Posted in

Art & Photography, Lebanese Civil War

Posted in

Art & Photography, Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War, Through Patrick Baz’s Lens

Text Ahmed Amin

The Day that Ignited Years of War

Nearly 50 years ago, one of the most violent conflicts in the region’s history erupted in what was once called “the Switzerland of the Middle East.” It claimed more than 150,000 lives, displaced around 800,000 people, and left millions questioning their identity, beliefs, and sense of self.

April 13th, 1975. In Beirut’s Ain al-Rummaneh district, just outside al-Sayyida Church, an assassination attempt carried by the Arab Liberation Front targeted Pierre Gemayel, leader of the Christian Kataeb Party. Gemayel survived, but several of his companions were killed. Only hours later, Kataeb gunmen opened fire on a bus carrying members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command, on their way to the Tel al-Zaatar camp. Twenty-seven were killed. The attack, later known as the Bus Massacre, ignited a chain of violence that quickly spiraled out of control.

As news spread, clashes erupted between Palestinian and Kataeb militias across Beirut, and soon throughout the entire country. What began as a single confrontation evolved into a full-scale civil war, one that would split Beirut in two: West Beirut, largely Muslim and aligned with leftist and Palestinian groups, and East Beirut, predominantly Christian and controlled by right-wing factions.

The conflict tore open sectarian and political rifts that had lingered since Lebanon’s independence from French rule, reviving an old question: Who should govern Lebanon? In a nation defined by its diversity, and made even more complex by the influx of Palestinian refugees following the Israeli occupation — that question became combustible.

What followed was a multi-layered war that drew in regional and international powers alike. In its wake came Syrian and Israeli invasions, the rise of Hezbollah, and a generation forced to come of age amid destruction, displacement, and the ruins of a fractured nation.

Through the Eyes of Patrick Baz

Amid the destruction, an 18-year-old Patrick Baz watched his country fall apart. He wasn’t a fighter, and he knew it. “I couldn’t carry a gun and fire at somebody,” he says. “I was bad at writing, the camera was my only means of expression.” So he took his father’s camera and began to wander through the ruins, taking pictures of things he didn’t yet understand. “I didn’t know how to use it. I was discovering,” he says. “You’d shoot one photo, then maybe wait a week to afford the next roll of film. Sometimes it took months before I saw what I’d actually photographed.”

Over time, those fragments he captured — the fleeting moments, the people caught between survival and exhaustion, turned into a kind of visual diary of the war. Each photograph carried a memory, a small piece of what he had lived through. “People always ask me to talk about my photos,” he says. “But I can’t. My photos are meant for others. What I can talk about is what happened.. what I saw, what the people I photographed went through.”

Looking back, Baz recalls moments that seemed to suspend time — when violence briefly gave way to something human, fragile, even absurd. We spoke to him to revisit these moments through his photographs, not for the bullets and bloodshed, but for the quiet, everyday stories that wars tend to erase — the ones people assume never happened, shaped by that cinematic stereotype that war is only rubble and silence, where daily life and human connection simply cease to exist.

What truly fascinated us as the interview went on was how Baz, while walking us through his photographs, recalled each one in astonishing detail: the exact date, time, place, the surroundings, the faces.. sometimes even the names. It was as if he hadn’t only captured the moment through his camera, but through his own memory as well, keeping it alive — in print and in thought.

L’Orchestre d’Arcy (1983), Beirut One of those moments came in 1983, when a French orchestra called L’Orchestre d’Arcy arrived in Lebanon to perform a classical concert. “A very close friend of mine, Philippe Aractinji — a film director — told me, ‘I’ll make them shoot a video clip, Ala Khotoot Al Tamas, so come and take photographs if you want.’ And they actually stopped fire to let us shoot,” Patrick recalls. “We were filming on the Christian side, in East Beirut.”

