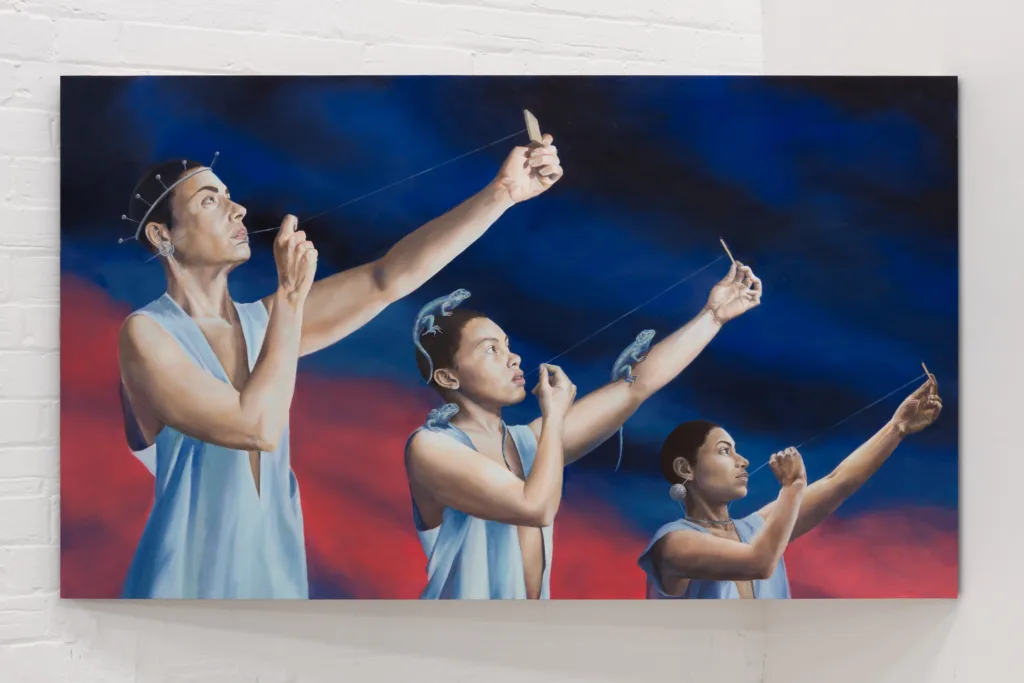

Sarah Al-Sarraj, The Dog Tooth of Time, 2024. Oil on wooden panel, 175 x 308 cm. Photography by Jules Lister.

Posted in

Art & Photography, Exhibition

Sarah Al-Sarraj, The Dog Tooth of Time, 2024. Oil on wooden panel, 175 x 308 cm. Photography by Jules Lister.

Posted in

Art & Photography, Exhibition

Limbs of the Lunar Disc: Sarah Al-Sarraj reimagines ancestral justice across collapsing timelines

Text Yasmin Alrabiei

When I meet Sarah Al-Sarraj in her Lewisham studio, she refers to the figures in her large-scale paintings on wooden panels, as people, and I follow suit. The series follows the lifeways of a mythical nomadic tribe that travels through time to preserve biodiversity. They fracture across eras, with Ancestors and Descendants aching for reunion while separated by millennia.

Her forthcoming solo exhibition, Limbs of the Lunar Disc, curated by Jessica El Mal, blends Indigenous and esoteric wisdom with science fiction. It is worldbuilding beyond the Western canon, asking what futures might emerge if we unhook time from empire and ecological violence, attuning instead to the murmurs of soil, stars, and memory. The show, opening at Mimosa House on 22nd May, is co-commissioned by Shubbak Festival and the Arab British Centre. It honours your ancestors and mine, and reaches toward those who, at some cosmic hour, will call us theirs.

Mechatronic Library.

This temporal entanglement is rooted in the idea of the ancestral assemblage, a concept coined by theologist Laura Nasrallah, which rejects the notion of time as a linear thread, severing us from those before and after. Al-Sarraj’s work is in conversation with that idea, traversing time as though it’s a landscape. She understands that solidarity can stretch vertically, across centuries; that compassion can move through the strata of ancestry and descendancy.

