Posted in

Art & Photography, Art Prize

Posted in

Art & Photography, Art Prize

Right here, right now: Richard Mille and Louvre Abu Dhabi reshape where art belongs

Text Selma Nouri

In the language of art, few terms carry as much weight, or provoke as much contention, as the word ‘canon’. It operates as a silent arbiter of artistic memory, determining what endures and what recedes into obscurity within the evolving narrative of art history. To speak of the canon is to invoke a lineage of power and privilege—a carefully curated narrative of excellence that has, for centuries, dictated whose creativity is enshrined as exemplary and whose has been overlooked.

I was required to engage deeply with this canon during my undergraduate studies, analysing and venerating works ranging from Michelangelo’s David to the Parthenon. While these masterpieces undoubtedly warrant admiration and scholarly attention, I found myself questioning the distinctly western inflexion (or predominantly European and North American historiography) that has shaped this tradition. Why are these particular works and artists upheld as universal standards, while others, spanning regions from the Gulf to East Asia, remain marginalised or excluded from the broader narrative of global art history?

Although this question is by no means new, it has taken on renewed urgency in our present moment. We cannot rewrite the past, nor should we dismiss the western works that continue to serve as vital touchstones of artistic achievement. Yet we do possess the agency, and indeed the responsibility, to shape the future. By celebrating the diversity of artistic traditions worldwide – including those historically overlooked or marginalised – we can begin to envision a more inclusive canon, one that honours the breadth of past cultural contributions while redefining the present.

Through the annual Richard Mille Art Prize and Art Here exhibition, Louvre Abu Dhabi and Richard Mille have committed to this endeavour. Launched in 2021, the initiative has become a vital platform for both showcasing contemporary artistic practice in the Gulf and fostering cross-cultural dialogue across the broader east. Now in its fifth edition, it invites artists to submit works for inclusion in the Art Here exhibition at Louvre Abu Dhabi, with the prestigious Richard Mille Art Prize awarded to one outstanding artist. Past recipients (Nasser Al Zayani, Rand Abdul Jabbar, Nabla Yahya, and Nicène Kossentini included) embody the initiative’s commitment to championing diverse and innovative artistic voices, particularly from the SWANA region.

As Tilly Harrison, Managing Director of Richard Mille Middle East, explains, their partnership with Louvre Abu Dhabi was born out of a shared commitment to “championing the arts and celebrating creativity across the region”. She described the museum as one of the most respected cultural landmarks in the region, noting that its values align perfectly with Richard Mille’s philosophy, which is rooted in innovation and craftsmanship. “Together, we recognised the importance of providing a platform that not only honours established artists, but also nurtures emerging voices from the region. The Richard Mille Art Prize is, in many ways, the natural culmination of that shared vision.”

Each year, the Art Here theme is selected by the prize’s curator and, for the ongoing 2025 edition, the role is held by Swiss-Japanese curator and founding editor of independent publication Global Art Daily, Sophie Mayuko Arni. She invited artists to respond to the theme Shadows, a narrative of Japanese and GCC exchange exploring “the interplay between light and absence, visibility and concealment, and the layered dimensions of memory, identity, and transformation.” Reflecting the region’s dynamic creative landscape, this year’s edition received over 400 proposals from artists based in the GCC and Japan, as well as SWANA-based artists with connections to the GCC.

For Arni, being selected as this year’s curator was a significant honour, reflecting the prize’s commitment to expanding standards of artistic excellence beyond the western tradition. “I think we are living in a post-western world,” she shares. “Of course, we still operate within western codes, and the history we study is largely western. We tend to speak English or French. There is no escaping that. But the aim is not to be anti-western. While we can and should continue to draw inspiration from the west, cultivating an unapologetic east-meets-east dialogue is now just as, if not more, important than the traditional east-west exchange.”

She observes that, politically, countries like Japan and the UAE have gained substantial influence, offering an unprecedented opportunity for regional creatives to set new standards of artistic innovation, establish original prizes and curricula, and rewrite global art history in ways that position the Global South as the authors and arbiters of its narrative. “We have an incredible chance to shape a new kind of art scene,” she adds, one that moves beyond entrenched hierarchies by recognising our own creatives as the benchmarks of excellence.