A displaced villager (1983), North of Lebanon

Another photograph Baz recalls — one that captured the “ordinary” victims of the conflict — was taken in ’83. It shows a displaced Christian villager who had fled his home, sitting quietly with a World War II rifle. “That was during the fighting between Druze and Christian forces in the mountains,” Patrick says. “I think I just snapped the photo while on my way to somewhere else. Maybe to photograph displaced women and children in a nearby shelter. But he caught my attention. There was something about him, sitting there alone with that old rifle. He had this calm that said everything.”

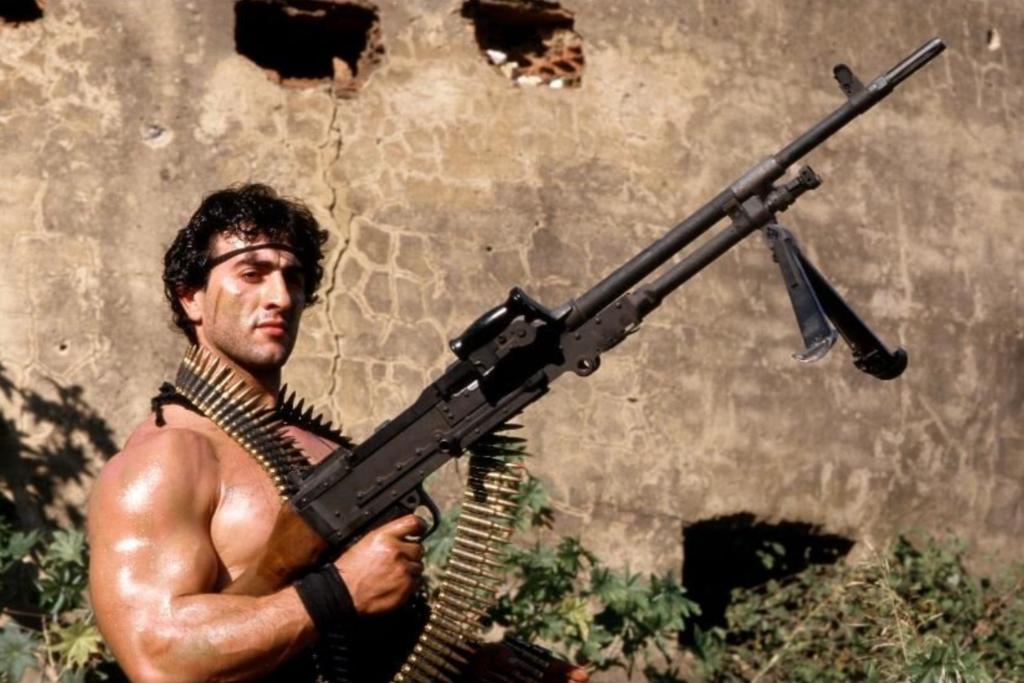

Missak Donanian or Lebanese Rambo (1987) – Beirut Then there was Missak Donanian, a fighter nicknamed Rambo for his uncanny resemblance to the movie character. “He was an Armenian member of the Christian Lebanese Forces,” Patrick remembers. “It was during the period when the Rambo series was being released. He was called Rambo for real because he was actually fighting, while Rambo was just a cinematic figure. Back then, media circles were very small, maybe a dozen people working for international outlets and when you heard of a story like that, it spread fast. He ended up becoming famous.”

Female members of the Christian Kataeb party parade (1984) – Beirut

His lens also captured a group of women parading in uniform — an uncommon sight on battlefields of that time and place — members of a Christian Lebanese militia. “They wanted to show that they had female fighters,” Patrick explains. “And they did. They weren’t just medics or nurses; they were actually fighting.” Since that photo was taken in 1984, Baz notes, “these were among the only female fighters left on the ground by then — the leftist Palestinian forces had already withdrawn from Lebanon after the Israeli invasion in 1982.”

