Text Darío Karim Pomar Azar

We are nearing two years of genocide in Gaza. Those of us who have not turned a blind eye watch as incendiary bombs continue to rain down on Gaza, as tents for the thrice-displaced Palestinians are set ablaze, and zionism’s true purpose is laid bare for the world to see. We know – it has been livestreamed and made undeniably clear – that this imperialist project is predicated on the dispossession, erasure and, in its advanced stages, the genocide of Palestinian people, as well as the systemic targeting of all life-sustaining infrastructure in Gaza.

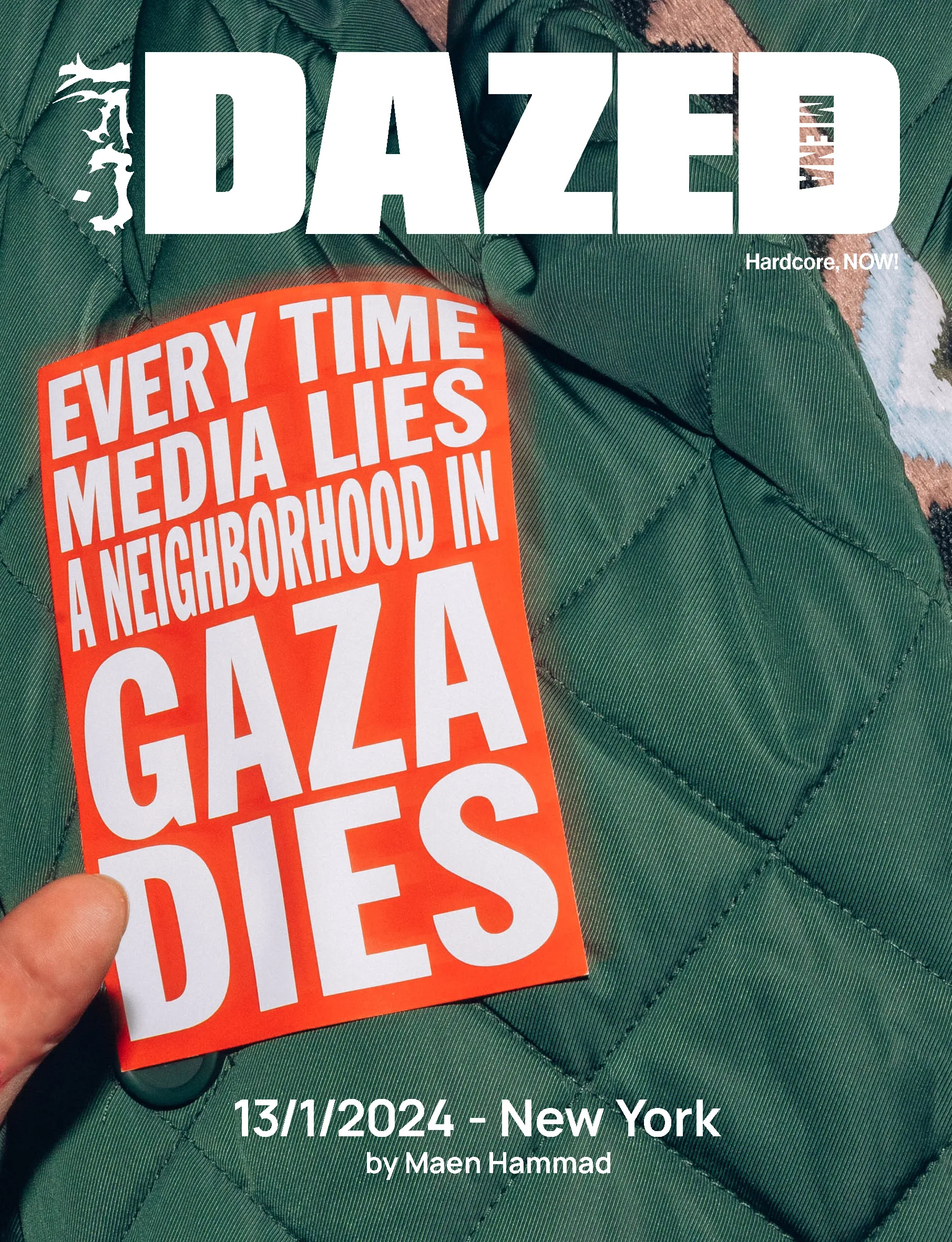

At the same time, as journalists in Gaza continue to be targeted and killed by the hundreds, we come closer and closer to a de facto media blackout: who will deliver us news from the source? Who will record and gather evidence of Palestinian life, resistance, and martyrdom? As Israeli forces expand their ground invasion of Gaza City, who will act as our eyes and ears? What unspeakable horrors might go unrecorded, and how will we be able to bring these to justice?

By strategically targeting Palestinian journalists, Israel aims to cull the very seeds necessary to raise the political consciousness of the global citizenry—who, upon witnessing genocidal violence and understanding how their own lives are intimately tied to it, are ostensibly compelled to act, to put an end to the genocide by making any support for it untenable.

