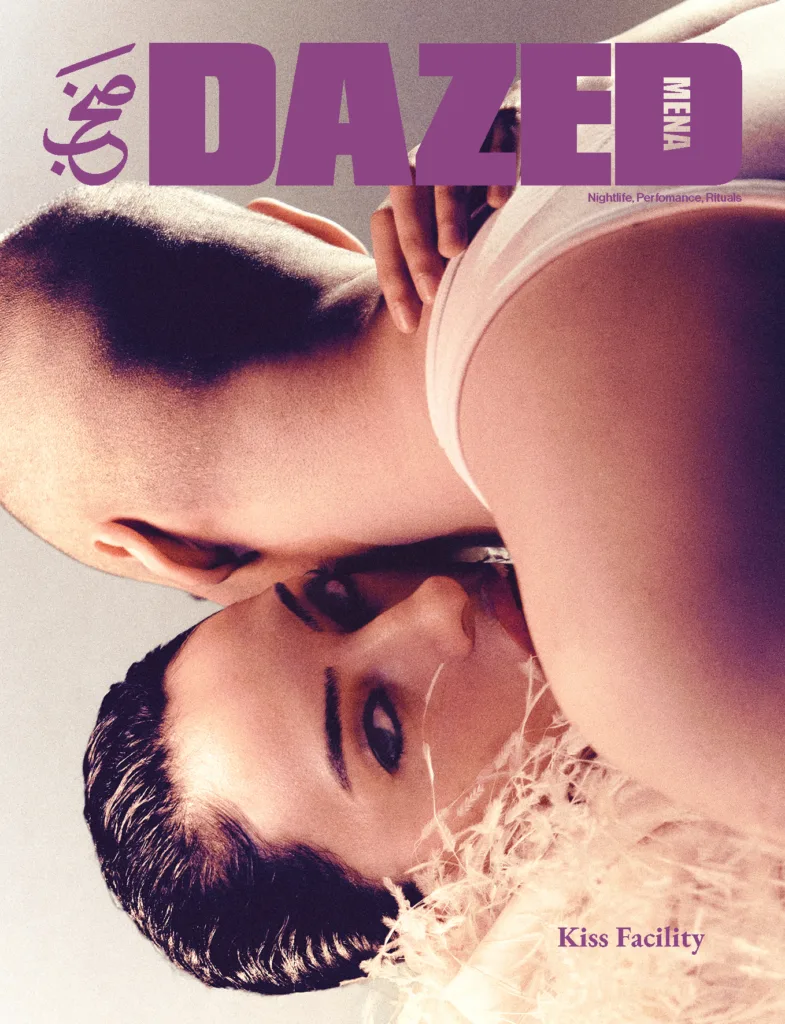

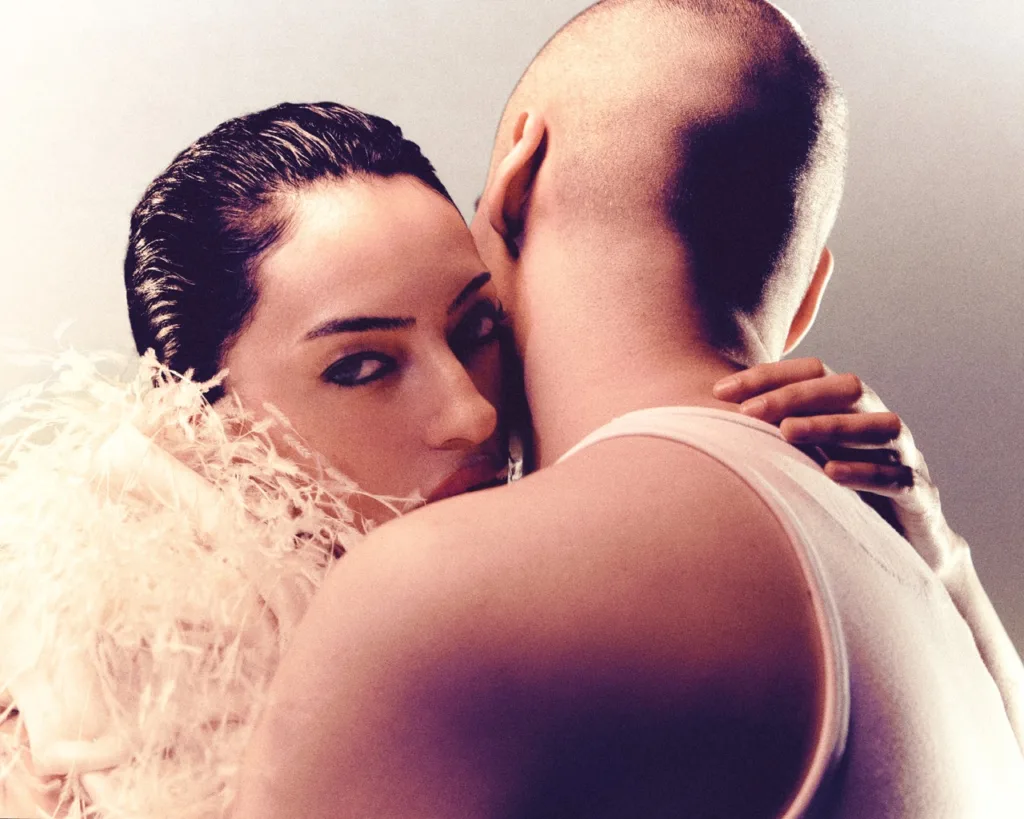

Text Sarra Alayyan| Photography Ibrahim Elhinaid | Styling Elena Mottola

Joining our 3pm video call from their apartment in Paris, Mayah Alkhateri and Salvador Navarrete (also known as Sega Bodega, although he prefers Salv) are just starting their day. “We sleep really late,” he says.

“Yeah, we sleep at 6am,” she adds, nodding as their cat Bug weaves between their laps. “Salv wakes up at noon, I wake up at 1pm. It’s kind of a really bad sleeping pattern, but we work that way. We also get everything done, so it’s not a bad thing.” It doesn’t come as too much of a surprise as we settle into our conversation—it starts to feel as though we’re speaking in a dimly lit afters, where deep reflection can find odd pockets of resonance and thoughts stunted by daylight’s caution are finally allowed room to breathe.

Originally published in Dazed MENA Issue 02| Order Here

Admittedly, the couple, collectively known as musical duo Kiss Facility, doesn’t need stimuli or a particular time of day for introspection and candour. They quite literally woke up this way. Coming from disparate backgrounds (Alkhateri is Emirati-Egyptian, Navarrete is Irish-Chilean), their lore began in the DMs back in 2022. “My friend, Omar Sha3, and I always share music, and one of the songs he sent me was a Sega Bodega track—it was unlike anything I’d heard before,” recalls Alkhateri. “I got so excited about it that I found his Instagram account and shared the song, and then we linked up. We spoke for a year, but never met. We were just online friends. After that, I got a job in London, where we finally connected.”

Their professional courtship happened just as organically. “I asked you to sing something into your phone so I could make something with it,” Navarrete reminisces, facing Alkhateri lovingly. “The first thing she sang on the voice note became the very first part of our first song, ‘In My Room’. And I was like, ‘Oh, that was easy. I like this.’” Kiss Facility, however, came with one condition, as he explains. “I just loved her voice so much. And I was just kind of like, ‘I’ll make stuff with you, but you can never sing in English.’”

Mayah wears leather shirt JIL SANDER

Much to our benefit, Alkhateri was on board. As the pair rightly asserts, the last thing the world needs is another Arabic singer shunning the melodic language for an alien English tongue. “I’m glad we agreed because I don’t think there should be more Arabic artists singing in English. We should embrace our language. We need more Arabic music, especially in other genres like alternative rock,” she says.