This idea is poetically realised through Arni’s curatorial vision of Shadows and the GCC-Japanese exchange, emphasising how, in both cultures, it is often within these shaded or liminal spaces that the greatest depth of artistic achievement emerges. “I was deeply inspired by the architecture of both Japan and the GCC,” she explains. “Consider the rays of light beneath the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s dome or in other outdoor spaces across the region—the harsh sunlight has historically shaped architectural responses, from vernacular areesh structures made of palm fronds to modern reinterpretations of the mashrabiya.”

Both create patterns of shade along streets and buildings, offering protection and moments of respite. Similarly, in Japan, architecture has long been designed around shadows and the subtle interplay of light and darkness. In his seminal “In Praise of Shadows” essay, Japanese author Jun’ichiro Tanizaki writes, “We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and darkness, that one thing against another creates.”

This notion of protection through shadows recurs across both regions. “Darkness, or the nuanced perception offered by shadows, is not something to avoid but to embrace,” she explains. “When light passes through darkness, beauty emerges in dimness and subtlety—in the spaces in-between. Shadows, as explored here, are more than visual phenomena; they are emotional, architectural, and philosophical spaces of refuge. They mark the passage of time, suggest presence through absence, and offer moments of pause in an increasingly one-dimensional and often unsettling world.”

In light of recent global events and widespread human suffering, Arni says there is a shared resonance in the reverence for shadows and the reconnection they invite. “Through darkness, we open ourselves to discovery; through the transient, we access the timeless. In both Japan and the GCC, this enduring protection is grounded in a shared respect for humanity, humility, and culture.”

Having moved to the UAE in 2013 for her studies, Arni witnessed firsthand the deep cultural ties between Japan and the GCC. “In their traditional identities, both share a profound respect for community and craftsmanship, as well as a mutual admiration for excellence,” she observes. In recent years, Tokyo and Dubai may have become synonymous with LED lights and towering skyscrapers. Yet, despite these rapid strides toward futurism, both societies maintain a deep reverence for their cultural and religious heritage—an enduring connection that gives them a distinctive strength in the realm of art.

In fact, historically, the cultural exchange between the GCC and East Asia runs remarkably deep. “From the Silk Roads to the lasting influence of Islamic art and architecture, trade routes carried not only goods but also people, ideas, and aesthetic traditions, linking cities such as Jeddah and Bahrain to China,” explains Arni. “So rather than continually turning to the west, I have always thought, why shouldn’t we revitalise these historic connections and work together to build a more advanced and interconnected future, one that allows this eastern cultural dialogue to thrive once again?”

This perspective strongly shaped Arni’s approach while organising this year’s prize in collaboration with Richard Mille, broadening its scope to include participants not only from the GCC but also from Japan. “I distinctly remember when I first moved to the UAE, plans for Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and the Saadiyat Cultural District were already underway,” she recalls. “I could see the city, and even the wider region, starting to take shape as a cultural hub, a new capital for the arts. I was only a student at the time, studying art history at NYU Abu Dhabi while most of my peers were pursuing economics or engineering. But for me, it was obvious. You cannot invest so heavily in cultural infrastructure without eventually cultivating a thriving art scene. I knew it was only a matter of time. And Japan, I think, offers a powerful example of how traditional eastern culture can coexist with futurism without being overshadowed by or defined through western influence.”

As Arni proves, the east’s potential for beauty and innovation is limitless. Yet, for many artists, exhibiting their work in cities like Paris or New York remains the ultimate dream. “But why not Abu Dhabi?” she asks. “Why not Jeddah or Dubai? Why can’t these cities become the aspiration? This kind of exchange, as Richard Mille and Louvre Abu Dhabi are demonstrating, can empower artists on multiple levels, elevating both the quality and ambition of their work. Funding in Abu Dhabi is often generous, but access to certain materials or technologies can be limited. In Japan, it’s the opposite. Cutting-edge innovation is abundant, but financial resources are scarce. The key lies in fostering dialogue and mutual support.”