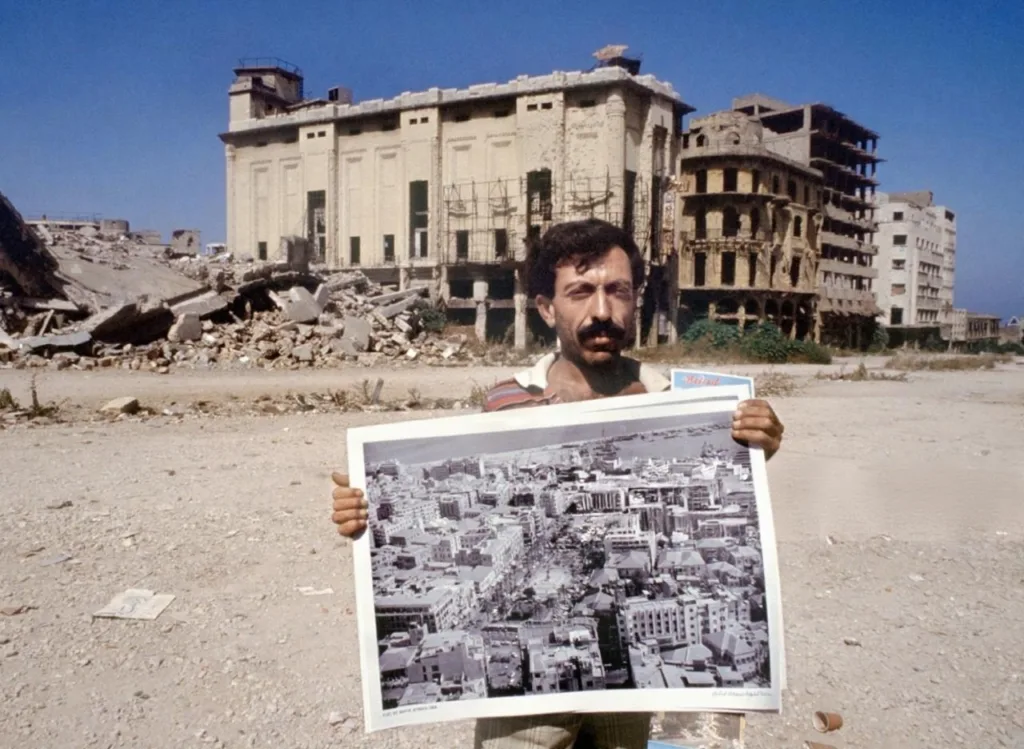

A street vendor in Downtown (1990) – Beirut

“Taken in 1990 — the year of the ‘end’ of the war and the physical dismantling of the Green Line and the barricades separating East and West Beirut,” Baz said, “it shows a street vendor selling a poster, in the rubble of downtown Beirut, of what the capital looked like before the war.”

Reflecting on the image, he added, “It’s a fascination for the Lebanese to always try to remember what the city looked like during its âge d’or.” This photo not only shows what the war had done, but also reflects an emotional state of longing for the past, for what could have been avoided but wasn’t, and for a nostalgia that will haunt the people of the city for God knows how long.

A Lebanese army soldier in front of a damaged building (2008) – Beirut

“Years later, the war still didn’t feel over,” Baz said. “Its aftermath was everywhere — in sight and in memory.” He recalled one photograph in particular, taken nearly two decades after the conflict. “It was May 14, 2008 — a Lebanese army soldier standing before a building still scarred by the civil war, with a flag of the Shiite Amal movement fluttering over its deserted entrance in Beirut,” he said. “Peace was signed on paper, and the fire had ceased, but the country was still in silent confrontation with its past.”

He added context to that moment: “Just a week earlier, on May 7, 2008, Hezbollah gunmen had clashed with Sunni Future Movement militants and taken over West Beirut. A dozen people were killed and a hundred injured.”

Frontlines. Aftermath. Reflection.

And beyond the photographs, since capturing the mayhem wasn’t everything, and after three decades on the frontlines with his vest, helmet and camera, Baz reached a breaking point. Wars had taken their toll. Not through a single moment, but through years of accumulated exhaustion from covering conflict after conflict. “I reached a point where I couldn’t walk, sleep, move,” he said. “I had nightmares, physical pain then I realized PTSD hit me.” In therapy, he began to understand that what had once given him purpose was now consuming him. “I was flirting with death for thirty years. We became friends. It didn’t take me, we didn’t get married, and I’m still alive.”