Their subgenre of choice, shoegaze, in particular, remains a largely unexplored landscape for Arabic musicians. “I was looking for Arabic shoegaze artists, and couldn’t find any,” explains Alkhateri. “I only found one Iraqi artist named Nabeel. What’s funny is that he released his single a day before we dropped ‘Black Stone’. It was such a coincidence!”

After its golden age in the 90s, pioneered by My Bloody Valentine, the British-born subgenre faded into relative obscurity with the onslaught of the 2000s, driving converts to more commercially viable pop sounds. Analogous to the broader global industry, regional gatekeepers tended to neglect the genre’s potential as a ‘hard sell’ or ‘too niche to succeed’, making representation scant. Despite the freak timing, however, the chance of two Arabic shoegaze singers cropping up in the same year isn’t so surprising.

The subgenre itself emerged from a highly experimental era in rock music at the time, when musicians sought new, radical forms and a desire to remain free from constraints—the Cold War had just ended, and the USSR had collapsed. With capitalism proclaiming victory, Reagan/Thatcher’s neoliberal revolution pillaged welfare and social safety nets with the heavy hand of mass privatisation and deregulation, concentrating wealth to a third degree, particularly within tech companies. Sound familiar?

Fast forward to today, the subgenre’s steady rise on TikTok as of 2023 is eerily prophetic, a recession indicator back from the dead, haunting us in temporal suspension. Around the world, artists are flocking to shoegaze, followed by listeners who crave refuge and rejection from the widening, desolate expanse of technocapitalism’s suffocating grip and the world’s rapid deterioration into despotic ethno-fascism. As they did 30 years ago, punk and shoegaze have been resurrected in reaction to these conditions.

The former, an abrasive middle finger to the establishment, was a treatise on nihilism, countering Fukuyama’s end of history with a shriek to Fischer’s cancellation of the future. The latter, however, retreats into fantasy—a melancholic, angsty reaction to the numbness of alienation and a capitalist totality. As a sound, its amorphous dreaminess offers refuge and escape. It’s also the beating heart of this duo, starting with its stage name. “Kiss Facility: a facility that people return to when they need an accompanying, loving person,” explains Alkhateri.

Far from apolitical, both Alkhateri and Navarrete bring the credence of their generation’s disaffected ennui to Kiss Facility’s sound. Navarrete’s discography, for example, undercuts a willowy cadence that’s woven throughout his work, including his production for others—Shygirl, Björk, Arca, Eartheater, and the late Sophie included. With an erudite talent for juxtaposing abrasive industrial sounds with softer, emotive melodies, his tracks often strike a strange lull between insufficient sleep and confusing wakefulness, hinting at a liminal unease. Although, as the world continues to glitch in the most violently unscrupulous ways, perhaps that is the most sane soundtrack we could hear circa now?

Talent and natural ingenuity aside, Navarrete’s upbringing in Glasgow played its part. There, he spent his formative years listening to an impressive range of sounds. “It was a range from The Black Dahlia Murder to Placebo, a lot of Warp Records stuff, and LuckyMe artists. My mum always showed me classical music, too,” he explains. As a teenager, meanwhile, he immersed himself in the city’s legendary nightlife scene, a hotbed for musical experimentation and part and parcel of regeneration’s effect taking hold for Glaswegian youth culture. “Glasgow is a very diverse and open-minded city. The clubs I was going to at 18, 19, 20 really embraced this idea that you can be anyone you want to be. You would have a real mixture of people, always,” he recalls.