There is a profound sense of protection in this, a safeguarding of one another after centuries of diminishment and perceived inferiority. This, once again, ties back to the current theme of Shadows, highlighting the protection and growth that can emerge through a more connected art community across the east. “This year’s edition feels like a crossroads of multiple currents in the contemporary art world,” Arni explains. “It offers a glimpse into the future while reflecting the intensity of the present—a boiling point on the cusp of something transformative. Hailing from Pakistan, Palestine, Morocco, and Japan, the shortlisted artists have installed their work in Abu Dhabi simultaneously, attracting a global audience to engage with it firsthand. That, in itself, is a visionary act.”

Very few awards originate in the Gulf, and this prize demonstrates that we no longer need to wait for external validation from the west. “Artists and curators are now in a position to recognise talent from the region themselves, inviting the rest of the world to participate rather than dictate,” says Arni. “We create the awards and determine the winners. The world does not. This autonomy is profoundly empowering and, hopefully, this model will only continue to expand. Japan has now been included, and future editions may encompass an even broader range of eastern nations. More importantly, I hope this prize inspires other museums, institutions, and brands to support and invest in artists from the region, fostering a sustained and self-determined ecosystem for artistic innovation.”

Contrary to popular belief, a canon is not static; it is expansive and constantly transforming. In SWANA, this swell of movement is at a linchpin–writers, curators, and cultural institutions across the region are taking hold of the opportunity to collaborate in shaping a legacy far greater than any individual effort. “The Richard Mille Prize is only the beginning,” as Arni reflects. “The GCC is a land of endless possibilities. It is a charged region, situated between shadows and horizons. It feels as though we’re witnessing history in the making.” Through art, we have the opportunity to assert our place in the world, not merely as participants in global culture, but as its architects. Our turn to write the canon is now.

Hamra Abbas

The exhibition opens with Tree Studies, an installation by visual artist Hamra Abbas. Comprising intricate stone inlay sculptures, the work transforms botanical drawings of tree species from the UAE and her native Pakistan into enduring forms. Using her signature technique of lapis inlaid in lapis, Abbas explores the interplay of light and darkness, drawing on the stone’s vivid blue pigment and muted grey tones to evoke the ephemeral silhouettes of foliage.

Installed beside the Damascus Fountain in Louvre Abu Dhabi’s courtyard, its stones form a mosaic that articulates the delicate balance of shadows within the natural world. The work invites reflection on both the vitality and vulnerability of nature, highlighting the liminal space that connects the two. Its material composition, meanwhile, suggests that while humanity has the capacity to preserve Earth’s abundance, it also bears responsibility for its loss—a duality made tangible through the deliberate voids embedded within the mosaic. These absences function as both visual and conceptual pauses, drawing attention to the space between abundance and depletion and reminding viewers of the sustained care needed to maintain the fragile equilibrium of our environment.

“Abbas offers a more organic way of perceiving shadows, as elements that exist within and between living forms,” explains Arni. “Just as shadows emerge from buildings and modern architecture, they also dwell within trees and the living world itself.” Yet the shadows produced by lush nature endure only if we continue to nurture and care for the earth. In this sense, Abbas’ work calls on us to attend to these shadows as a means of sustaining the beauty of life—of trees, flowers, and their fleeting silhouettes.

