice. That is precisely why we are speaking today.”

Harriman recalls a quote by Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank. “The eye must learn to listen before it looks…I always come back to that line,” he says, “because my eye had been listening for a long time before I had this seemingly inanimate object [a camera] placed in my hands. That’s probably why everything took off the moment I started taking pictures. I was ready. I had lived and seen enough to know exactly where to point the lens.”

You can sense this the moment you encounter Harriman’s work. A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of visiting his exhibition The Purpose of Light at Hope93 Gallery in London. Due to popular demand, the show has been extended until January 8th, 2026, and I strongly encourage anyone in London to see it.

Even before stepping inside, I stopped short beside other strangers, all of us gathered silently at the gallery window. Momentarily suspended, we were drawn to a striking black-and-white photograph mounted against a plain black wall. In the image, a rabbi and an imam stand side by side, holding a sign that reads “Save Gaza.“ In that instant, I felt the profound weight of what awaited inside.

From the images of families mourning the Grenfell Tower fire to the singular, almost angelic portrait of Francesca Albanese, there is something immensely moving about Harriman’s work – an unflinching eye for humanity paired with a gentleness that seeks no attention. His conviction is unequivocal. “I still don’t understand,” he says, “why every photographer, no matter their focus, isn’t bearing witness. We have just lived through our Vietnam. We have lived through one of the greatest atrocities of our time…If you have a platform, you should be doing everything you can to protect all kinds of communities.”

For Harriman, the point of departure is the indivisibility of human experience. What happens to one of us, he suggests, inevitably reverberates across the collective, and his photographs visualise this interconnectedness with remarkable clarity: Holocaust survivors expressing solidarity with Palestine; members of the Palestinian diaspora mourning victims of racial violence; queer communities aligning themselves with broader decolonial and liberationist movements. Through these visual dialogues, Harriman reveals the structural continuities that bind ostensibly disparate forms of oppression. From the climate catastrophe to colonial violence, his work insists that no system of power or privilege ever remains insulated from the suffering it produces.

“That is exactly what I want people to understand,” Harriman says. “The demon at the top of what is going on in Palestine is the same one fueling the hellscapes in Sudan, Congo, Haiti, and Yemen. It is the same patriarchal, hyper-violent, capitalist, neocolonial framework that forces us to fight for collective liberation around the world…So many people break down in tears when they encounter my work, including many men, because the images make visible how deeply connected we all really are. When you see photographs of the Grenfell protests beside those of Palestine, you begin to understand that it is the same greed…the same folly of man, that allowed people to burn alive in central London while children are being sniped by grown men in Gaza.”

And it is precisely the role and responsibility of the artist to offer this kind of perspective, Harriman argues. “When so much of the conversation is fueled by rage, I want my work to encourage critical thinking…I want to take people off that island of anger and guide them onto a path where they can join hands with communities that help them see more clearly. Sometimes that means embarking on a journey of unlearning or, if necessary, completely decolonising your mind. Unfortunately, however, few in the art world are willing to speak openly about anything beyond the mainstream. Issues like anti-Arab hate, toxic patriarchy, or extractive capitalism rarely appear in major exhibitions. It’s a sad reality,” he insists, “one that makes clear how much systemic work still needs to be done. As Nina Simone once said, art should reflect the times we live in. Anything else is just entertainment…And I have no interest in entertaining people when the world is on fire.”

While escapism certainly has its place, “your entire life cannot be just that,” Harriman insists. “Otherwise, we will gallop collectively toward oblivion, and apathy will dominate our entire understanding of the world,” a prospect that already feels uncomfortably close. This dynamic, he suggests, is particularly evident in the reception of his own work. Despite the popularity and emotional resonance his Palestine protest imagery has generated online, he notes that, unlike his BLM photographs, these images have been completely absent from mainstream news coverage. “The liberation of Black lives, the queer community, climate activism,” he says, “all of those issues are now acceptable to most progressive liberals. So in 2020, when my BLM photographs were first published, they happened to align neatly with the prevailing narrative. My Palestine protest photos, on the other hand, do not operate within the same landscape of performance – or, more precisely, they do not serve Western interests. No major outlet would dare show such emotional or humanising depictions of a movement directly challenging the underlying structures of Western imperialism. Palestine is the one issue that makes everyone malfunction.”

He refers back to his photograph of the rabbi and the imam as an example. “It’s the most embarrassing image for mainstream media because it directly challenges the narrative we have been fed for years…Here are two men who are supposedly meant to hate each other, standing side by side on the streets of London like brothers, pleading for the annihilation of babies to end. How extraordinary is that? But it runs completely counter to the Western narrative – counter to the propaganda they choose to uphold – so they would never, and probably will never, show that image on TV.”

“But why Palestine?” I ask. “Why is that the issue where so many progressive liberals seem to draw the line?” Harriman responds without hesitation: “Because Palestine is the source code of the last functioning imperial project…I am not sure if you know much about Star Wars, but someone recently described the liberation of Palestine as a single shot through the exhaust valve of the Death Star. It is the movement capable of collapsing the entire imperial system. If we liberate Palestine, we liberate ourselves. We liberate every remaining project of empire, including Sudan, Congo, and Haiti…It would dismantle, or at least fundamentally destabilise, the neo-colonial order that insists violence and profit-driven militarism are the only viable routes to peace.”