With time, his view of his own work also shifted. He began to question the weight people gave to photographs or maybe the weight he once gave them himself. “You get your photo published, and the next day they wrap fish and manakeesh in the newspaper,” he said. “Let’s face it, what’s the importance of these photographs?” It was a realization that didn’t come with bitterness, just clarity, that, for him, it was in the end.. just paper.

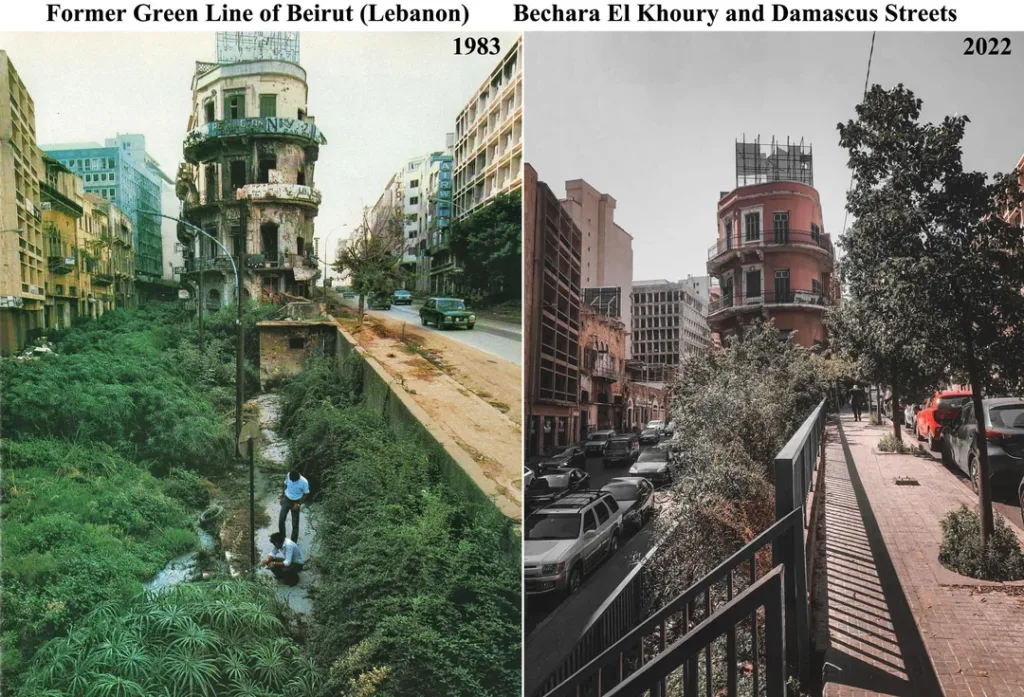

Even today, in his constant stream of reflections, Baz still feels the invisible fault lines that divide Beirut. “There’s an invisible demarcation line that’s still there, still splitting the city,” he said. “It’s not because there are no barricades anymore that the war is over. You can still see the roadblocks on the side, ready to be closed. Because simply, the war isn’t over — it’s just on pause.”

For Baz, the war never really ended, it just went quiet. “It’s on pause, of course it’s on pause,” he said. “The ones who started it, except the Palestinian organizations, are still there. Some of them even keep threatening to start it again — it’s part of their daily speech.” To him, the absence of reconciliation means the wounds never closed. “Who stood trial for the Lebanese Civil War? Almost none. Everybody is still free. The country is not a country, as Ziad Rahbani once said. it’s nations sharing the same geography.”

The Lebanese Civil War was never a conflict that could be reduced to simple equations.. It was, arguably, one of the most complex conflicts in the region’s history. Rooted in Lebanon’s deep diversity and shaped by the lingering curse of colonialism, its layers are still being unpacked today. Decades later, many of its scars remain visible — in politics, in society, even in what Patrick Baz once called the “daily trading, buy-and-sell life.” One can only hope that a time will come when the war exists solely in memory — distant enough to make relating to it a challenge.