Alkhateri, on the other hand, has a blistering lyricism that has made her introduction to the scene decisive. Throughout her songs, she navigates paradoxes of love, distance, abandonment, spiritual growth, sensuality, mysticism, loss and desire—the landscape covered by her breathy voice is sweeping. There’s an almost Odyssean quality to them, as if she undertakes some kind of journey each time, beginning with the first few lines she ever sang in her voice note to Navarrete:

I don’t know where I’m walking towards

Lost between two ribs

And I, the one who’s been absent for years have been living two lives inside one soul

This wandering, however, has a material truth to it. Growing up in Ras Al Khaimah, Alkhateri was under the care of her mother, who played the staple music diet of many Arab households – Abdel Halim Hafez, Fairuz, and Omm Kalthoum – on repeat until her passing. Suddenly, under the care of her family’s stricter side, a young Alkhateri was restricted to devotional music in the form of nasheeds—something she is now fond of.

After being forced to study chemical engineering at university, she escaped to Dubai, where she began dabbling in modelling and became more active on social media. “One of the main reasons we started Kiss Facility was that I ran away from my family,” she explains. “I know we don’t speak about it as much, but many of us have very toxic families. And our families don’t need to be our family if it gets to our mental health or freedom as a human being.”

It’s one of the harshest pills to swallow: familial love is not a given, nor are a family’s bonds sacrosanct, especially within oppressive contexts. “I just wanted this platform to show people like me that they can do whatever they want and be their own person. I know it’s very hard to start from zero and leave everything behind. But I want this platform to show them, Arab women in particular, that it’s possible.” The errantry in her sound, then, seems to be less of a restlessness and more of a healing force—especially directed towards women like her, those trying to unbind from sequestered notions of the self and reject inherited traumas passed down through generations.

Similarly, much of Navarrete’s work – irrespective of Kiss Facility – subliminally explores the fugue of standardised masculinity and inherited models of misogyny. “There is no truly open-minded type of man; they all try to project themselves into what they see around them, like my audience. They just assume I’m just like them and, for some reason, it rattles their brain when they find out I’m not,” he reflects. “I hope that they can see that there is no type of ‘man’ in my music. The reaction to someone who you think is one thing and they’re not that thing should be met with an embrace for the freedom of all types. I have to challenge my audience to do that, too, because there are a lot of expectations around what people are,” he explains. “I just try to be myself in the music and kind of hope people kind of get it.”

Kiss Facility’s soft melancholia, therefore, sharpens—Alkhateri’s voice and Navarrete’s melodies are sonic palliatives to generational trauma. Whether exploring the force of spiritual rebirth or the evil eye, each exudes a desire for somatic and ontological healing.

Mayah wears leather shirt JIL SANDER

It’s no surprise that Alkhateri’s first voice note felt so instinctive; she has spent her life immersed in sound and asserting her right to listen. “I used to run blogs we called montadayat,” she explains, speaking fondly about what digital access has provided her. “I wouldn’t have discovered Iranian, Albanian, or Turkish songs and all these crazy sounds that I like just listening to otherwise. It’s a nice tool to discover music.” She also cites the late Genesis P-Orridge as a constant creative and philosophical inspiration, drawn to their radical notions of freedom and transformation—a dynamism easily foretold through Kiss Facility’s sound.

On the other hand, despite having a meme account, which he started during the pandemic, Navarrete regards the internet as “a really dangerous place” that, beyond the effects of the algorithm on music, can land too many youth in perilous corners of gore. As for AI? He isn’t as bemused or apprehensive. To him, its use in the music industry is just the latest shortcut in a longstanding evolution from a pattern of labour extraction and precarious crediting. “There are always people who cut corners. Some of the biggest producers have the guy who’s actually making the beat, but then it’s branded to something else. That’s essentially like using an AI,” he points out.

All that said, Navarrete is not one to shy away from the internet. He’s actually one of the few artists adapting the rules of engagement between artist and fan base through it. A considerable chunk of his album Dennis came to life on Twitch, with Navarrete letting fans into his private rituals in Logic, a kind of performance where each track unfolded gradually under the watchful gaze of his online audience. In doing so, he finds a way to bypass, or outright reject, industry gatekeepers while retaining complete ownership over his sounds—a basic principle not readily afforded to most musicians.