Across each painting, Al-Sarraj makes visible the quantum entanglements between bodies, landscapes, and histories. Her paintings begin at a rupture: the extinction of the Barbary lion, once native to Iraq, an apex predator whose disappearance triggers a trophic cascade, unravelling the balance of the ecosystem. This ecological collapse rearranges the timeline, and so in the central landscape, The Dog Tooth of Time, Al-Sarraj imagines a sunrise ritual performed by the nomadic tribe, grieving the lion’s extinction.

Jules Lister.

Islamic science is a clear compass in Al-Sarraj’s work, especially Surah Al-Kahf, where young persecuted believers sleep for 300 (and 9) years, contorting time itself. This slippage between lunar and solar calendars reveals the elasticity of sacred time, a theme Sarah reveres. “The Qur’an is full of these references to deep time”, she says, adding her inspiration from “environmentally conscious ways of thinking drawn from Islamic esoterism.”

In Al-Sarrajs’ new immersive film, Isthmus Ancient River, commissioned by visionary worldbuilding curator Helen Starr’s Mechatronic Library, the viewer travels the river of time to a crumbling version of the apartheid wall, standing in the West Bank today, and marked by graffiti commemorating George Floyd. That this present-day architecture of violence has deteriorated in the timeline of the film demonstrates an emblem of collapsed ideologies. It echoes the adage: the world is littered with the ruins of empires that thought they would last forever.

Mechatronic Library.

The film is constructed with Unreal Engine, a game engine often used in high-fidelity gaming. But she isn’t interested in realism. “It’s a poetic software,” she says. “You can have a river speak, a tree tell a fable. I get to decide not just what vegetation exists in this world, but how my people interpret time.” Most software mimics real-world physics, but with Unreal, Al-Sarraj can simulate a world based on her own temporal laws.

Though Al-Sarraj’s work is anchored in speculative themes, it never drifts into abstraction. In conversation, she has a remarkable ability to render vast, conceptual ideas with precision and texture. Her reflections on time, for instance, feel closer in spirit to quantum science that transcends linear metrics of Western calendars. At the core of her practice lies a deep reverence for the specificity of Indigenous ontologies. Her work pulses with scientific rigour, where ecological motifs act as both method and metaphor, transforming research into something intimate and alive.

For example, ancient Arab navigational tools like the wood-and-string Kamal are depicted in the painting Time Reckoning. Held at arm’s length, the Kamal helps measure the angle between the horizon and the North Star, determining the latitude. “I’m focusing on this indigenous understanding of deep time. It’s embedded and embodied, and rejects the time ordering systems that have roots in colonial violence,” she says, referencing the origins of cartography and Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) in military expansionist motivations.

Lister.

Other semiotics of natural timekeepers recur throughout Al-Sarraj’s work: clams that open and close with the moon’s pull, monarch butterflies migrating across four generations by memory alone, and the resilient Tamarisk tree referenced in the Qur’an– each offering a poetic index of time rooted in biology, cosmology, and sacred tradition.

As an Iraqi in Britain, her understanding of exile lends depth to the hybridised reality she depicts– being equidistant from the deep future and the deep past. In 7000 Gaits Apart, two members of the tribe, one ancestor, one descendant, are distanced by centuries, not geography. They gaze at the same star, the only constant they share across ruptured timescapes. The sky becomes a shared map of longing and memory as they dwell on each other at polar ends of the timeline.

For those of us born into the aftershock of empire, time can feel like a broken inheritance. We ache for people we’ve never met. Al-Sarraj carves another route. This exhibition is essential viewing for everyone– but if you descend from a lineage ruptured by world events no one consented to, as so many of us do across this distorted map, its poignancy will strike you with rare immediacy. It certainly affected me, and still is.

Time was hyperreal in that room. I left Al-Sarraj’s studio at 9 pm after four insatiable hours of conversation. But it felt like I had crossed a threshold into another world. One where an artist had quietly bent the arc of time itself.