Of course, we know that Israel heavily relies upon its ability to obfuscate and deny its own violence, to doubly erase Palestinians as well as any memory or trace of their erasure. If there is no record of the genocide, did it even happen? Or to put it more crudely: if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

And yet, we must look towards what we already have in our toolbox. For one, we have ample evidence of israel crimes. We have also inherited over a century’s worth of Palestinian resistance and knowledge, and a legacy of Palestinian steadfastness and sacrifice. Furthermore, while many across the world remain apathetic or cowed by fear – too atomised to see benefit in collectivity, too downtrodden by capitalism’s burdens, or too propagandised by zionism’s ideological battle – we would do a disservice to our movement if we didn’t also acknowledge the millions around the world activated by Palestine.

Over the last two years, many of us have had our consciousness raised by the Palestinians on the ground in Gaza and the West Bank, as well as by committed organisers worldwide who understand the importance of building a mass base of support for Palestinian liberation. These millions have come together in a deafening roar to amplify Gaza’s stifled voice. In turn, as history has often shown us, the more we organise, the more we must anticipate increased repression as a panicked response by imperial powers seeking to undermine a movement that is undoubtedly growing stronger.

The student front of this movement has played a central role in raising the political ceiling for the rest of us, spotlighting the struggle against carceral and institutional repression. It was the small hours of the morning on 17 April 2024, when students at Columbia University established the first Gaza Solidarity Encampment, a tactical response that was taken up by hundreds of groups across the world. Be it the Humboldt University in Berlin, the Institute of Political Studies in Paris, or Monash University in Melbourne, student protestors were met with clashes and crackdowns of an alarmingly violent nature. Authorities in the US and Europe have even exhibited techniques used by the IOF in Palestine—Dutch riot police used a bulldozer to dismantle an encampment at the University of Amsterdam before detaining 169 people. Many students have since experienced institutional retribution, suspended or expelled or stripped of visas for their involvement.

Alongside these more immediate and overt tactics of repression is a more implicit, albeit pervasive form of control: the suppression of transformative thought through imperial and elitist learning structures, typical of the western university model. Discussing the student-led fight against the University of California’s investments in South Africa’s apartheid regime in the 1980s, organiser Merle Woo articulated with forceful clarity the institution’s tactics in pacifying students and turning them into the model – defanged – citizen:

“Keep young people down, ignorant, destabilised,” she wrote in Three Decades of Class Struggle on Campus: A Personal History. “Make them compete for every good grade they get. Students have no economic power, so their survival depends on grades. Not knowledge, or maturity or integrity. Academic life depends on grades and degrees, and the false promise of a good job in the future. Turn them into arrogant snobs, ashamed of their immigrant or poverty-stricken, ‘uneducated’ ancestors.”

Indeed, by recognising universities as tools of empire, and students as their intended functionaries, encampments served to disturb the veneer of academic noblesse oblige and made business-as-usual implausible. They must be remembered as vehicles for radical politicisation that fundamentally transformed a generation of students and unsettled the relationship between them and their academic institutions. Importantly, however, most encampments did not achieve their primary goal of institutional divestment from zionist occupation. Although many student formations maintained Palestinian liberation and anti-imperial politics at the core of their struggle, tactical and strategic shortcomings reveal the movement’s political immaturity.

Now, over a year after the first encampments, we are reckoning with a markedly different political moment, one that requires critical reflection on the mistakes made and the lessons learned. Students globally are beginning to invest in long-term strategising, guided as ever by the Palestinian principles of Al-Thawabet and the material liberation of Palestine whilst being cognisant of what, and how long, it will take to do so.

Palestinian liberationists have long understood the Palestinian struggle as a protracted one. Accordingly, the student movement must build organisational infrastructure that can take it beyond an over-reliance on any singular tactic. A clear structure – where the leadership is empowered to develop strategy, unite members around it, build up other leaders, and provide direction for the group – is crucial.

An intentional approach towards handing over institutional knowledge to the next cohort of student organisers is also incredibly important. The student movement must steel itself against the instability caused by high student turnover and encourage outgoing student organisers to remain in dialogue with those they are passing the torch to. Indeed, individual organisers must act in service of something that is larger than themselves, identifying the steps they must take in order to fortify the organisation they are part of so that it can survive the comings and goings of any particular generation of students.

Furthermore, students must be in tune with the wider movement and take cues from adjacent labour struggles and emergent arms embargo campaigns. This way, students will learn how to develop multitactical approaches to building coalitional power on campus and beyond. They must articulate a proper theory of change: If we understand mass power as necessary to mount an effective campaign against our complicit institutions, we must think about how to best build this power.

For example, students should learn to meet prospective organisers where they are – politically or ideologically – and develop programming that appeals to a broad base of people and responds to their needs. Simultaneously, the student organisation’s projects, campaigns, and movement culture should shape these members into engaged participants who are ultimately united in addressing these fundamental questions of justice. Additionally, by dialoguing with established movement organisations, students have much to learn about identifying strategic targets and building effective campaigns around them, outlining achievable steps and amassing power along the way.

Ultimately, with Gaza as our compass, all fronts of our movement – including the students – will be able to better respond to the urgency of this political moment. We mustn’t despair at our unpreparedness or the inadequacy of our mobilisations and responses to mass starvation and the massacring of our people. Instead, we must take a step back and consider what we can learn from our past to understand what we must do now to accumulate power over time and achieve our goals of successfully confronting zionism and achieving liberation in the future. And students are undoubtedly a key piece of this puzzle.

.