Naturally, living by their word and internal shoegaze doctrine, both Navarrete and Alkhateri reject the industry’s doctored representations of their ‘ideals’. Whether it’s gender performativity, self-branding, or market packaging, they refuse to let their identities be taxonomical. It’s no wonder that both remain independent. Navarrete has even launched an independent record label, Ambient Tweets, a third space for peripheral artists who have been increasingly overlooked in an alienating era of streaming monopolies and recording giants usurping musicians’ livelihoods. “It’s been fun because I get to work with brand new people who don’t have any foundation or fan base. It’s rewarding to see them blossom and be able to help.”

“You’re very good at finding artists who have potential,” Alkhateri tells Navarrete, turning towards him glowingly. “I love all the songs you’ve been releasing as well. Every time I meet the artists, I think about how they deserve better than where they are now. It’s so nice because not many labels want to actually help artists; they want to take advantage of them. But you’re doing the complete opposite of that.”

For Alkhateri, who’s looking to focus more on solo projects, the industry can be disillusioning, particularly within the region. “I’ve worked with several agencies and managers, and been in meetings with so many people in the region. They always say one thing: ‘We love what you do, but can you tone it down with the clothes and stuff?’ But that shows they don’t want to work with me. It means they want to work with the person they’ve painted in their head,” she quips, rolling her eyes. The regional industry, as she highlights, has become increasingly fraught with identity politics.

It’s a domino effect from the wider ecosystem; while global artists are growing in popularity, they’re often asked to perform according to caricatures of their heritage and background. Their identity becomes a brand narrative fit for SEO-friendly headlines, verification ticks in the industry’s cultural image of how appropriately they fit in the ‘SWANA’ subsection of the ‘world music’ box.

Alkhateri, in particular, with her cybersigilism and gothic aesthetic, is a protruding outlier. It’s gotten her a fair share of backlash, which she explains is inflamed due to her background to a degree. But without falling into the clichéd trope of exceptionalism around Arab women, the trolling is part of a more systemic, universal problem of policing women’s bodies—one that Alkhateri has done much to fight. Refusing all attempts to pull an obedient performance out of her, she has never given in to anyone, and she won’t start now, no matter how big the label. “I’ve been who I am for my whole life,” she asserts. “This is what I’m trying to push for the people. I just want to do things my way.”

Beyond being a medium for self-reclamation, however, so much of Alkhateri’s music is tied to her regional homeland and springs from everything happening to the collective. “It’s about what ignites the music. For me, it’s all about rage and sadness and whatever is happening. It just makes me really mad, so we make Kiss Facility music, and I try as much as I can to turn the rage and sadness into hope because we don’t want sadness,” she says. “I want people to feel a sense of hope at the end of the day. We’re not weak people, we’re f*cking strong. And we want to show that part more than making all these westerners feel sorry for us.”

At a time when freedom is a flattened concept, increasingly out of reach, Alkhateri and Navarrete are compulsively searching for it, encouraging us to do the same. For all their dark inflexions, they’re light and welcoming, eager to share and feel embraced. And for all the longing and haunted love that lives in their music, Kiss Facility is more dexterous than the saccharine glow of optimism. It’s an offering, almost totemic, that opens up a space where emotional honesty and spiritual growth can take root in sound.

Originally published in Dazed MENA Issue 02| Order Here

Set designer CHRISTIAN FELTHAM, make-up artist MAELYS JALLALI, hair ALEXANDER SOLTERMANN, production ANGELS PRODUCTION, lighting assistants ANDREAS STRUNZ, ANDRÁS LADOCSI, DOP POLINA ZHUKOVA, stylist assistants TERRY LOSPALLUTO, LIVIA MARGHERITA LAI, SANYA BATRA, set design assistants TIAGO RUNKEL, DEA ARRIGHI, location MARIA STUDIO