His point, ultimately, is that the stakes of Palestine exceed the specifics of any single geopolitical struggle. Although certain liberal positions have gradually been absorbed into the broader architecture of capitalist exploitation and Western imperial power, the liberation of Palestine demands something far more disruptive – a complete decolonisation of the mind. “It would erode the imperial logic that reduces the Arab man or woman to either a wealthy fool or a violent terrorist,” Harriman argues. “The same logic that co-opts Black culture and then weaponises it, turning Blackness itself into the enemy. That has always been the structural instrument of white supremacy, and Palestine is a wake-up call…I mean, that is why you see keffiyehs at trans marches, BLM protests, and ICE demonstrations. People have finally realised that we are all fighting the same enemy, the same system of imperial domination.”

Building on this imperative, Harriman acknowledges that there remains significant potential to expand and strengthen networks of solidarity across communities. “I wish that Congo and Sudan, in particular, would engage more visibly with the pro-Palestine movement. Their protests have been much smaller, which is frustrating. Of course, this disparity arises from differences in scale and organisational capacity, but it also reflects the internal biases that continue to shape every community.” Despite the considerable progress achieved since 2023, the project of decolonisation remains far from complete. “We all still have work to do,” he says, and that is precisely why sustained public protest and community mobilisation remain essential.

“We cannot stop until we see the full liberation of Palestine,” Harriman insists, “until we see an end to apartheid and settler-colonial domination. Israel operates as an illegal occupying power, maintaining one of the most advanced systems of racialised violence the world has ever witnessed. This is not a matter of opinion, but a conclusion grounded in extensive evidence and historical documentation. In 2025, Palestinians are still barred from driving on certain roads and must pass through six or seven checkpoints just to reach work. They are imprisoned without trial and forcibly removed from their homes. This is a system rooted fundamentally in white supremacy…given such a reality, how can I – as an anti-racist, an artist, or simply a human being – be expected to focus on anything else?”

In this sense, Harriman’s practice exemplifies art’s capacity not merely to document but to endure – to bear witness and to provoke reflection and transformation in ways that transcend the limitations of both time and circumstance. Between the highlights and shadows of his images, he gestures toward the very essence of truth. “There is no test run for my photographs,” he explains. “You never know what you are going to get – standing in rain, snow, or harsh sun with thirty kilograms of equipment on your back and half a million people walking toward you. It’s a form of fine art…one that I believe tends to outlive the artist. They can never destroy every picture I have taken. They cannot hide them all, especially in the tumultuous times we are living through.” Genuine relief will emerge only when we confront and dismantle entrenched systems of injustice. In the meantime, he reflects, “I want everyone my images have represented to know that there at least existed a community that tried, one that, I am certain, will ultimately succeed.”

A Note from the Writer:

This piece on Misan Harriman’s work was written before the United States’ illegal capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. As events continue to unfold, and as international law is once again subordinated to Western and extremist geopolitical interests, the central message of Harriman’s photographs has only grown more urgent. His images do not merely document protest; they articulate a broader political truth about the interconnectedness of contemporary struggles against imperial violence. They point toward what I believe remains the only durable source of hope for the future…human connection.

As Harriman notes, when his images of the Grenfell protests are viewed alongside those of Palestine, it becomes clear “that it is the same greed…the same folly of man, that allowed people to burn alive in central London while children are being sniped by grown men in Gaza.” That same logic now underpins the illegal attacks against Venezuela. These are not isolated tragedies but expressions of a single imperial system, reproducing violence across borders and contexts.

U.S. public funds continue to finance Israel’s war crimes while citizens at home struggle to secure housing, healthcare, and basic safety. A century of coups and forced regime changes in the MENA region and Latin America has produced not stability, but enduring violence, mass suffering, and global insecurity. Harriman’s work confronts viewers with this reality, insisting that distance does not confer exemption. Our lives are inseparable, no matter how far removed we imagine ourselves to be. Yet, for too long, the burden of naming and resisting imperial violence has fallen disproportionately on the Global South and its diasporas. This responsibility cannot remain theirs alone. And freedom, we must recognize, cannot exist selectively. To ignore one instance of imperialism is to remain complicit in all of them.

This is why Palestine remains so central – or the “source code,” as Harriman describes it – of the last functioning imperial project. Until we collectively acknowledge that suffering is structurally interconnected, and that calls for Palestinian liberation reverberate across every site of imperial domination, genuine emancipation will remain impossible.

Clearly, decades of apartheid and the genocide in Gaza have emboldened the U.S. and its allies to act with total impunity. Whether the public still believes its narratives of human rights and liberalism no longer matters. Those myths have already collapsed. What Harriman’s images insist upon now is not merely political clarity, but how that clarity is mobilised – how knowledge is translated into sustained, collective action.

No political order can endure indefinitely on hypocrisy, inequality, and falsehood, and we are witnessing that unravelling in real time. We must, therefore, continue taking to the streets. From Palestine to Venezuela, we must fight for all of us. Liberation, if it is to be meaningful, must be pursued collectively – or it will not be achieved at all.