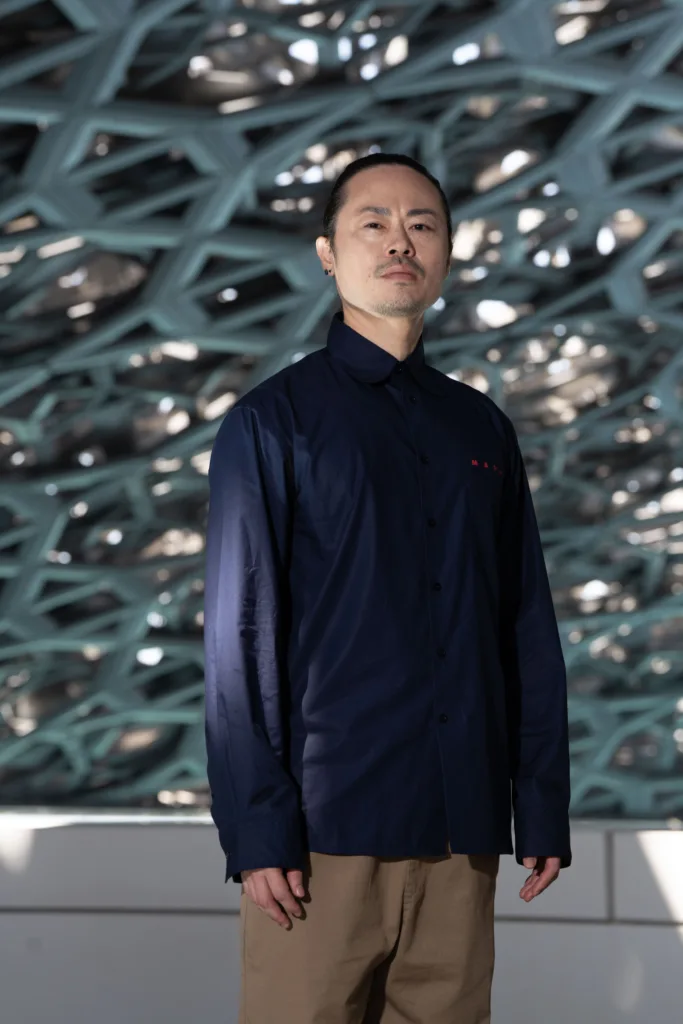

Rintaro Fuse

On the rooftop of the exhibition, Rintaro Fuse has created a sundial that traces shadows not only as measurements of time, but also as expressions of cosmic movement. As Arni explains, the work was conceived for a world at its beginning: “A world after the death of the sun, intended to preserve our imagination of a shadowless world, should we ever face a night that never ends.”

Crafted from stainless steel, the sculpture features three gnomons – upright poles traditionally used in sundials – aligned with different North Stars: Thuban (past), Polaris (present), and Vega (future). Each gnomon points along a distinct temporal axis, evoking a sense of ancient continuity. “Situated against the skyline of Saadiyat Island – an island of ideals both realised and under construction, oscillating between timeframes and geographies – the sundial becomes a quiet invitation to recentre ourselves in the present moment, to perceive the immensity and continuity of time,” she observes.

At first glance, the sundial may appear to mythologise the shadow as a cosmic notion. Yet its quiet power lies in returning our attention to the present, revealing the fragility and subtle beauty of this recurring, often overlooked phenomenon. “Shadows remind us that each day is new, offering, even amid the greatest hardship, opportunities for change and reinvention,” explains the curator. “Through the sundial, Fuse invites us to reflect on eternity not as permanence, but as persistence through absence.” While individual lives are finite, the ongoing interplay of light and darkness attests to the persistence of humanity. As long as the sun rises, there remains an enduring capacity for hope.

Jumairy

In Echo, Emirati artist Jumairy examines shadow as an intimate dimension of the self, offering a psychologically nuanced interpretation of the inner shadows we carry. This interactive installation, reminiscent of a desert well, draws upon the writings of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung as well as the myth of Narcissus. Its title evokes the cursed nymph Echo from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, whose voice, trapped in endless repetition, longed for Narcissus and ultimately became his shadow—a spectral presence that permeates the work.

Equipped with motion sensors, the digital well invites viewers to engage with their own silhouettes, which emerge in the gentle glow of LED lights, evoking a shimmering pool of water. As visitors peer into the well, they encounter not a fixed reflection, but shifting and ephemeral shadows of themselves. “Like a mirage beneath the water, it juxtaposes the seen and unseen,” observes Arni. “Jumairy creates a live dialogue between the self and the shadow self, guiding viewers towards an awareness and acceptance of dual identities.”

Through Echo, he suggests that the human self is shaped by shadows—simultaneously luminous and obscure, socially engaged yet solitary, subtle yet complex. And through deliberate introspection, one can apprehend the aesthetic and ontological significance inherent in both.

Ahmad Alaqra

Palestinian artist and architect Ahmad Alaqra’s sculptural installation I remember. a light explores shadow as a medium of memory and preservation. The work is composed of translucent resin cubes arranged on shelves, each containing a 3D form of a shadow digitally modelled from photographs taken by Alaqra in Sharjah and Dubai.

Described as “both recollection and structure,” the shadows honour the subtle interactions and fleeting visuals overlooked in everyday life, from the shadow cast by a stairwell’s edge to the dappled patterns created by palm trees. “From a distance, the installation evokes the impression of a curated archive or library,” explains Arni. “Yet upon closer examination, it reveals intimate moments rendered immutable as light and shadow are materially preserved within the cubes.”

Positioned within a broader sociopolitical context, the work becomes a meditation on the politics of presence and the affirmation of existence, expressed through both collective memory and its tangible forms. As viewers move through the installation, these shadowed traces of memory and human experience are activated, functioning as evidence of life. “The work invites reflection on light not merely as illumination, but as encounter,” she adds. By preserving memory, however distant or shadowed, existence is affirmed. Memory itself becomes proof.

Yokomae et Bouayad

Yokomae et Bouayad is a design partnership founded in 2023 by Japanese architect Takuma Yokomae and the Moroccan architect Dr Ghali Bouayad. Their cloud pavilion installation comprises dozens of vertical, ultra-thin columns, each capped with steel mesh. As visitors move through the pavilion, the umbrella-like forms shape a variety of evolving spatial experiences, producing a constantly shifting interplay of shadows—entirely without any mechanical intervention.

The artists draw particular inspiration from the natural movement of shadows, especially those cast by clouds and tree branches. This influence is evident in the clustered formation of columns, which sway gently in the Abu Dhabi breeze. Arni describes the installation as “an oasis of ever-moving shade,” emphasising how the shifting angle of sunlight and subtle variations in weather cause the shadows to transform continuously, depending on the viewer’s perspective. “The shadows created by the pavilion are constantly changing, just as shadows move and shift with the clouds, so viewers never experience the same moment twice,” observes Arni.

On one level, the installation can be seen as a meditation on clouds and the transient nature of shade. On a deeper level, it reflects the evolving rhythms of life itself, the alternating patterns of light and darkness, the interplay of exposure and shelter, and the constant flux through which we navigate our existence. In this context, shadow emerges as a metaphor for the fragile and ever-changing beauty of the human experience, where nothing is ever entirely black or white. “The shadow is ephemeral,” she adds. “The shadow is fragile. And the shadow is change.”

Ryoichi Kurokawa

As Arni explains, Japanese audiovisual artist and composer Ryoichi Kurokawa “takes a more abstract approach by capturing the ephemerality of shadows”. His installation skadw- unfolds as an immersive spatial experience. Visitors traverse a long, dark corridor, their path guided by a piercing ray of light streaming through a floor-to-ceiling slit. Gradually, the light diffuses into a soft veil of fog, transforming the space into an ethereal passage. “This walk is a meditation on the Japanese concept of Ma, the interval or in-between space where viewers encounter a dynamic interplay of light and shadow that oscillates between presence and absence,” notes the curator.

Accompanied by a meticulously synchronised soundtrack, the work orchestrates a dialogue between sound and illumination. Each light source is independently controlled for brightness and hue, producing continuous fluctuations in the shadows cast onto the fog. In this choreography, shadow becomes not merely a byproduct of light, but a palpable presence, something felt yet perpetually elusive. It gestures toward the often overlooked beauty that resides in emptiness and impermanence.

By embracing transience, Kurokawa’s work provides a quiet reprieve from the pressures of constant engagement, inviting viewers to discover sanctity in stillness and reconcile with hope. He reminds us that, like shadows, peace often appears in fleeting intervals, residing equally in moments of abundance and solitude.